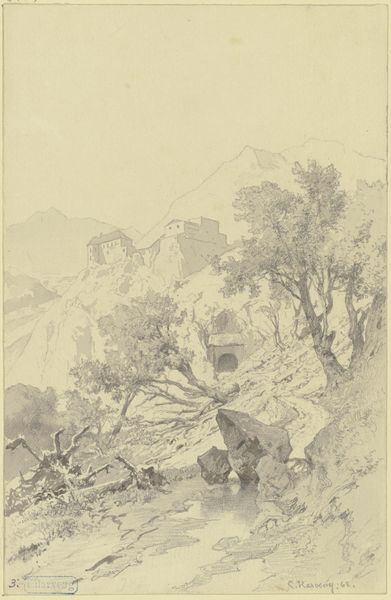

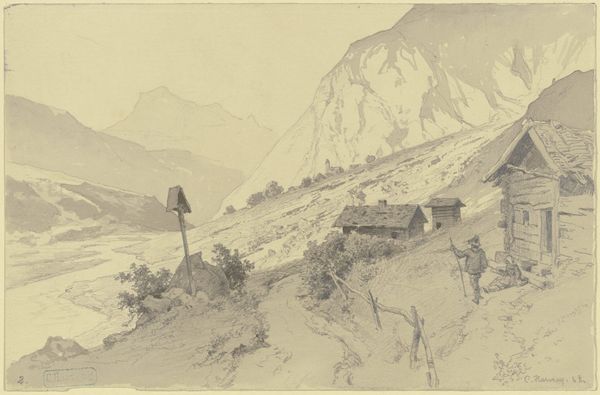

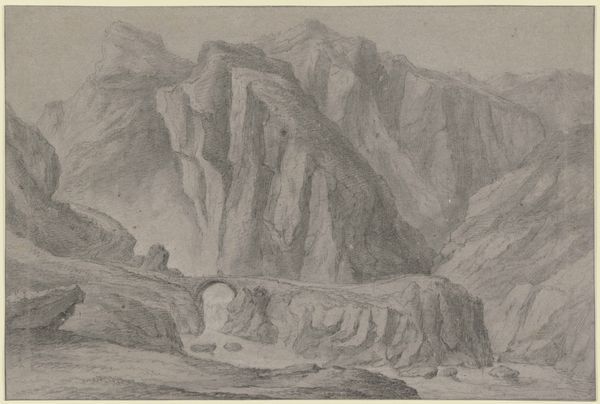

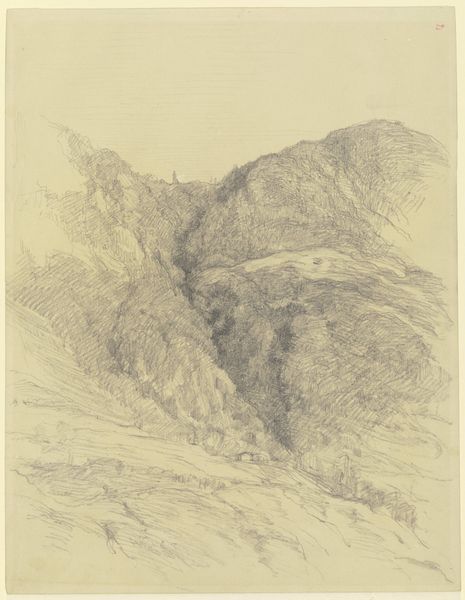

Befestigte Straße entlang einer Felsklamm bei Reichenhall 7 - 1858

0:00

0:00

Copyright: Public Domain

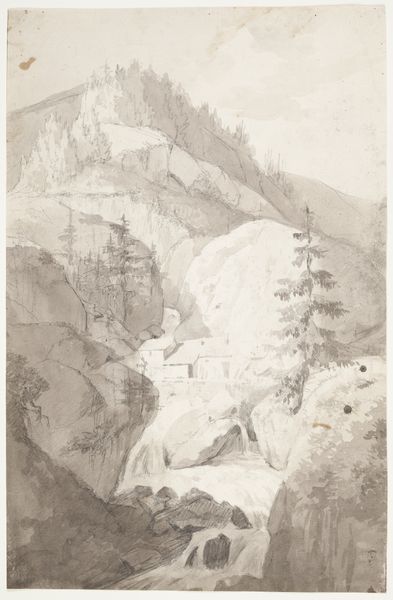

Curator: Wilhelm Amandus Beer's drawing, "Befestigte Strasse entlang einer Felsklamm bei Reichenhall," created around 1857-1858, captures a view now held in the Städel Museum's collection. What’s your first reaction to this scene of a road carved into the mountains? Editor: I’m immediately drawn to the almost precarious placement of that road and the little figures moving along it. The sheer scale of the landscape is so overpowering; it evokes a very particular feeling of sublime insignificance. Curator: Beer rendered this in pencil and chalk. Note the varying pressure; look closely at how the chalk emphasizes the rough textures of the rock face juxtaposed against the more delicate strokes defining the distant mountain range. The production values mirror a Romantic obsession with nature's immensity. Editor: The road, though! Isn't it a powerful symbol here? The twist and turn follows the landscape and invites the viewer into the depths. But also, there is something so potent about humans trying to shape nature into submission. I can’t help but think of how ancient roads connected trade, ideas, empires—it is never simply about the terrain. Curator: True, but from my viewpoint, this civil engineering represents a massive reconfiguration of labor and materials. Consider the labor that carved through solid rock with the technologies available then. The social cost must have been immense. And what was it really "for"? This wasn't necessarily a Roman road. It was a deliberate attempt to profit from the region, or move resources elsewhere. Editor: Of course, that makes sense. The winding road becomes a metaphor of commercial exploitation of nature, very good. But doesn't the contrast of its vulnerability in this wild setting enhance the scene’s overall impact? Like so many roads that wind toward religious destinations such as temples. Doesn't that make you consider if there is any religious symbolism hidden here? The high Romantic style favored grand archetypes. Curator: I see your point, yes. The composition almost reveres this act of transformation—altering nature’s form. But I circle back to consider it in light of production and consumption—materials brought and goods taken. And ultimately, by framing it as a drawing that can be purchased. Editor: Both material change and conceptual symbols. It's a delicate balance that resonates even today. Thank you. Curator: And to you. Viewing it through a slightly different lens always offers new appreciation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.