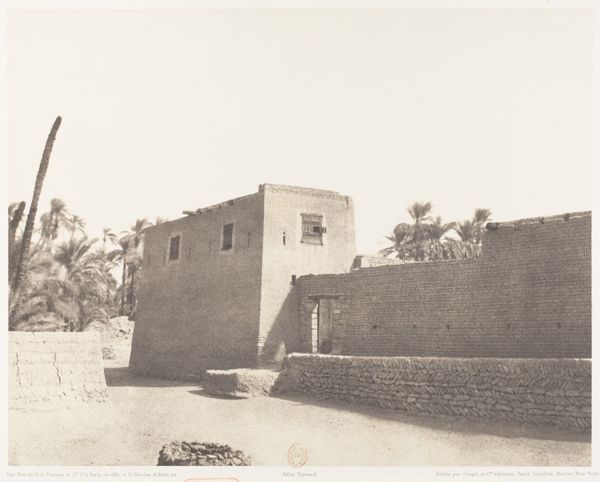

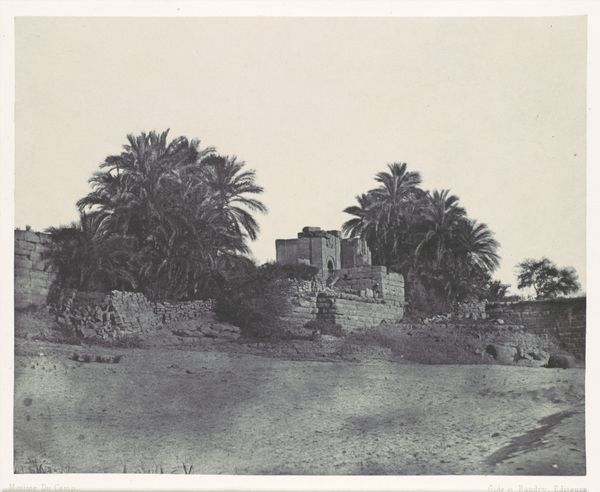

Syout, Habitations Arabes sur le Bord du Nil 1851 - 1852

0:00

0:00

photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

outdoor photography

#

photography

#

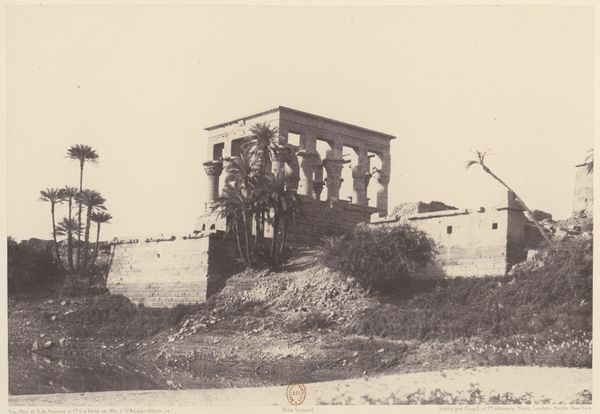

ancient-mediterranean

#

arch

#

cityscape

#

architecture

Dimensions: 23.9 x 30.0 cm. (9 7/16 x 11 13/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is Félix Teynard's "Syout, Habitations Arabes sur le Bord du Nil," taken between 1851 and 1852. It's a photograph, quite striking in its almost bleached-out quality. I’m intrigued by the sharp delineation between the architecture and the land. What strikes you most about it? Curator: For me, the beauty here lies in the evidence of its creation. Look at the process—the collodion process, likely—the glass plate negative, the material reality of 19th-century photography. It's not just a landscape; it's a document of labor, of chemical processes harnessed to capture a specific time and place. Notice how the light almost seems to flatten the image; how do you think that informs our understanding of this "landscape" as a manufactured representation, a product of material conditions? Editor: I see what you mean. It’s like the image itself is an artifact, not just a representation of one. Does the starkness—almost like a building site in some ways—relate to the social or economic conditions? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the colonial context. Teynard was part of a French scientific expedition. His photographs weren't just art; they were tools of documentation, feeding into a larger project of colonial knowledge production. The starkness reflects, in part, the power dynamics inherent in that gaze, reducing a lived-in space to an object of scientific study, measured through this new industrial means of photographic representation. It becomes less about artistic license and more about technical constraints imposed by the colonial machine. Editor: So, seeing it as a document of the photographic process and the social forces at play helps us understand it better. I never thought about it that way. Curator: Exactly. It prompts us to examine not just what's depicted, but *how* it was made and *why* it was made in the first place. By focusing on the materiality and the circumstances of production, we move beyond a purely aesthetic appreciation. Editor: I learned a lot by analyzing this piece through that lens, paying attention to how and why, instead of simply admiring what’s there. Curator: And that perspective offers a rich entry point into thinking critically about all forms of art, wouldn't you agree?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.