drawing, graphic-art, print, etching, woodcut, wood-engraving, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

# print

#

etching

#

woodcut

#

united-states

#

portrait drawing

#

wood-engraving

#

engraving

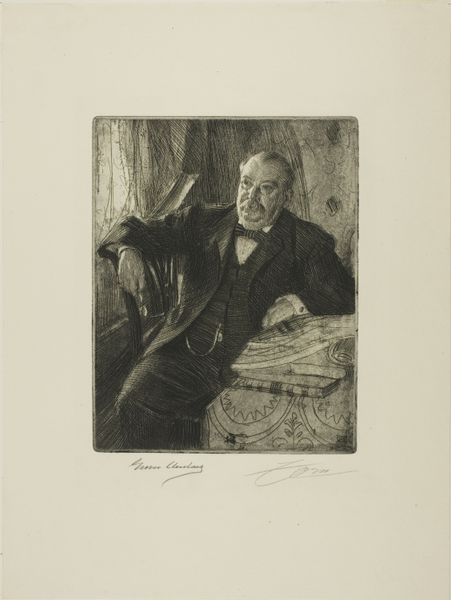

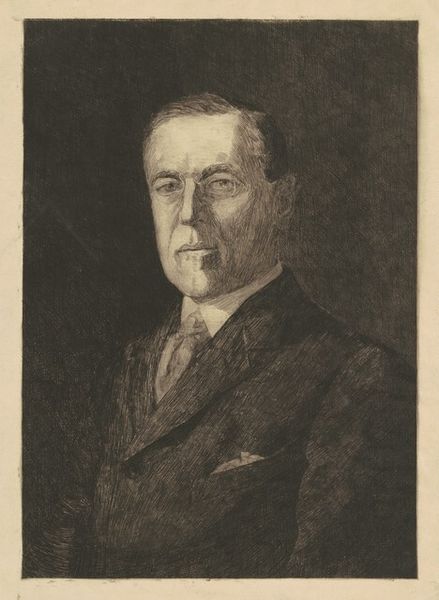

Dimensions: 9 13/16 x 6 15/16 in. (24.92 x 17.62 cm) (plate)15 5/8 x 12 in. (39.69 x 30.48 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

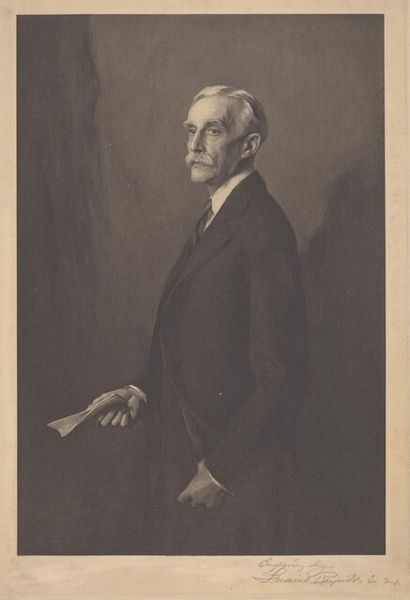

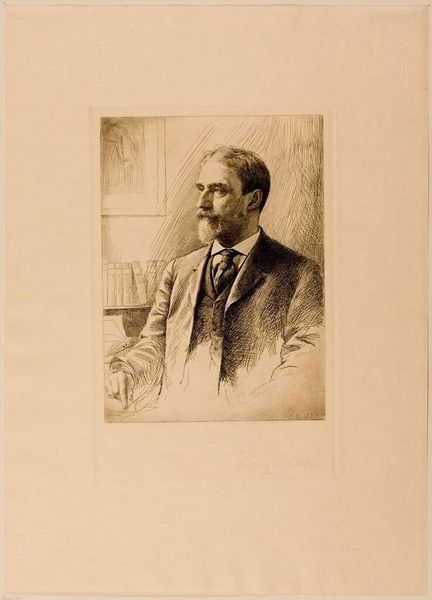

Curator: Here we have Timothy Cole’s "Wilson," a striking portrait created in 1918. It seems to be a print, perhaps an engraving or woodcut? Editor: The somber mood really hits you first, doesn't it? And the scale - I imagined this as a small, intimate piece, but seeing it now, it's grander than I expected, it looms like a gravestone. It certainly suggests something more than simple portraiture. Curator: Indeed. Cole, who primarily worked as a wood-engraver, often reproduced existing portraits in his distinct style. Looking at Wilson here, his approach adds a certain depth beyond mere likeness. One could read Wilson’s presidency through the sharp angles and deep shadows. Editor: Absolutely, and one immediately starts thinking about the context: 1918, the tail end of WWI, a pivotal time. Here sits Wilson, the intellectual idealist, his expression a kind of exhausted contemplation. The world had shifted so violently, it's almost like he's pondering how his utopian vision squared with the realities of war. Curator: There's a fragility hinted at in his gaze that Cole really captures. Remember Wilson suffered a stroke the following year. Seeing him rendered with this level of detailed introspection, it speaks of a vulnerability often glossed over in depictions of powerful men. Editor: Right, and consider that the style echoes the progressive era and it’s fascination with efficiency. This is visible even in the meticulous strokes of the engraver. It asks how can we create a more “perfect” or “moral” society. What is more jarring, of course, is the way eugenics rhetoric often found itself in these spaces. What kind of vision does this morality really serve? Curator: That tension makes the work deeply unsettling, especially given how Wilson's legacy has been reassessed in terms of race. Editor: Ultimately, the art stands as this stark representation of the complicated threads of the early 20th Century. It forces you to confront how images function in crafting a president's narrative. It's art functioning as propaganda...but then disrupted. Curator: What begins as a stately portrait ultimately prompts so many urgent, painful, fascinating questions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.