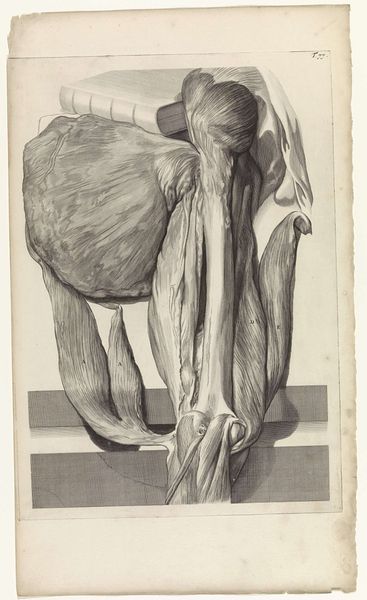

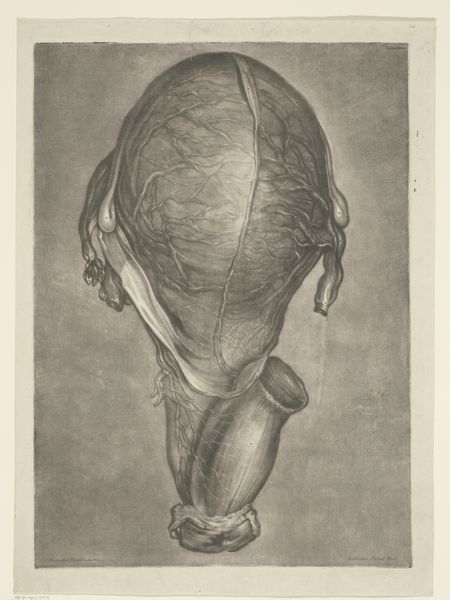

drawing, ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen illustration

#

figuration

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 20 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

