Necklace with goat ornament and coin pendants c. late 19th century

0:00

0:00

silver, metal, sculpture

#

silver

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

islamic-art

Dimensions: 3/8 × 4 1/4 × 3 3/4 in. (0.95 × 10.8 × 9.53 cm) (ornament only)

Copyright: Public Domain

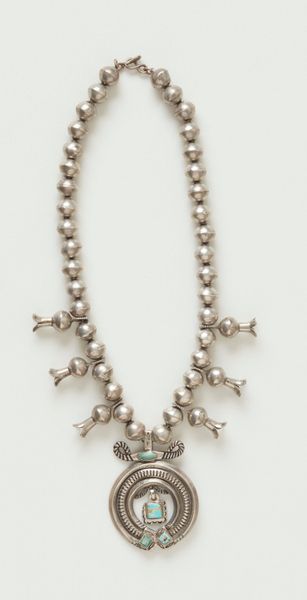

Curator: Let's take a look at this late 19th-century necklace made from silver and metal, currently residing here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It features a goat ornament along with coin pendants. Editor: At first glance, it gives me an impression of ritual adornment, of something precious and perhaps talismanic, the chain contrasting with the heavier ornament. What feeling does the piece evoke for you? Curator: I'm drawn to the layering of symbolic power here. The goat, an animal often associated with virility, strength and determination throughout multiple eras of culture, coupled with coin pendants suggestive of economic empowerment, is quite telling. Editor: Yes, the layering is significant. We have the intersection of wealth and what could be seen as a symbol of nature or the wild—in this case the animal could be related to pre-Islamic symbols. The coins may represent actual currency or stand for broader notions of trade and power. What social statements were common with these adornments? Curator: Well, ornaments of this style—made with silver, coins, and animalistic figures—were historically linked to both trade networks across Islamic communities and a reflection of socio-economic status within them. Think of the complex exchange of traditions across geographies, particularly through diasporic populations! It embodies not only prosperity, but also connection to communal history. Editor: Absolutely. Beyond individual expression, this necklace resonates with collective narratives, a form of silent storytelling. It presents us a lens through which we can consider how marginalized peoples utilized these tools to voice political beliefs in their resistance efforts. And considering the piece's cultural backdrop, what does its place within an institution mean? Curator: I think its inclusion here highlights the continuity of values across culture, demonstrating both material culture history while validating this powerful cultural presence. A reminder of resilience, displayed as adornment, now inspiring reflection. Editor: It also opens up crucial conversations about cultural sensitivity and ownership, acknowledging how contemporary museum settings interpret culturally specific adornments from an objective perspective. Well, on that note, it feels imperative to take a broader look. Curator: Precisely, placing art inside institutional narratives can become a conduit to understanding historical undercurrents through cultural preservation.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

More than one hundred years ago, the elite of the Danhomé Kingdom in West Africa would have worn these silver ornaments to adorn themselves and show off their wealth, and also to protect themselves from harm and evil. Fashioned by jewelers from imported silver coins, the ornaments were embellished with tiny sculptures that refer to past kings, heroic wars, and the Vodun religion. The coins attached to the ornaments date from between 1873 and 1910, bridging the last decades of the independent Kingdom and the first 15 years of French colonial rule.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.