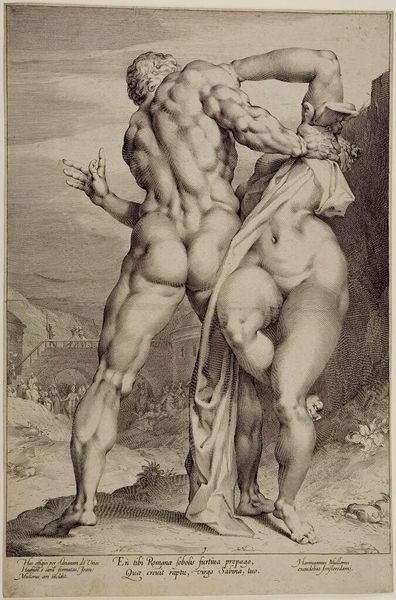

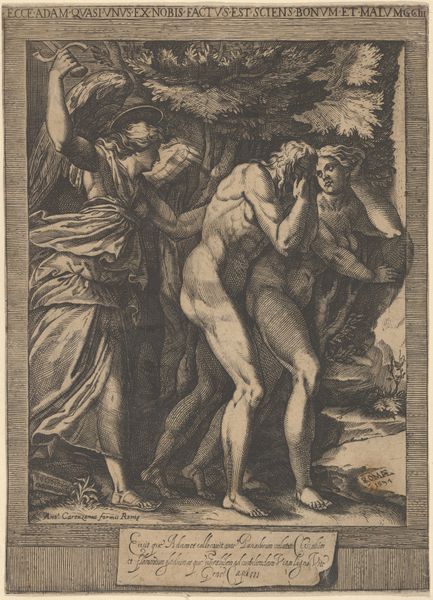

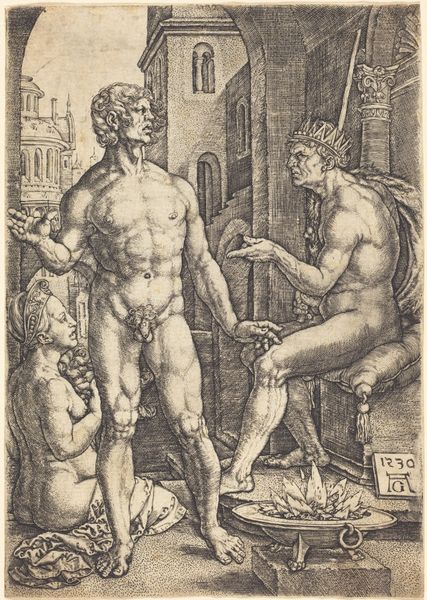

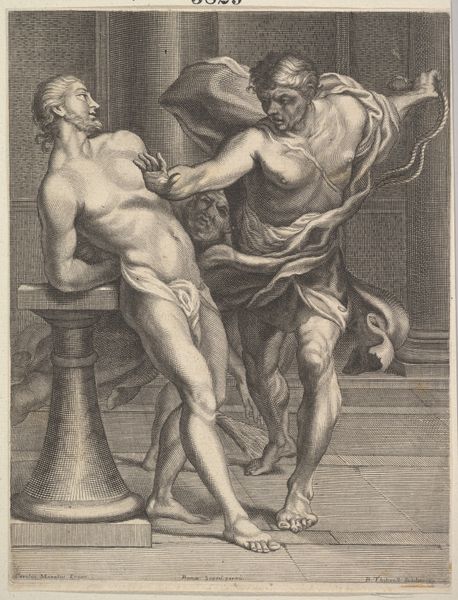

The Abduction of a Sabine Women (view from behind) 1593 - 1603

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

female-nude

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

#

male-nude

Dimensions: Sheet (trimmed): 15 9/16 in. × 11 in. (39.6 × 28 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This engraving, crafted by Jan Muller between 1593 and 1603, is titled "The Abduction of a Sabine Women (view from behind)". What are your immediate thoughts? Editor: Brutal. Muscular figures rendered with extreme attention to anatomy... almost overwhelmingly so. The tension in their poses really tells the story. It's also printed on paper, and look at the density of lines, what an intense labor that was! Curator: Absolutely. And think of the socio-political context in which Muller was working. History painting served as a potent tool for constructing collective memory. This work taps into the foundational narratives of Rome, where the Sabine women, through violent abduction, contributed to the Roman lineage. Editor: And it's not just about the history, but the physical act of making the image, all those tiny lines meticulously etched. Each line contributes to the depiction of flesh, force, and… frankly, the brutality of the event. Did the consumption of prints like this normalize or even glamorize violence? Curator: It’s certainly a question worth asking. Printmaking democratized images. Replicating such classical scenes enabled the circulation of not just visual narratives but also political and social ideologies. And while Muller produced the print, the scene is adapted from Giambologna's sculpture; circulation of artistic ideals also mattered. Editor: Right, the printmaking process further transforms that idealized form for broader consumption, thus reinforcing this… aesthetic. It really forces us to consider what kinds of values were circulating within these networks of production. Curator: Furthermore, it places institutions like The Met at the forefront of debates regarding cultural patrimony. What narrative are we continuing to perpetuate by displaying this today? Editor: That's key, because the life of this image certainly doesn't end in the 16th Century. Thanks for helping me look closer—I appreciate the emphasis on process, labor, and the way images mediate historical ideas and political tensions. Curator: The pleasure was all mine! Contextualizing the social and political functions of these art objects deepens the ways we come to terms with them as cultural commodities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.