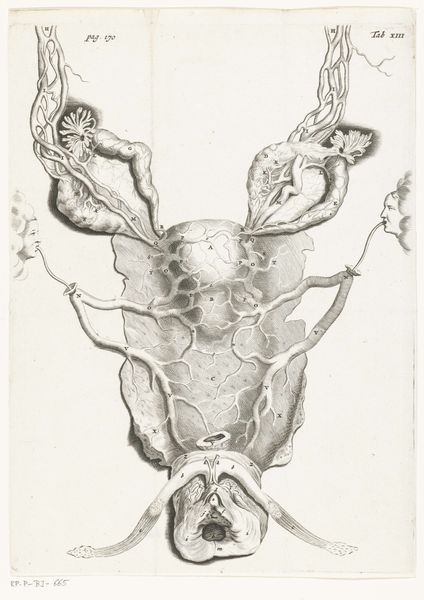

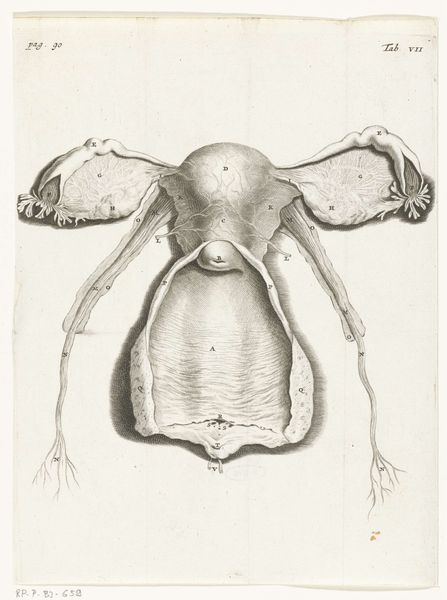

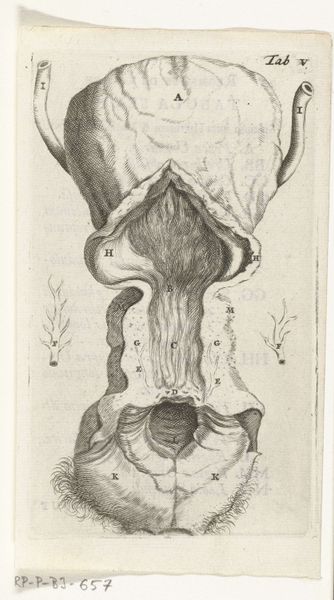

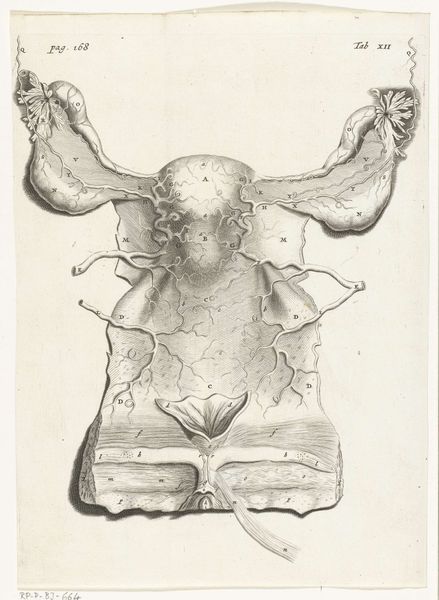

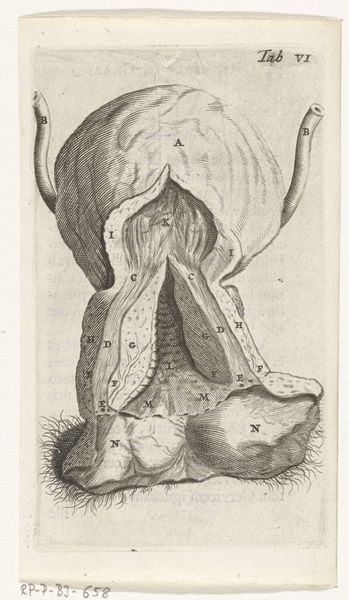

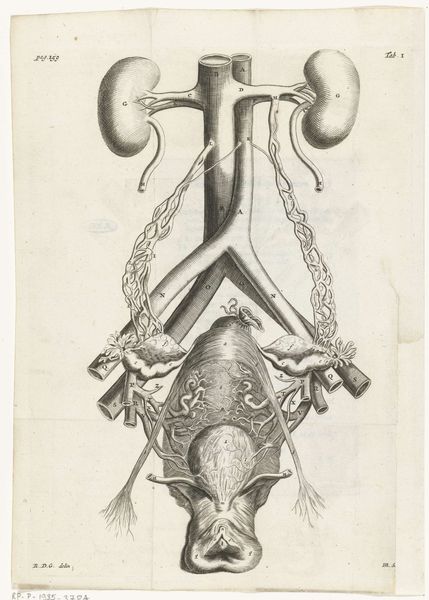

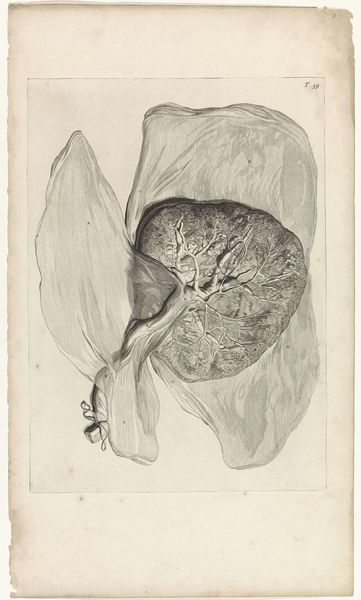

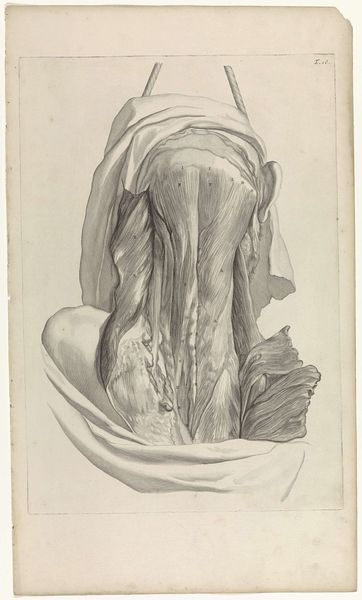

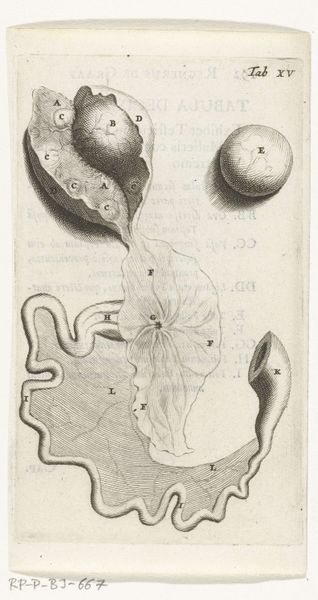

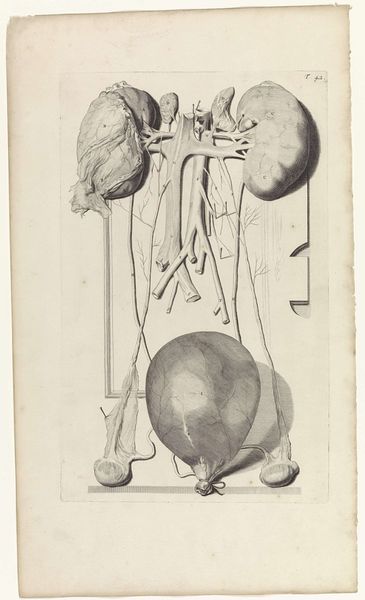

Editor: Here we have Hendrik Bary's "Anatomical Illustration of the female genitalia," made with ink, pen, and engraving in 1672. It is unbelievably detailed. How do you read an image like this within the context of its time? Curator: It is certainly confronting to contemporary viewers. Images such as these circulated amongst medical communities and were directly tied to the advancement of scientific understanding, but what does it mean to make visible something previously hidden and associated with the feminine? In its time, this precise and public rendering reinforced emerging scientific authority, and reshaped how society literally viewed the body. Editor: So, the act of representing itself is a power dynamic? Curator: Precisely. Who gets to represent whom, and for what purpose? Consider the art world’s existing bias towards male representation – was the depiction of female anatomy an attempt to correct, or to further inscribe a patriarchal viewpoint on the female body? Also, to whom was this image addressed? Editor: I imagine not the average person! Maybe this piece normalized a male, scientific gaze, solidifying medicine's power? Curator: Exactly. Medical imagery helped construct a very specific relationship between doctor and patient, knowledge and power. Bary's meticulous style lends legitimacy and, importantly, claims objectivity to the process. It invites the viewer into the domain of science, shaping perceptions that persist to this day. Editor: That's incredibly powerful – to realize that this isn't just about science, but also about the social construction of knowledge. Curator: Indeed. Seeing art as a participant in socio-political discourse, helps us better appreciate both its history and its continued relevance.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

In 1672, physician and anatomist Reinier de Graaf published his De mulierum organis about the female reproductive organs, with prints by Hendrik Bary. De Graaf was the first to conclude that a foetus was the product not just of a man’s seed, but also of a woman’s egg. He discovered what he called blisters, which later became known as Graafian follicles.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.