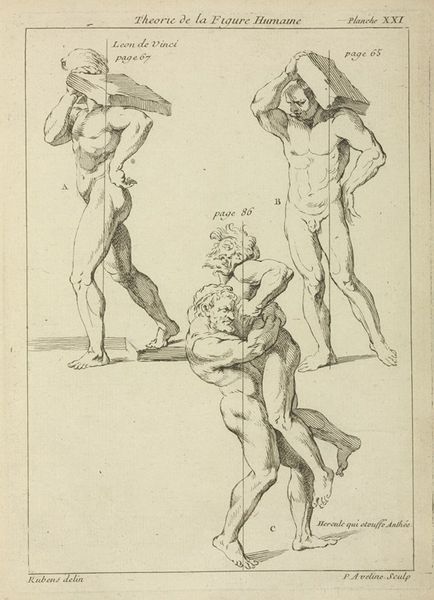

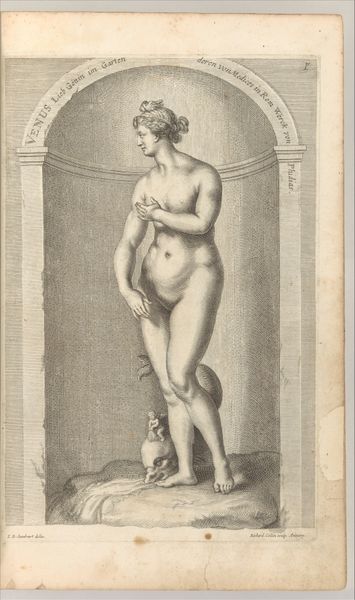

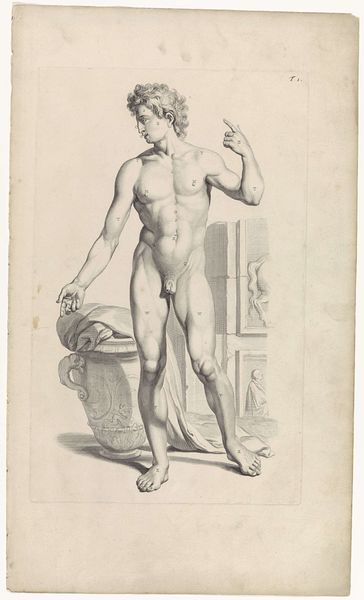

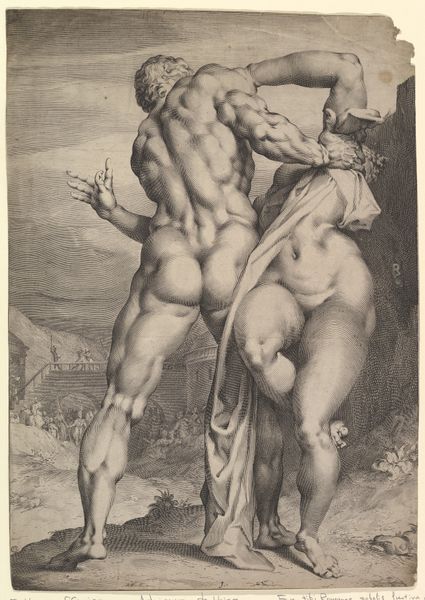

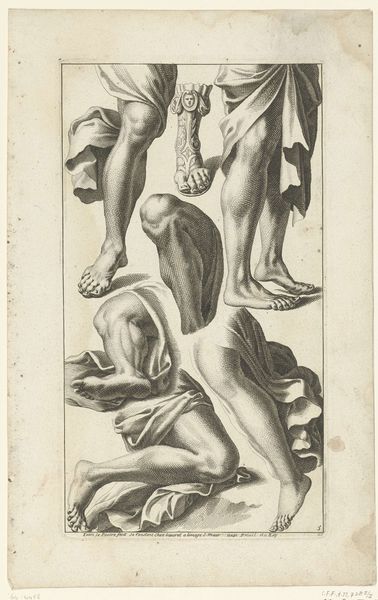

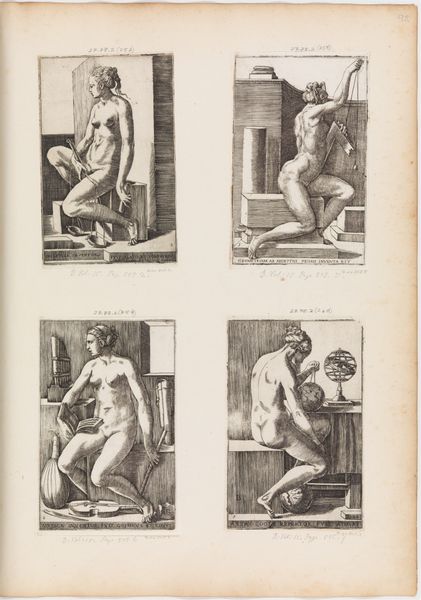

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 272 mm, width 153 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jean Le Pautre's "Studie van putto, oudere vrouw en zittende man," an engraving and print dating back to somewhere between 1682 and 1706, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s striking how dynamic the composition feels, even with its limited palette. The contrast between the robust figures and the delicacy of the engraved lines really grabs you. It gives a real sense of the Baroque period, its sensuality. Curator: Absolutely. What’s interesting here is the tension between what seems to be a study - focused on the textures and the effects produced by light - and how the subjects may relate to a bigger, perhaps historical painting. Lepautre clearly focused on how the human form is rendered through the burin’s capacity for fine detail and the effects it produces on the paper. Consider the labour needed to achieve that skin texture, its relationship to broader cultural constructions and understanding of the body. Editor: Exactly! Think about who these figures might represent, who had the privilege of being memorialized like this and whose stories are erased from art history. There’s the youthful, winged putto, representing innocence and divine love perhaps, juxtaposed against the aged faces, maybe hinting at mortality. How does it mirror the power dynamics of that period? Curator: It leads us to examine the whole studio system prevalent at the time, of mass-producing drawings for distribution through an established marketplace. The work isn't "original" in our romanticised understanding of individual expression; instead, it belongs to a collective of skilled labourers whose products circulate commercially, reaching far beyond the artist's immediate reach. Editor: And those lines, etched so deliberately – they carry the weight of not just the artist's hand, but the society’s ideals regarding beauty, piety, and the roles assigned within. I can't ignore the idealized male forms as expressions of dominant power structures of the era. Curator: Acknowledging this distributed practice helps demystify art production itself, enabling us to see art not only for symbolic capital, but also a product borne out of concrete modes of production, shaped by materials, tools and collaborative labor. Editor: Indeed. The etching, while beautiful, echoes of broader social structures—raising interesting questions about visibility and historical accountability within artistic creation. Curator: Thank you, this conversation illuminates not just what the artwork shows, but what it obscures as well. Editor: And, as always, leaves us contemplating what responsibility artwork of this kind have for reflecting society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.