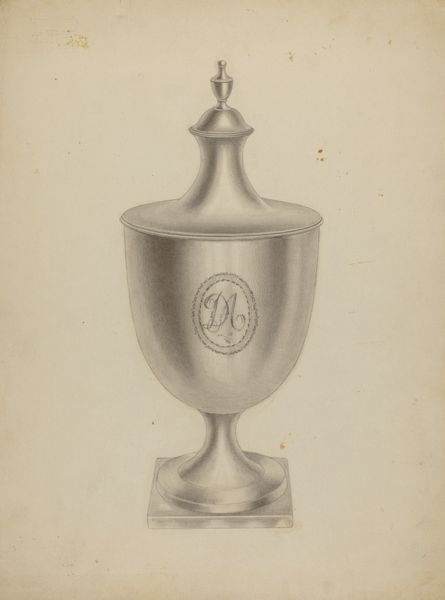

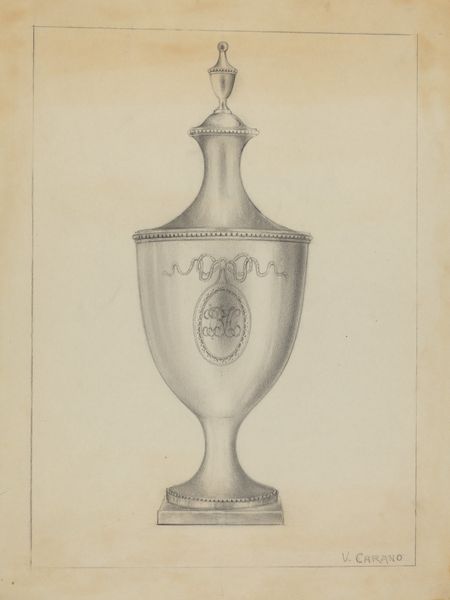

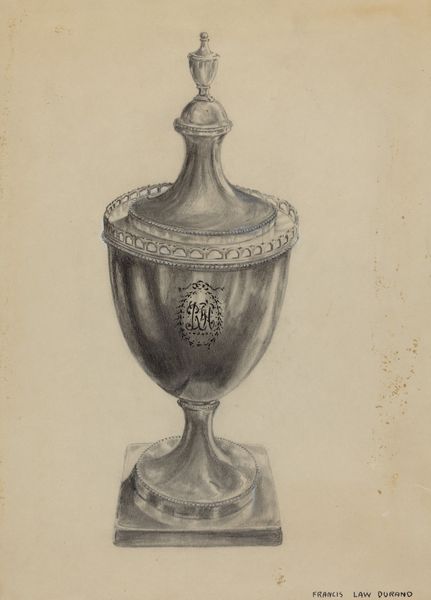

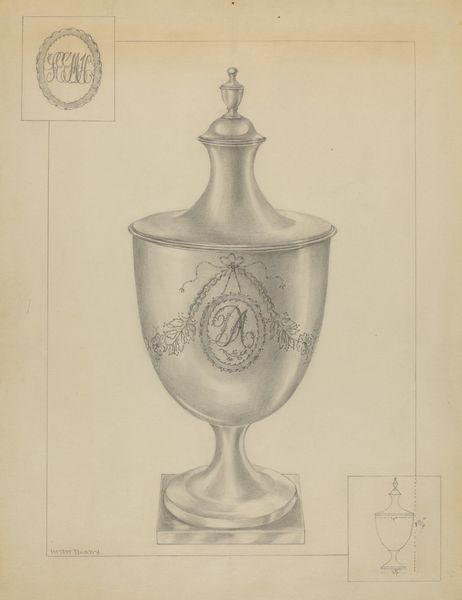

drawing, print, pen

#

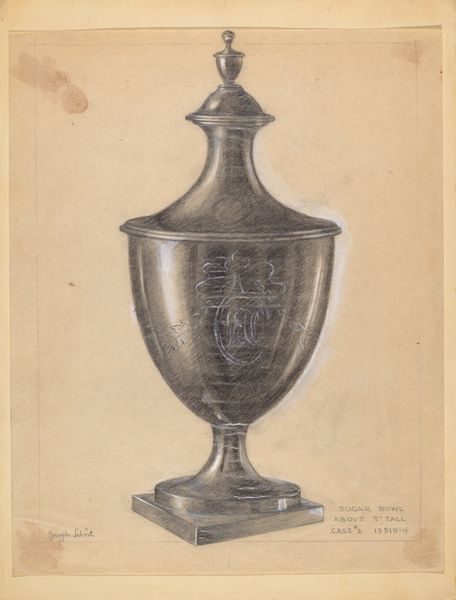

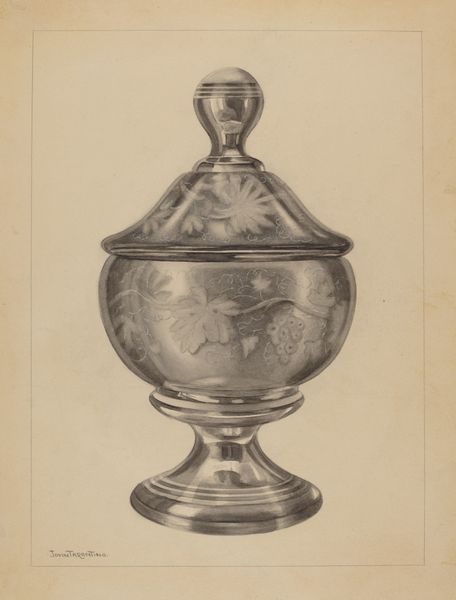

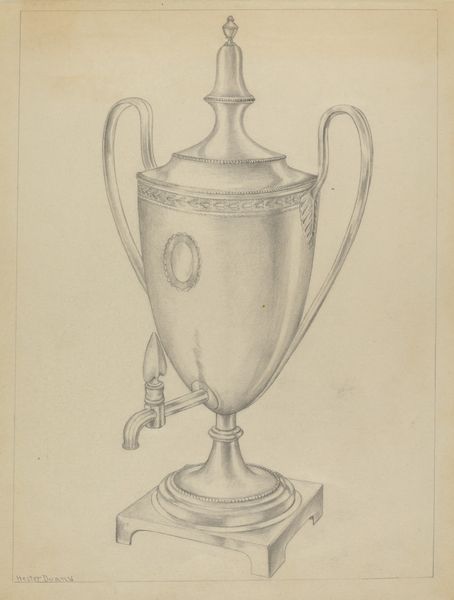

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

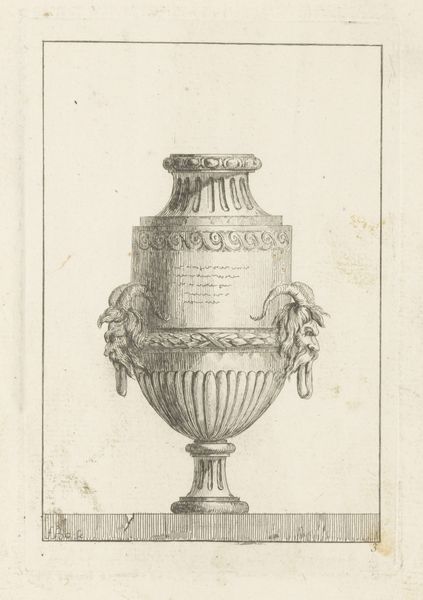

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

fading type

#

geometric

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

pencil work

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: height 174 mm, width 135 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jacques Juillet’s “Vase with Masks and Cornucopia,” created in 1768. It’s a delicate drawing, seemingly printed, showing a covered vase. What strikes me is how precisely the vase’s ornamentation has been recorded in such a light pencil work. What can you tell me about it? Curator: The precise detailing indeed speaks to the economic imperative driving printmaking at the time. Note the aged paper, and imagine how this piece may have functioned. Editor: Almost like a craftsman’s manual? A way to distribute designs? Curator: Exactly! This wasn't necessarily ‘art’ as high culture, but a mode of design communication tied to the decorative arts, neoclassical style, and probably intended for reproduction by artisans and their workshops. Think about the material value— or lack thereof. How does that influence our understanding? Editor: So, the material of this drawing and its print suggest it was meant to be widely available. It’s a means to share and sell a design to craftsmen, focusing less on the uniqueness and more on the reproduction and utility of the product. Curator: Precisely. It forces us to consider art as not just an aesthetic object, but as a piece of material culture tied to a network of production, distribution, and ultimately, consumption. And think about the implications of neoclassicism! The replication and use of classical motifs democratizes aesthetics... for a price. Editor: I see what you mean, it's fascinating to consider the artwork less for its aesthetic presence and more for the labor and materials connected to its function in 18th-century design. Thanks for expanding my understanding of prints and material purpose. Curator: It challenges what constitutes art and for whom; an endless journey for us all.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.