photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

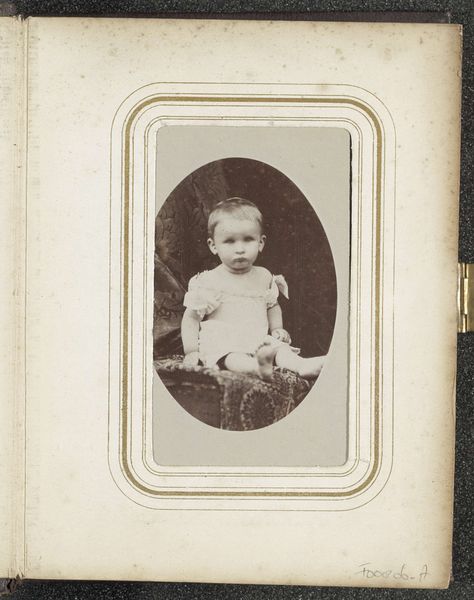

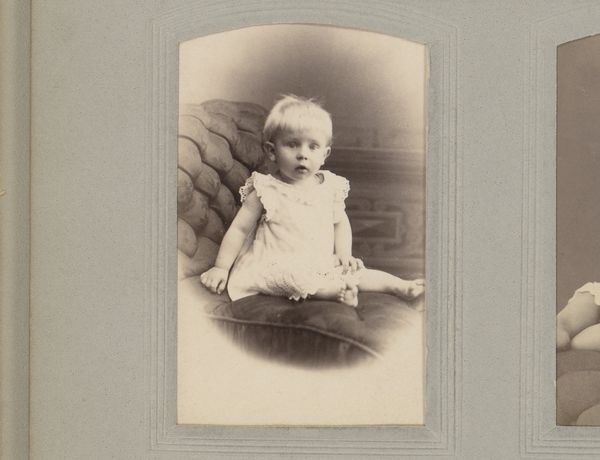

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

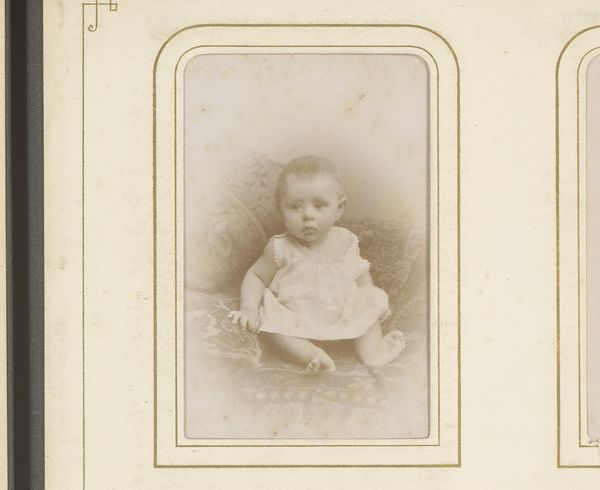

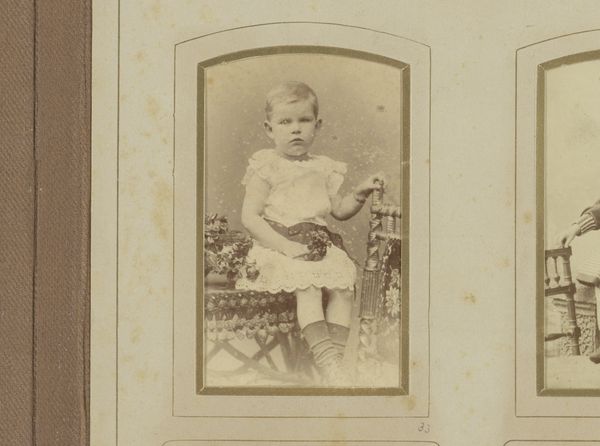

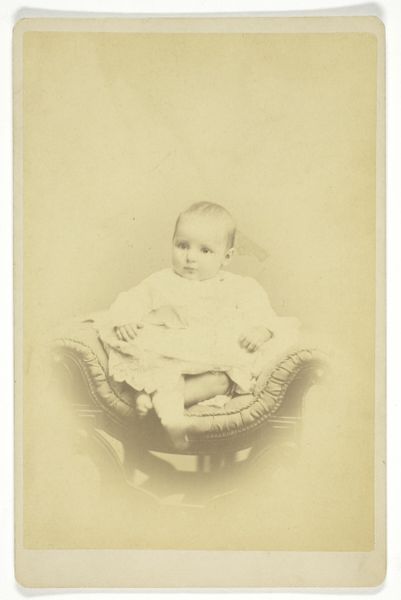

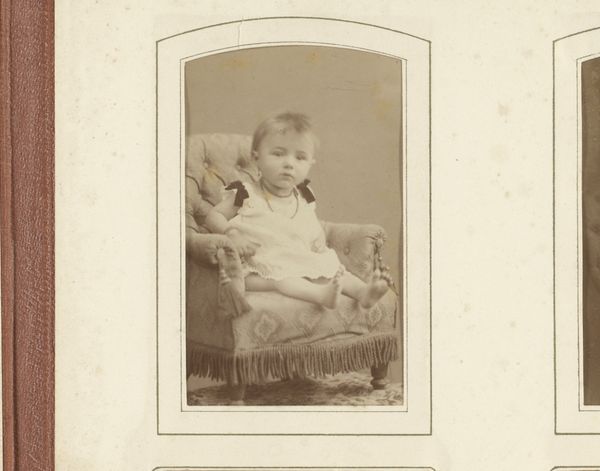

Curator: This is an albumen print dating from approximately 1870 to 1890, attributed to Woodbury & Page, entitled "Portret van een onbekende baby"—Portrait of an unknown baby. It's housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: What strikes me immediately is how staged and formalized this portrait is. Despite the soft focus of the sepia tones, there’s a certain weight, a gravitas that we don't typically associate with images of infants today. Curator: Indeed. We must consider the colonial context in which Woodbury & Page were operating in Indonesia. Photography was becoming more accessible, but it still carried a certain weight of social importance and performativity. A studio portrait would have signified a degree of status. Editor: And the very iconography of the baby enthroned, you might say, on that tufted armchair suggests an inherent value. Consider how frequently chairs appear as symbols of power, lineage, and legacy throughout art history and different cultures. Even an unknown baby warrants an elaborately decorated seat. Curator: Absolutely, it begs the question of how we value human life differently across race, class, and national boundaries then, and now. Photography from this era raises critical issues related to colonialism and representation. How often are portraits of the colonized subjects staged, posed and then framed according to the cultural lens and economic gains of the colonizer? Editor: You’re right; while on the surface this may seem like a simple sentimental portrait, its deeper symbolic roots lead to a complex and difficult lineage. Even the very pose of the child - facing squarely towards the viewer with unflinching eye contact - mimics earlier portraits of royalty. Curator: And the use of soft lighting in early photography tended to idealize and render the sitters in the way the photographers wanted them seen. Who was this baby? Whose gaze truly matters here—the photographers', the patron commissioning the artwork, or someone else entirely? Editor: Thinking about visual symbols opens avenues to questioning those very power structures. While we’ve speculated about this portrait's iconography and how it intersects with identity and power, we must also continue our work exploring the untold histories. Curator: Agreed, delving into the historical, political, and economic influences surrounding it allows for critical reflection. There is more than meets the eye.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.