#

pencil drawn

#

light pencil work

#

photo restoration

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

old-timey

#

19th century

#

portrait drawing

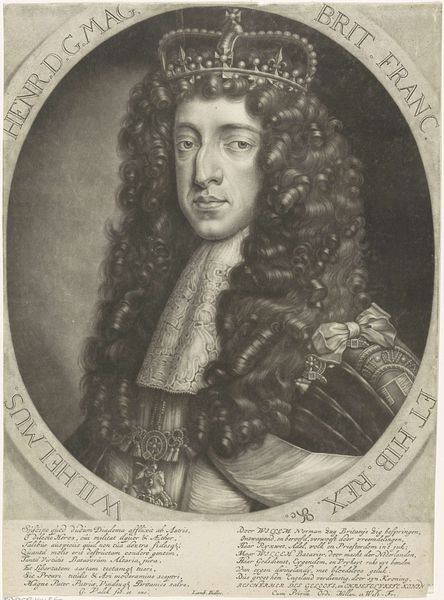

Dimensions: height 348 mm, width 255 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here in gallery 12, we have a portrait of Willem III, Prince of Orange, an engraving created sometime between 1688 and 1726. It is currently attributed to Gerard Valck. Editor: My initial thought is how labor-intensive the process must have been to achieve such delicate lines. Look at all those intricate curls! I am immediately struck by the technical skill required, it feels quite ornate to our eye. Curator: The level of detail certainly speaks to the techniques involved in portrait engravings during this period. Prints like these played a crucial role in image dissemination and constructing public personas of leaders like Willem III. Editor: Exactly. Think of the material aspect; the copper plate itself, the inks, the paper. And the time investment to create such a likeness! How many prints could they realistically make in a day? Curator: And let’s not forget about how the cost and availability of these prints were crucial. These were aimed towards specific sectors of society and reflect a definite projection of power. Distributing engravings allowed a ruler's image, and therefore, their authority, to be propagated far and wide, shaping public opinion. Editor: It's fascinating to consider this as a manufactured object meant to broadcast a message. He looks suitably regal in his armor. The level of work puts our modern modes of reproduction to shame; each piece had the labor of an artist in its making. Curator: And not just an artist, but an entire network of engravers, printers, and distributors. Studying this print offers us a window into the mechanics of early modern media and its effect on the politics of the time. It's a testament to the power of images. Editor: Definitely a unique material record—from metal to paper—each stage has shaped meaning. That attention to process adds to my appreciation for this portrait. Curator: Indeed, it goes beyond being merely a portrait; it’s a crafted message meant for public consumption in a very specific historical context. Editor: So, what begins as an intimate portrait becomes a political tool through production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.