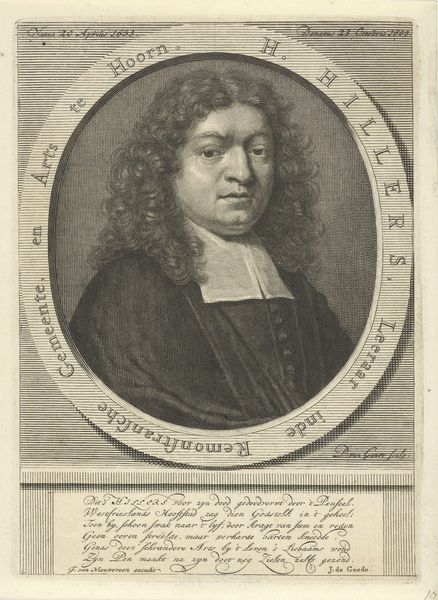

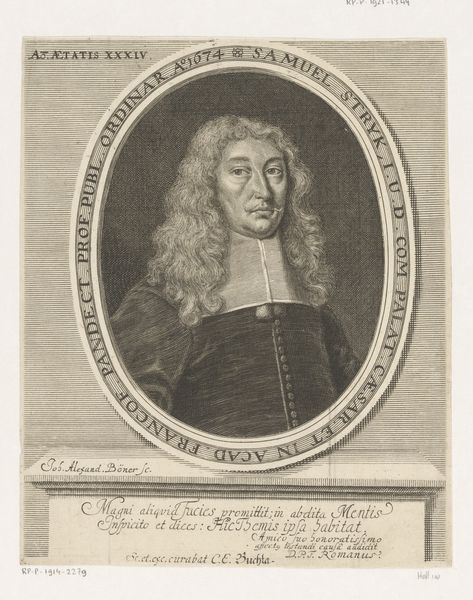

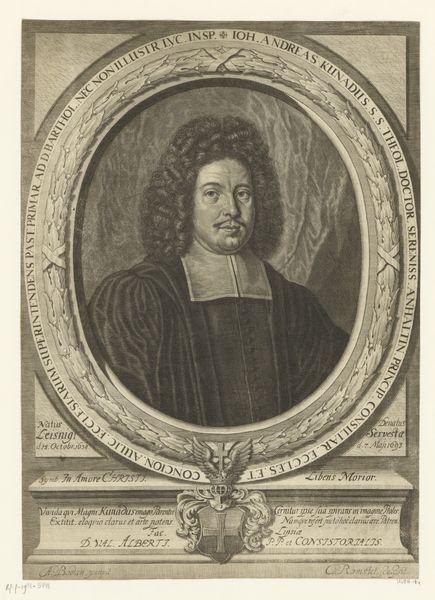

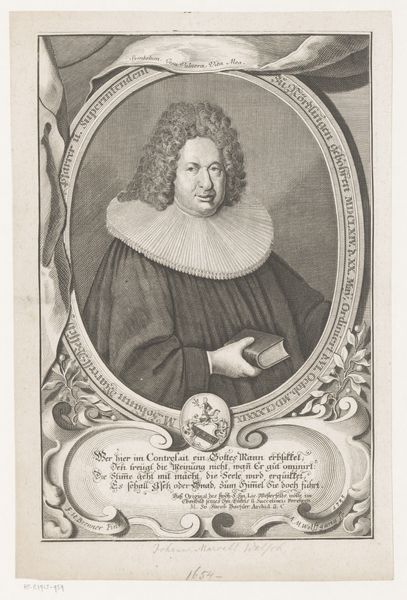

print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

charcoal drawing

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 330 mm, width 218 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

