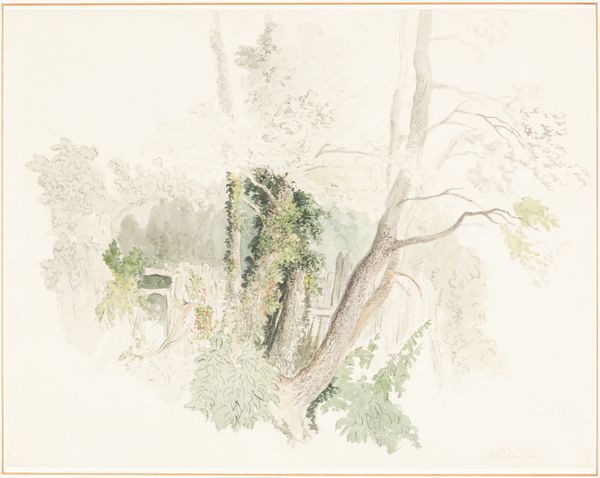

painting, watercolor

#

water colours

#

painting

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: height 258 mm, width 341 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

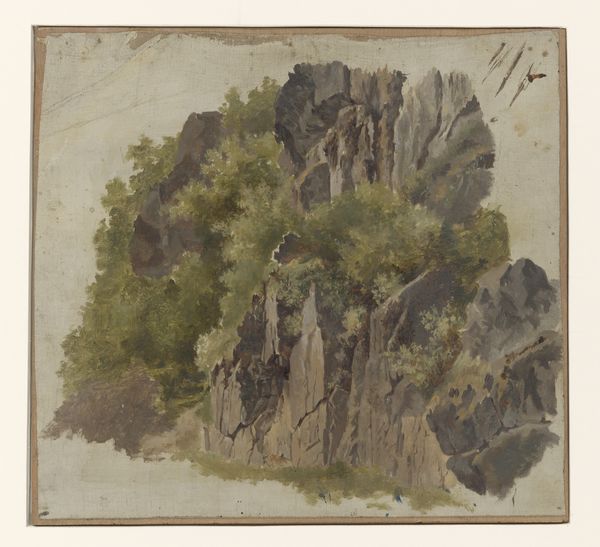

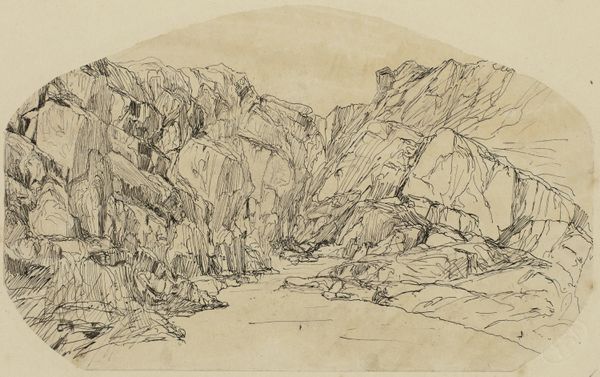

Curator: Before us is Johannes Tavenraat's "Rocks and Vegetation," a watercolor created around 1840, currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It feels immediately… geological. I'm drawn to the textures, the way the watercolours mimic the rough surface of the rocks, and the cool palette evokes a sense of timelessness. It's almost monochromatic. Curator: It is a striking use of watercolour for representing landscape. Consider the social context: Tavenraat was working during a period where landscape painting was used to assert national identity, a form of visual inventory and celebration. But there is nothing grandiose here. Editor: No, it feels intimate, personal. It almost gives the rocks and vegetation a human presence. Look at how the cracks and crevices create what look like faces. I am wondering about its symbolic weight, what could the rock formations themselves suggest about resilience, the ability to endure. Curator: That's interesting because the choice of such a seemingly mundane subject avoids the typical Romantic heroic landscape. One could see this quiet realism as an emerging artistic trend, away from bombast and towards quiet contemplation of nature’s details. Perhaps the rise of scientific observation influenced artistic choices as well. Editor: Definitely, the vegetation is almost overflowing with a life of its own; notice the placement. Could this be about nature slowly reclaiming territory, almost an active process of regeneration, using those symbols within symbols, that idea that things do continue, nature does reclaim. Curator: What I find compelling is the interplay between objective observation and subjective feeling. While ostensibly a realistic study, the tight cropping of the image and limited color palette evoke an almost dreamlike quality, perhaps mirroring the changing social attitudes and values around industrialization during the 19th Century. Editor: I agree! The lack of human figures throws into focus the quiet power of raw nature. Reflecting on it, its visual narrative revolves around this endurance that can resonate at a deeply personal level for everyone. Curator: It is, in a quiet way, very striking. A subtle reminder that we are simply transient observers within a longer ecological and geological timeframe. Editor: Absolutely. I appreciate now how this quiet realism, amplified through careful symbols, manages to speak so loudly to us today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.