pencil drawn

photo restoration

old engraving style

historical photography

portrait reference

unrealistic statue

old-timey

framed image

limited contrast and shading

19th century

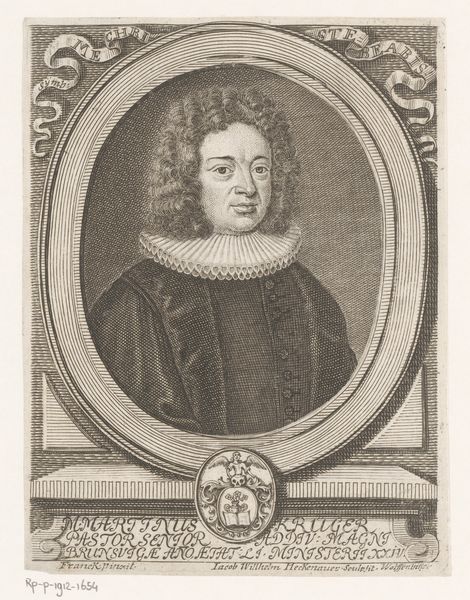

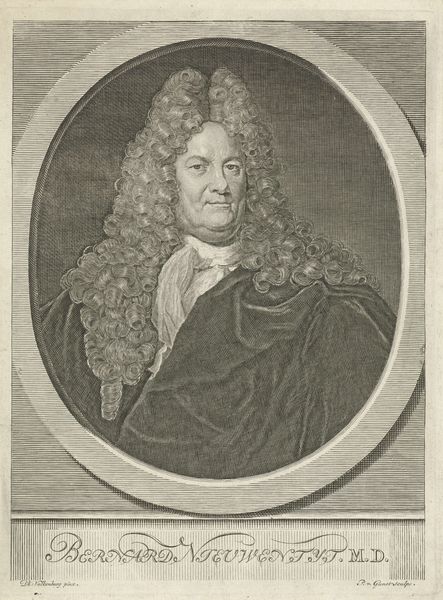

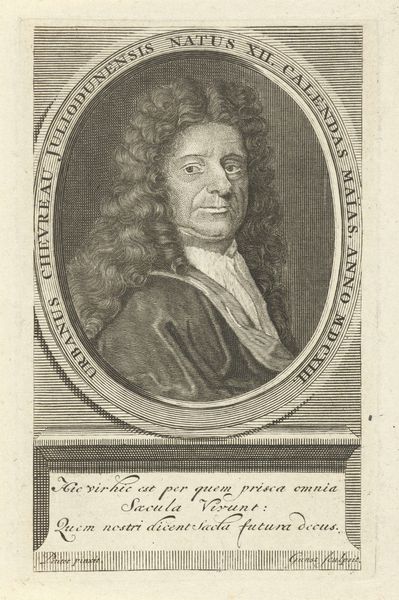

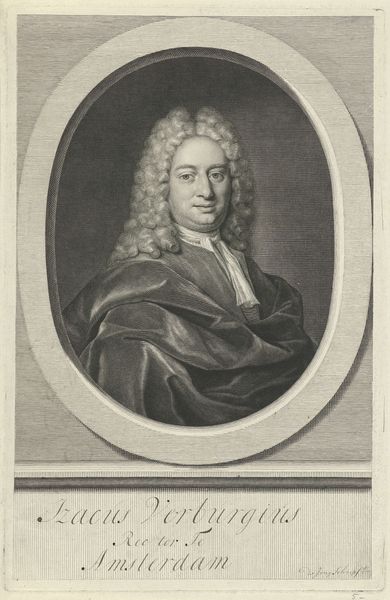

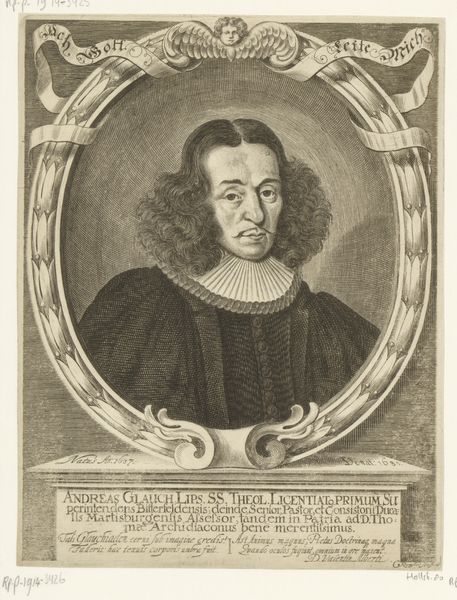

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 88 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It has the air of peering into the past, doesn’t it? It feels like one of those old photographs your grandmother keeps tucked away in an album, the kind you find strangely compelling. Editor: This engraving is a portrait of William Sherlock, created sometime between 1721 and 1771 by Johann David Schleuen the First. The print, residing here at the Rijksmuseum, presents an intriguing example of 18th-century portraiture. Curator: Interesting! An engraving, so like a captured shadow rendered in fine lines. I am taken by that oval frame; ornate but enclosing. Does it feel to you like it’s holding the man captive, preserving his essence in this precise moment? Editor: In a way, that frame represents the societal structures within which Sherlock operated. As the inscription notes, he was no ordinary man—a Doctor of Scripture, Rector of St. Paul's, and royal court preacher in London. The frame, like his societal position, sets him apart. Curator: Royal court preacher…So he carried not just spiritual, but also considerable political weight. Makes you wonder how that affected the message he preached. Was he a firebrand, a comforter, or a shrewd negotiator, weaving threads of faith and diplomacy? Editor: Such positions in the 18th century were, indeed, deeply enmeshed with political power. Engravings like these played a crucial role in disseminating images of influential figures, crafting public perception and solidifying their authority. Think of it as early public relations. Curator: Public relations in ink and shadow, I like that! And seeing it now, I note an angel motif embellishes the top of the frame, as if lending the portrait a touch of heavenly approval. Sly. Editor: It speaks volumes about the relationship between religious institutions, the monarchy, and the visual arts during that era. It all highlights how images like this reinforced hierarchies of power and faith. Curator: Thinking of this image in reproduction... Did people seek copies for their homes to broadcast their association, aspiration, respect? Or was it simply that ‘having your portrait engraved’ signified achievement and permanence? Editor: Both, likely! Portraits like these served as aspirational emblems of status, while simultaneously offering a form of symbolic immortality, a way for individuals to transcend their temporal existence. Curator: A memento mori then, repackaged as status symbol. Our friend Sherlock, preserved for posterity. How fascinating it is that this simple engraving continues to spark contemplation, centuries on. Editor: Precisely! It invites us to consider the interplay of power, image, and representation, reminding us that even seemingly simple portraits are imbued with complex cultural significance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.