#

toned paper

#

sculpture

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal art

#

oil painting

#

earthy tone

#

underpainting

#

home decor

#

charcoal

#

watercolor

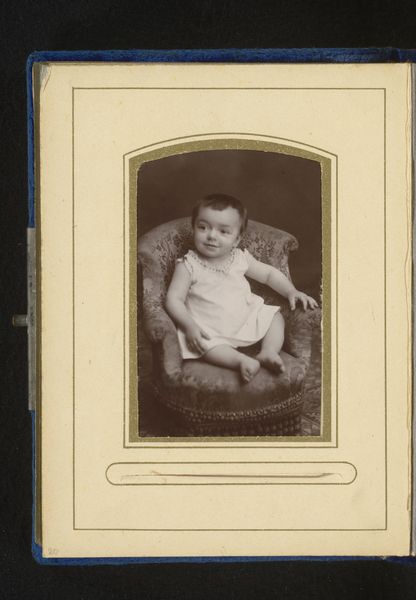

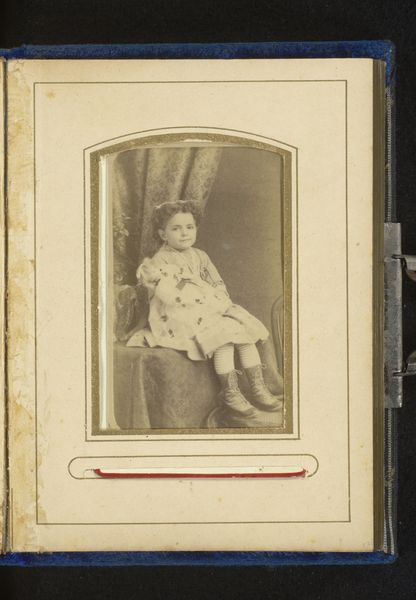

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 54 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

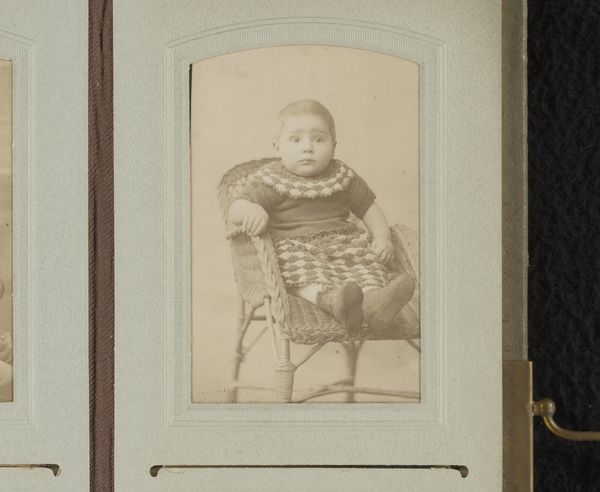

Curator: The work we're looking at is titled "Portret van een peuter op een stoel," dating from somewhere around 1890 to 1910. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is one of stillness, almost melancholic, despite it being a portrait of a child. The muted tones contribute to that, and the pose… a quiet solemnity. Curator: Portraits like this, particularly those of children, were often tools to project a certain image of respectability and social standing. The details – the wicker chair, the child's clothing – speak to middle-class aspirations and ideals of domesticity during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Editor: Absolutely, I agree, but let's think about childhood in that era. Innocence, yes, but also the strict gender roles being instilled even at this young age, those very ideals. I wonder, to what extent did this child's lived reality correspond with this carefully crafted representation? What pressures were at play to get them to pose in that way, to present an outward sign of the parent’s respectability? Curator: It is difficult to discern if this image upholds traditions of gender. What if we also consider the material limitations? As you mentioned, maintaining composure in front of a camera for an extended time would pose challenges for any toddler, adding another layer of constraint beyond imposed ideals. Editor: Precisely! The very act of creating this image was an exercise in power dynamics. It speaks volumes about how children were viewed and treated within the social structure of the time, and the very real pressures to perform within it. These issues are definitely worthy of being addressed when appreciating it! Curator: It certainly reveals the performative aspects of photography in that era and the sitter-photographer dynamic! Editor: Considering all this context, I'm now seeing this image not simply as a charming antique photograph but also as an open question about representation, power, and the silent narratives woven into our inherited histories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.