carving, bronze, public-art, sculpture

#

public art

#

statue

#

carving

#

classical-realism

#

bronze

#

public-art

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

urban life

#

urban art

#

street photography

#

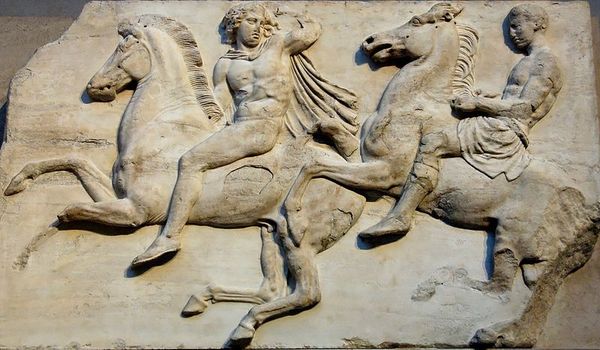

mythology

Copyright: Public domain

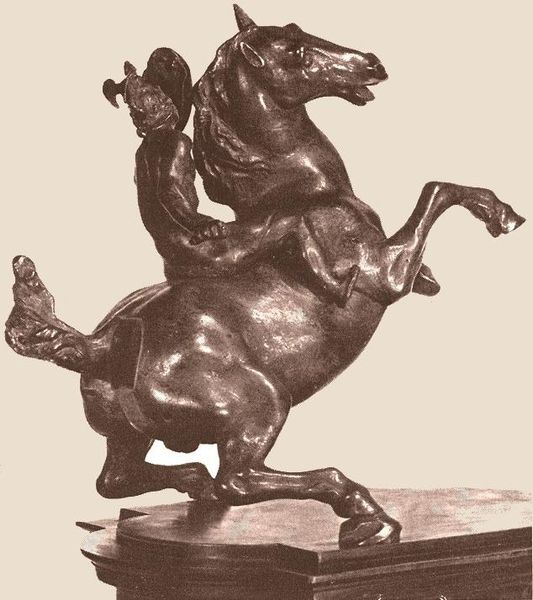

Curator: Right, let's talk about this piece. What strikes you first about Ludwig Manzel's "Europa" from 1913? Editor: It looks surprisingly... complacently powerful? Europa reclines on the bull almost casually, there’s no sense of struggle or distress, even though the myth involves abduction and potential violence. The material looks like it might be bronze, a hard material to create the sensation of smooth flesh and soft robes. Curator: Exactly! The use of bronze and carving elevates what could be a simple mythological depiction into a study of power dynamics in early 20th-century German society. Manzel, a well-regarded public artist of his time, frequently contributed sculptures celebrating national identity, and often worked for royalty, thus contributing to maintaining the traditional canon. Editor: So, how does presenting the tale this way play into German identity at the time? A powerful woman seemingly in control of her own destiny, rather than a victim, becomes a figure of national strength, maybe? This kind of artistic decision certainly has implications about idealizing strength over consent. Curator: Absolutely. Keep in mind that the traditional interpretation often glosses over the violence. It's about destiny, a new world being born – themes very popular at the time with imperial powers wanting to showcase their power and cultural dominance. The artist gives you a classical composition, a mythological subject... Editor: ...and wraps it up in the visual language of empire. By domesticating Europa’s terror and asserting control, the artist could subtly reinforce power narratives for the viewing public. Curator: Precisely. Consider how public art like this helps shape the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. Manzel here almost asks us to celebrate, or at least accept, these traditional power structures as if divinely ordained. Editor: It does bring up the question of who is the audience meant to be with works like this. What did different demographics in German society during the early 20th century make of an artwork such as "Europa", in this configuration, with a specific goal to glorify traditional power dynamics? Curator: Food for thought! I guess thinking about it this way gives me an interesting fresh perspective. It all comes back to this idea of public art not simply reflecting society, but also playing a role in actively shaping it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.