#

pencil drawn

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

possibly oil pastel

#

charcoal art

#

pencil drawing

#

charcoal

#

pencil art

#

watercolor

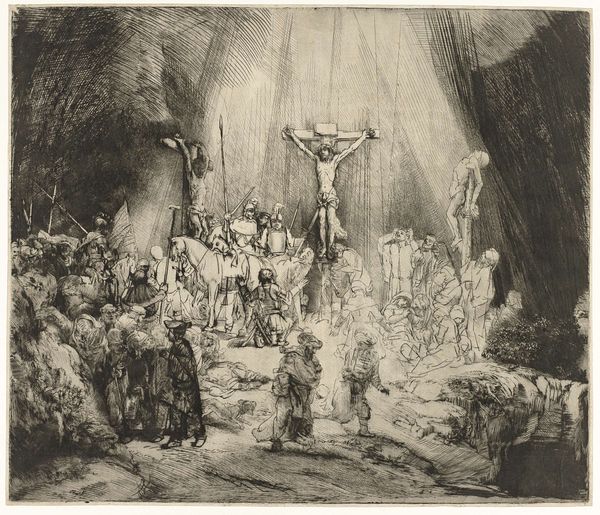

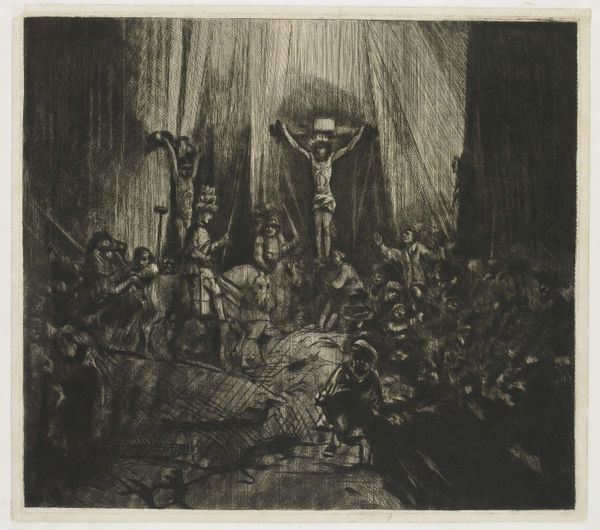

Dimensions: height 387 mm, width 455 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

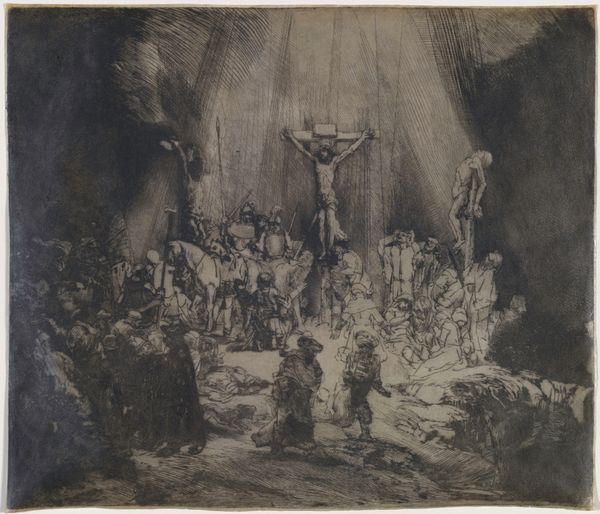

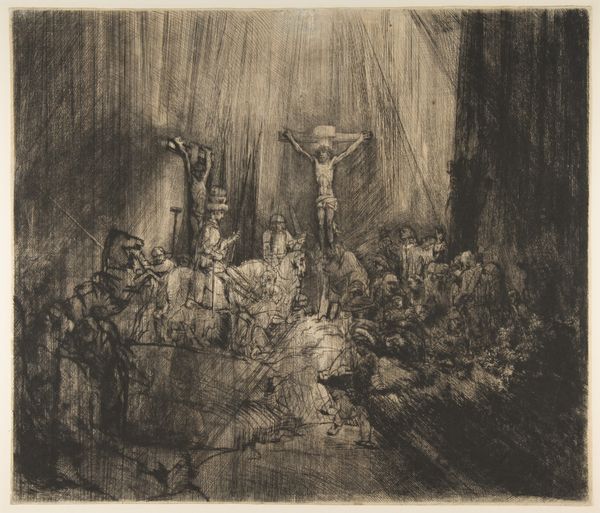

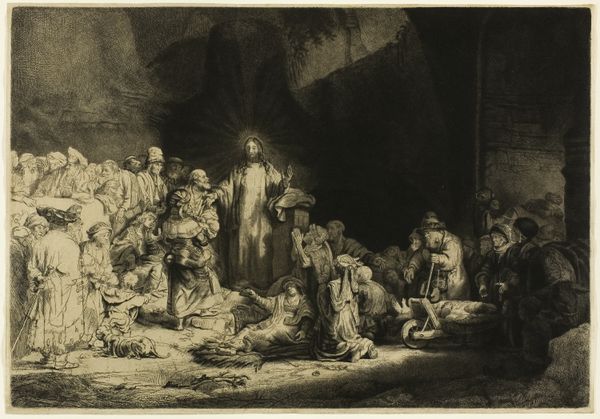

Rembrandt van Rijn rendered “The Three Crosses” using drypoint, a printmaking technique, to capture a somber crucifixion scene. The three crosses themselves dominate the composition, serving as stark symbols of sacrifice, each figure impaled is an icon of despair. Throughout history, we see the cross emerge in various forms—the ankh in ancient Egypt, the solar cross predating Christianity—always representing a meeting point, a convergence. Here, the convergence is one of immense suffering. Note the interplay of light and shadow; Rembrandt employs darkness to amplify the emotional weight of the scene. This echoes the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, who also understood how light could carve out emotion. Consider how this image resonates with our collective memory of loss and redemption. The cross, an instrument of torture, transformed into a symbol of hope. It is a cyclical progression, resurfacing through time, its emotional power enduring.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

When you scratch a line in an etching plate, it produces a small raised edge called a ‘burr’. The burr, which gives drypoint lines such a sumptuous velvety look, wears away quickly. As a result, the decorative effect of the technique diminishes and the representation becomes increasingly lighter. Here Rembrandt solved that problem by making areas of shadow darker again with extra lines, for example under the dog in the foreground.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

When you scratch a line in an etching plate, it produces a small raised edge called a ‘burr’. The burr, which gives drypoint lines such a sumptuous velvety look, wears away quickly. As a result, the decorative effect of the technique diminishes and the representation becomes increasingly lighter. Here Rembrandt solved that problem by making areas of shadow darker again with extra lines, for example under the dog in the foreground.