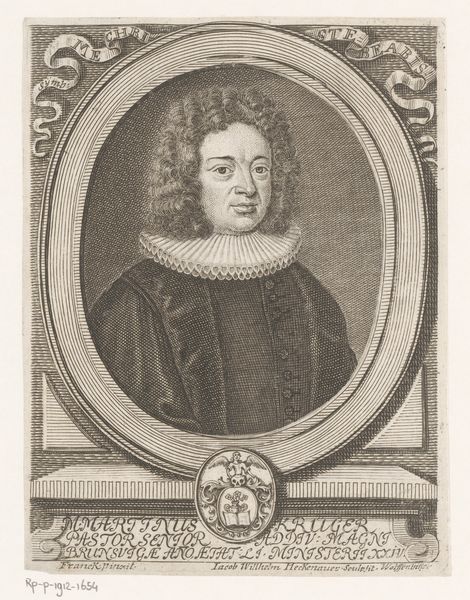

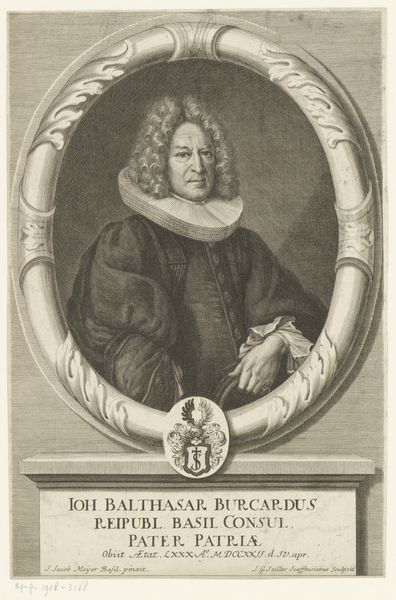

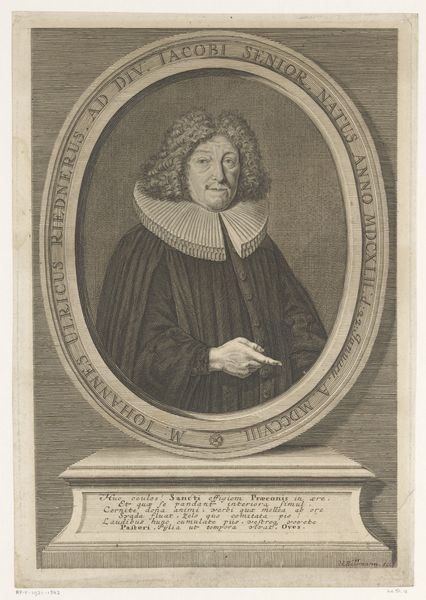

Curator: Before us hangs "Portret van Johann Jacob Vogel," an engraving by Johann Kenckel, dating from 1719 to 1722. Editor: It strikes me as…stately, though somewhat severe. The crisp lines, the formalized pose – everything conveys a sense of controlled authority. Curator: Kenckel created this print, etching into metal, during a period of significant religious and political upheaval, impacting self-representation. Considering the subject's role, might we examine this portrait as a constructed symbol of pastoral authority in the early 18th century? Editor: Precisely. Notice the visual cues: the elaborate ruff, the carefully styled wig—these aren't simply decorative. They speak volumes about status and adherence to specific cultural codes of the time. The oval frame even resembles a commemorative medallion. It certainly positions Vogel as an important figure of his time. Curator: Indeed, and further reinforced by the Latin inscription that surrounds the portrait, celebrating Johann Jacob Vogel as pastor. How do these symbols of religious and intellectual power converge? What historical and religious discourses shaped Vogel’s identity, and how are those reflected in the visual language of the print? Editor: I am immediately drawn to the repetition of circular motifs, like the curls in his hair and that perfectly round collar. These repeated curves lend the engraving a certain softness despite the severe gaze, perhaps softening his image, attempting to make him appear relatable or… even angelic. It gives him an almost halo-like quality. It invites contemplation, urging viewers to find beauty even within those prescribed societal roles. Curator: I think you are right to point out the interplay of severity and invitation here. Kenckel's choices encourage us to interrogate not just Vogel's individual identity, but the construction of authority itself during this turbulent historical moment. Who was he really accountable to, and who did this work aim to impress, reassure, or appease? Editor: Ultimately, viewing this portrait allows a look at the past, letting us connect the intricate symbolic language to an era with very rigid societal rules. Curator: It makes one reflect on how those structures—and perhaps the desire for stability—might be carried over into our own cultural landscapes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.