Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

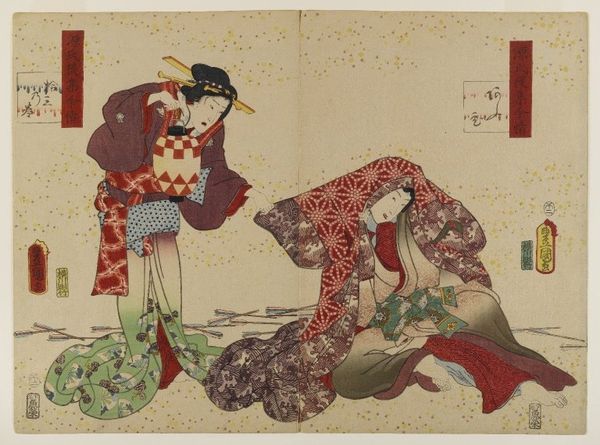

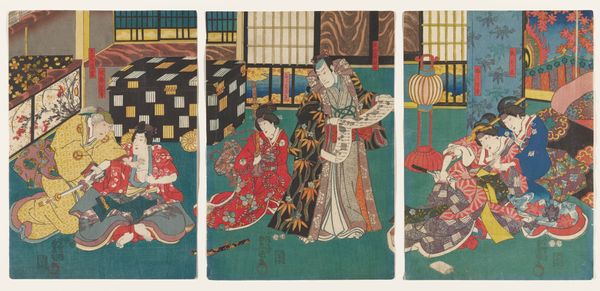

Curator: Here we have Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's woodblock print, "The Story of Okoma of Shirokiya," created in 1886. What’s your initial read of this diptych? Editor: It strikes me as an odd juxtaposition. On one side, a poised woman in elaborate textiles, and on the other, a man undergoing what appears to be a rather painful shaving! The contrast is stark, unsettling almost. Curator: Indeed. The woman is Okoma, a tragic figure whose story resonated deeply in Japanese culture. Notice how Yoshitoshi has structured the composition. Her side, with its cool blues and precise patterns, versus the right side which depicts...well, let's delve into the shaving scene. The suffering man would be Denshichi. Editor: Ah, I see now. Beyond the apparent discomfort, I sense a commentary on societal beauty standards. Okoma, the epitome of grace, is paired with Denshichi enduring physical pain for... presumably, the sake of appearances? What sort of emotional landscape can be extrapolated from the symbols depicted within? Curator: A pertinent observation! We should acknowledge that Yoshitoshi was very conscious about texture and patterns in portraying the figures and setting them apart in space. Let's think about it further: each element is positioned with purpose, orchestrating your gaze. Editor: Yoshitoshi also worked this as narrative, presenting Okoma on one side and her husband on the other; I can detect his agony conveyed via cultural memories. Are those specific textiles used by the artist meant to imbue his status or profession? It definitely appears like a narrative exploration. Curator: Without a doubt. We can see Yoshitoshi exploring historical narrative conventions through visual arrangement as a stylistic device, with careful chromatic considerations creating a certain affect. He uses colors almost as a tool of delineation, to enhance readability, Editor: The diptych, then, becomes a multifaceted symbol—a representation of the delicate balance between the ideal and the real, beauty and suffering, stoicism and struggle as seen in ukiyo-e? What did it represent to contemporary viewers? Curator: Exactly. It offered them a visually compelling moral, expressed using a symbolic tale embedded in woodblock art history, echoing and altering previous conventions for emphasis. We understand it to create new formal arrangement to give significance, just as Yoshitoshi likely hoped. Editor: And that's perhaps the enduring appeal, its ability to generate layered interpretations by formal composition combined with visual storytelling through culturally-dependent motifs.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.