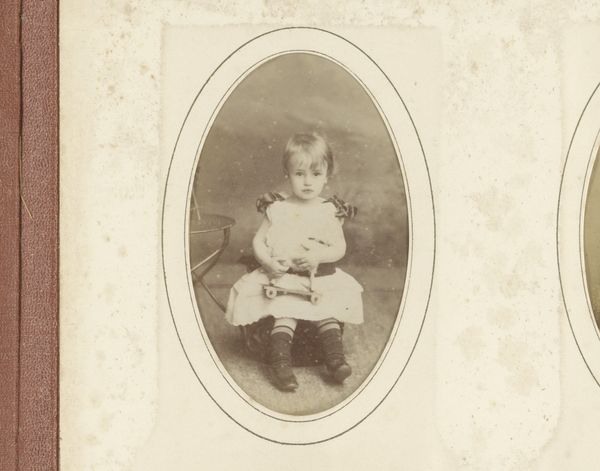

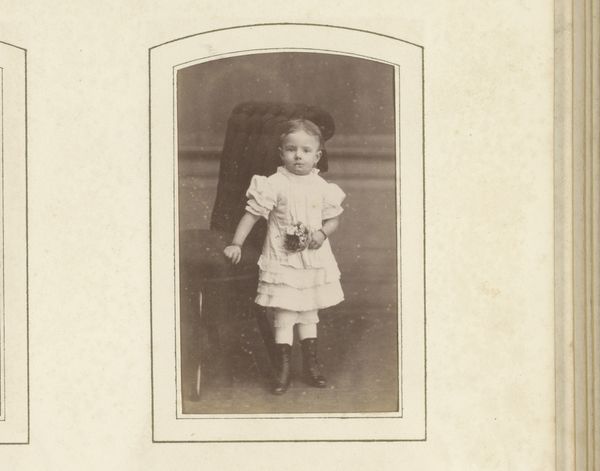

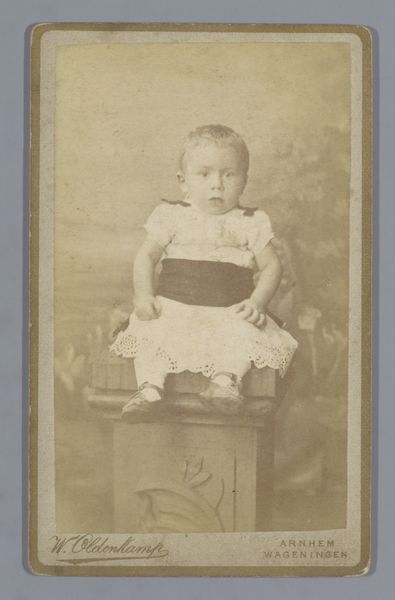

Portret van een meisje en een hond, zittend op een stoel 1874 - 1887

0:00

0:00

albertgreiner

Rijksmuseum

print, daguerreotype, photography

# print

#

dog

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Portret van een meisje en een hond, zittend op een stoel," or "Portrait of a Girl and a Dog, Sitting on a Chair" by Albert Greiner. It's a daguerreotype, a very early photographic print, dating from around 1874 to 1887. Editor: It’s interesting how this simple sepia-toned image manages to evoke a kind of Victorian seriousness—almost severity, even in the young girl's posture and the dog’s focused gaze. The whole thing reads as formal and a little intimidating. Curator: It is fascinating how posed and constructed early photography was! The trappings of realism don’t make it necessarily “real,” of course. Consider the class dimensions, for example. Photo studios would have been costly; so, instantly, it signals something about economic power. Also, note the little girl’s clothing, it speaks of the expectations placed upon her regarding behavior and gender. Editor: Exactly, these objects serve as visible markers of status. The chair is throne-like. I think this connects the child and dog with concepts like loyalty, duty, and perhaps even authority – symbols were integral for Victorian self-presentation. But is there also something more universal here, in a relationship between a girl and a dog? Curator: Possibly, but it's crucial not to strip the image of its historical specificity. To ignore the social constraints placed on women and girls would be a mistake. Even something as ostensibly benign as a pet was linked to complex ideas about domesticity and women's roles within the household. Editor: I appreciate that reminder. For me the photo sparks so many possible narratives, though – stories that span classes, genders, and cultures. Maybe it's naive to seek universality in a 19th century genre painting, but aren't core human experiences embedded within this photo, beyond the period and the style? The symbols of companionship, expectations and love… Curator: I can certainly see the pull of those potential narratives, yet to interpret those feelings without considering the social impositions the girl might have been subjected to will necessarily dilute any sense of social responsibility that this artwork could generate. Editor: Point taken! Perhaps understanding what we are bringing *to* the photo matters as much as what the photograph itself explicitly conveys. Curator: Indeed. This photograph helps us reflect both on history, and also on the ways in which we interpret that history through our current socio-political framework.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.