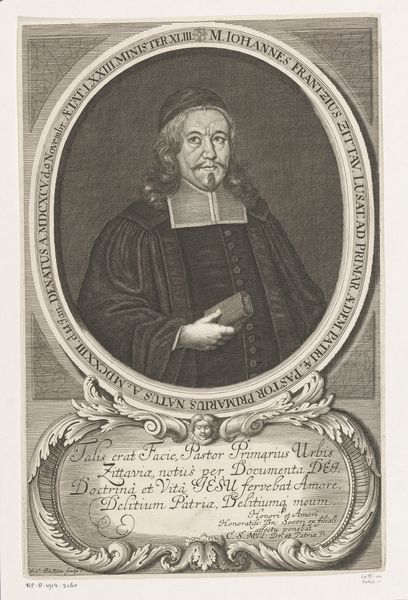

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look closely at this engraving, "Portret van Andreas Glauch." Created sometime between 1681 and 1721, this work offers us a glimpse into the social and intellectual circles of the Baroque era. Editor: The intricacy of the line work really strikes me. The detail in the lace collar, for instance – you can almost feel the texture of the linen. There's an almost obsessive quality to it, a dedication to capturing every minute detail. Curator: Precisely. This print represents more than just Glauch himself. The trappings surrounding him - the elaborate frame, the Latin inscription - speak to his status as a theologian and archdeacon. These were deliberately crafted symbols to convey authority in the public sphere. Editor: And consider the labor involved. Engraving like this was painstaking. Each line meticulously carved, demanding intense skill and time. It makes you think about the workshops and the material conditions surrounding the production of these images. Was it an individual artist or a whole team working to propagate images like this? Curator: Good point. Printmaking, particularly engraving, enabled wider dissemination of images beyond the elite. Although the subject matter here remained connected to power structures, the *means* of producing this allowed wider social accessibility of Glauch’s portrait and by extension, the ideology it embodied. Editor: Looking closer, the expression on Glauch’s face is quite enigmatic. There’s a certain detachment, or maybe it's weariness. Did the artist consciously imbue him with a certain character, or was this a reflection of the conventions of the time? Curator: Conventions certainly played a role. But Baroque portraiture, while adhering to certain formalities, also aimed to capture something of the individual's character. In this case, perhaps an air of scholarly seriousness was considered fitting for his profession. His gaze appears quite commanding. Editor: Thinking about the materials again—the paper, the inks, the metal tools used to carve the plate—it all underscores how the social standing presented to us by this piece would have still required tangible resources and specialized trades. Curator: Ultimately, analyzing prints like "Portret van Andreas Glauch" allows us to deconstruct the visual language of power in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Editor: Exactly, and understanding the tangible aspects of its making adds another dimension, connecting the intellectual and social realms with the labor and material resources of its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.