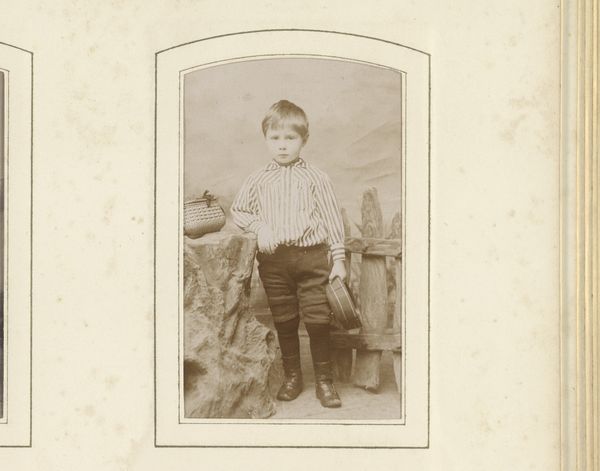

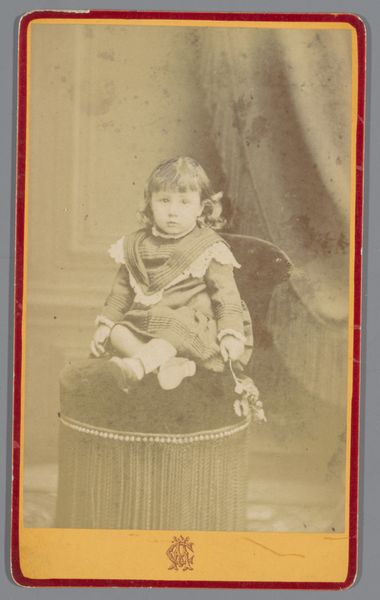

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So this is "Portret van een staande jongen met schep", Portrait of a standing boy with a shovel, created between 1887 and 1890, by Albert Greiner. It’s at the Rijksmuseum now. I’m immediately drawn to the tactile quality of the photograph itself; it's aged, but feels almost like a tangible object, rather than just an image. What jumps out at you about this portrait? Curator: The material process intrigues me. Look closely: the clothing, seemingly ordinary for its time, speaks volumes about textile production and the consumerism of childhood. Factory-produced fabrics versus perhaps hand-knitted elements? How does mass production begin to shape even personal identity at the end of the 19th century? What about the shovel; is that child labor or domestic labor on display here? Editor: I hadn’t considered the implications of the fabrics so directly. It’s interesting to think about mass production influencing individual portraiture. And I didn't initially focus on the shovel and how that might mean domestic duties or an economic need, now that feels extremely apparent! Curator: Consider the albumen print; the process itself allowed for reproducibility, pushing art photography towards a commodity form, away from unique hand-crafted prints. Note the studio backdrop; how much labor goes into creating the perfect context? Is it masking economic conditions, or mirroring the class aspirations of this sitter and his family? What is "authentic" in such constructed scenarios? Editor: It makes me think about how even early photography was performative, consciously created, never entirely documentary. Curator: Precisely. It makes you question not only the boy's lived experiences, but also those of the photographer, the studio assistants, the textile workers producing his garments. Photography in itself represents labor and commodification! Editor: Seeing it from a materialist perspective gives it a much richer and more complicated texture. Thank you! Curator: Likewise! The image now prompts entirely new ways of interpreting the context it emerged from.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.