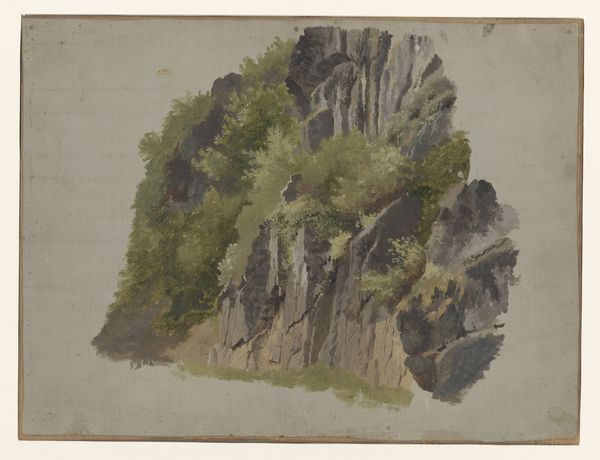

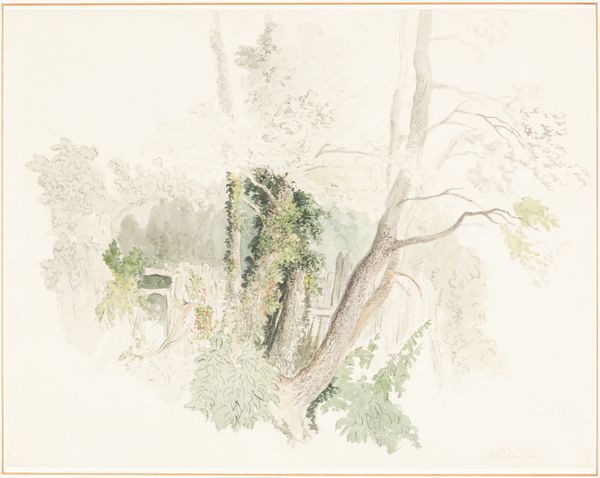

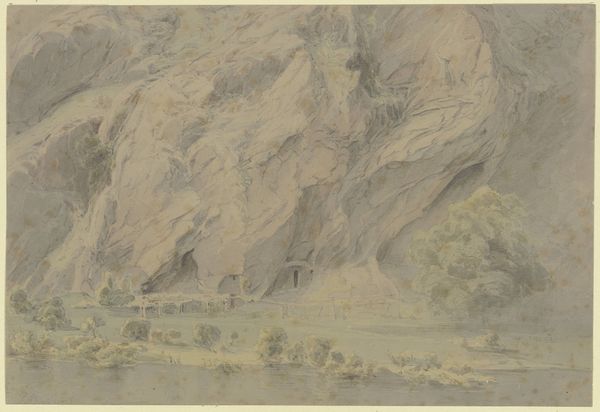

painting, watercolor

#

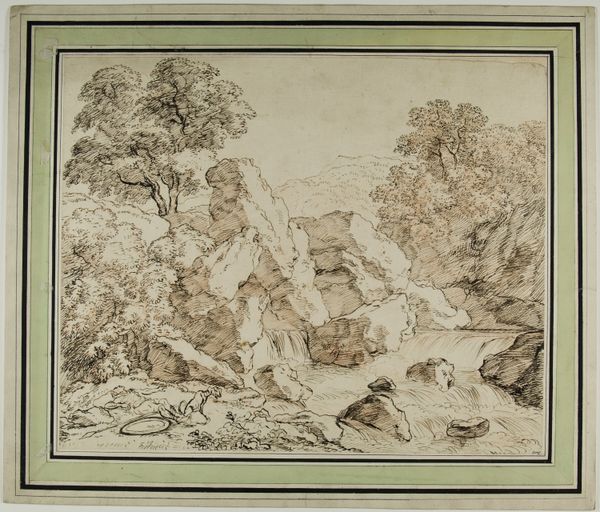

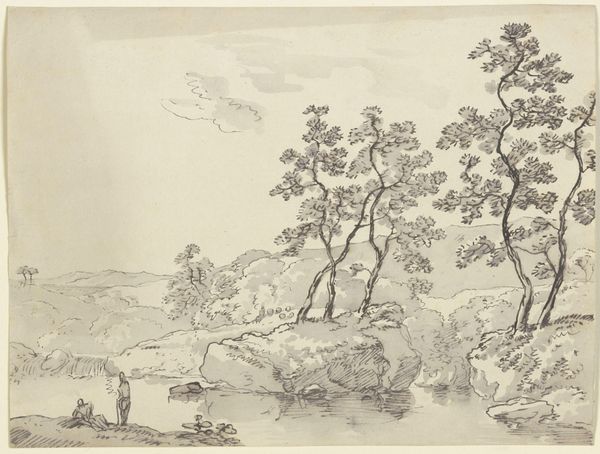

water colours

#

painting

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 246 mm, width 267 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Johannes Tavenraat’s “Rocks and Vegetation,” created around 1840 using watercolor. There’s a kind of rugged, almost imposing feel to this rock formation. What do you see in it? Curator: Well, the immediate thing that strikes me is the artistic shift toward the celebration of nature that was taking place at that time. You see this a lot during the Romanticism era. What I find interesting here is the implied public consumption, the rising interest from wealthy bourgeois in picturesque nature. Editor: You mean, people started wanting landscape paintings more? Curator: Exactly. With industrialization transforming landscapes, these watercolors helped construct a visual ideology around nature – untouched, sublime, a retreat from urban life. Tavenraat and his contemporaries contributed to that ideal. It became a commodity. Do you see any traces of that commercial aspect here? Editor: Maybe in the way he’s made the rocks almost beautiful? Less about accuracy, more about feeling? Curator: Precisely! Think about where this painting might have been displayed – in a bourgeois home, signaling taste and a connection to an idealized nature, maybe sparking conversations, bolstering status. That display is just as important as the art itself. Editor: So, the image itself plays a role in wider cultural stories about nature and social class? That's really interesting to think about! Curator: It is, and understanding that link helps us see this landscape in a completely new way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.