painting, fresco

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

painted

#

figuration

#

fresco

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

Copyright: Public domain

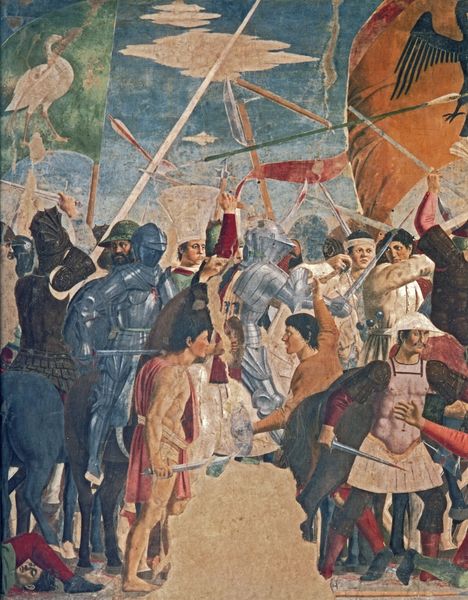

Curator: What strikes me immediately about Antoniazzo Romano's fresco cycle "Stories of the Holy Cross", created around 1492, is the rather muted palette for a scene ostensibly full of triumph. Editor: Yes, I'd agree. There's a somber tone that seems to belie the purported narrative of the Holy Cross. What draws my attention is the materiality. Look at the pigments; they seem earthly, bound, and deliberate—the muted ochres, the washed blues… these are not luxury materials signaling immense power. The artist had to source those materials. Who processed them? For what wages? Curator: Right. Situating it in its context is important: we must remember the fresco comes from a time of deep religious and political transformation. Think of Savonarola's fiery sermons and challenges to Medici rule—Antoniazzo, though part of the Roman school, may have felt these undercurrents influencing even this ostensibly pious work. How does this possibly demonstrate shifts in social power during the Quattrocento? It’s complex because the narrative ostensibly supports the existing power structure of the Church. Editor: Perhaps by examining the fresco itself, we can trace material agency. The fresco technique, while durable, required specific kinds of lime plaster and mineral pigments. These are very particular kinds of skill sets in order to have these works produced on this scale and that denotes material support, and ultimately reflects patronage with the Catholic Church and Papal authority that goes hand-in-hand with social control. It emphasizes not only devotional imagery but also tangible, labor-intensive craft to reinforce a visual narrative that's very tactile. Curator: It's so much more than the literal representation. It represents the intersection of spiritual power, cultural identity, and gender—how are women participating, and how are they represented within these stories, both historically and within the pictorial narrative constructed here? The artist constructs it that women’s agency can also be debated by modern sensibilities in the art production from the period and the artist's individual intent. Editor: And when we consider the physical act, we begin to question who are the figures represented. What choices went into constructing these historical narratives within such specific material constraints that must shape this moment, this intersection of meaning and medium in powerful ways? Curator: Absolutely. Approaching the work through these multiple perspectives gives us an even better understanding of Renaissance culture. Editor: Precisely; from pigment to power, it is the layering of social and material factors in their entirety to truly reveal and inform on cultural works that are lasting today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.