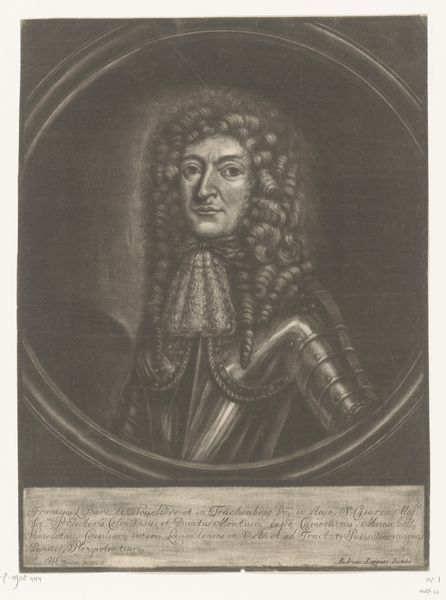

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait reference

#

limited contrast and shading

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 303 mm, width 211 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s consider this engraving of Michaël Korybut Wiśniowiecki, King of Poland, created sometime between 1669 and 1700 by Jan van Somer. It offers such a fascinating window into the technologies of power at play in image making. Editor: Wow, okay. First impression? A bit… intense. All that cascading hair! He looks almost overwhelmed by it. Though maybe 'intense' isn't the right word. 'Pensive', perhaps? There's a weight to his gaze. Curator: I’d say it's deliberately weighty. Notice how the engraver uses line and shadow to create a sense of gravitas. The armor, the elaborate collar, all these are constructed using precise techniques, reflecting the demands of the king’s royal status but also the artisan's labour. Engraving allowed for dissemination, reproduction and accessibility to portray the King's rule across geographical contexts. Editor: Right. He’s got that kingly “look," that "I contain multitudes of lands" vibe. I’m interested in the material qualities. Is that paper? And the feel of the engraved lines under your fingertips must be gorgeous. Does the work surface provide additional interpretive context of dissemination for Van Somer's portraits? Curator: Precisely! Consider also the implications of Baroque aesthetics here. It's all about grandeur and authority. Yet, this engraving is inherently a reproductive medium. The image's power rests on its potential for distribution and replication to promote propaganda efforts, making its effect cumulative as the image spread. Editor: Absolutely, a proto-meme for royal propaganda, if you will. It’s clever how the limited contrast almost flattens him, turning him into a symbol rather than just a dude with fantastic hair and hefty armor. What was the relationship of engraver and King when Van Somer completed the portrait? Was there mutual gain, recognition, a formal commission for him? Curator: These questions cut right to the heart of art’s social function! Likely this portrait was commissioned and the social capital exchanged would cement power relations of patronage and influence. Editor: Okay, that gives the engraving new meaning. This isn’t just a picture; it’s a record of obligations. It captures the political theater as much as a likeness. I think the work offers a sharp meditation on how power manifests in both an individual and larger context. Curator: I agree. By exploring the materiality and modes of production we gain so much deeper understanding of what an image means.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.