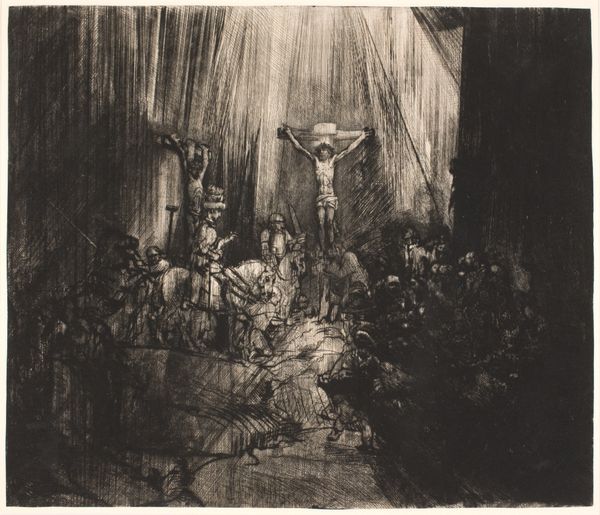

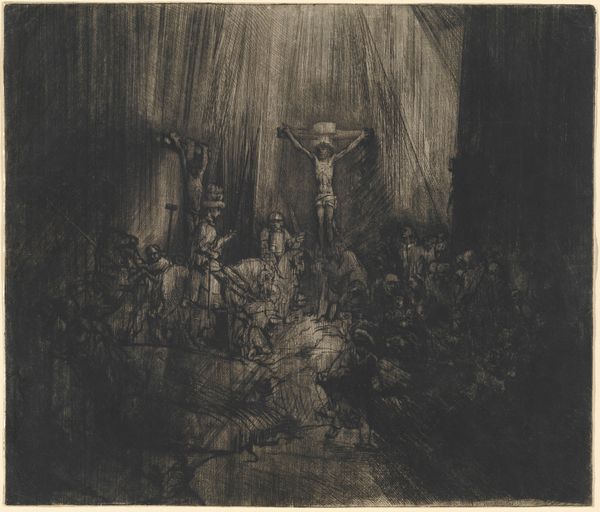

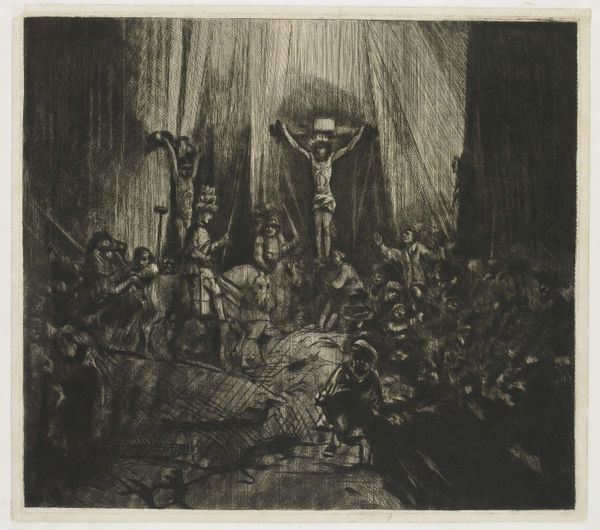

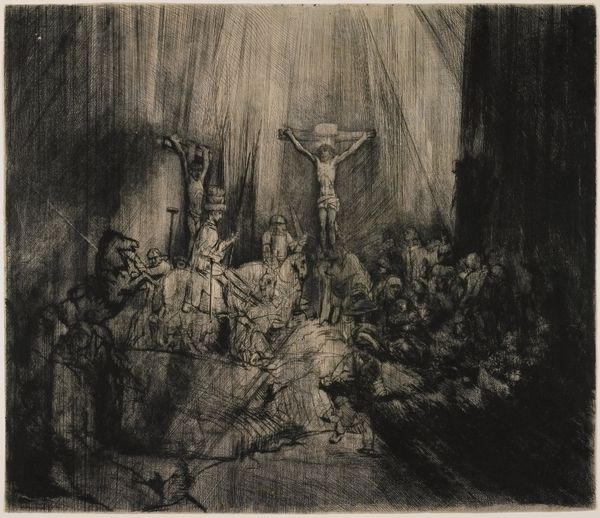

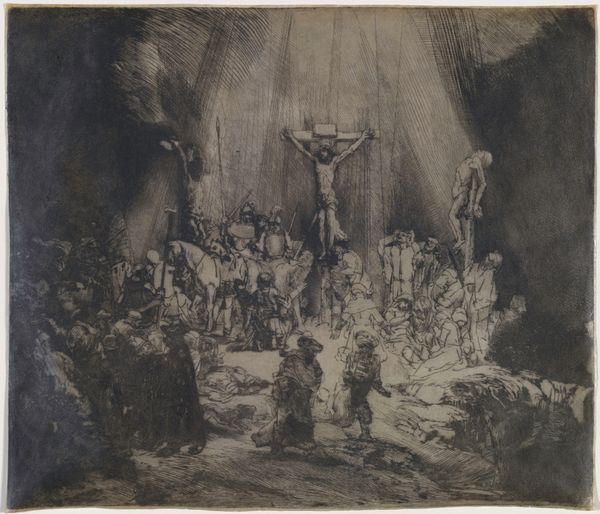

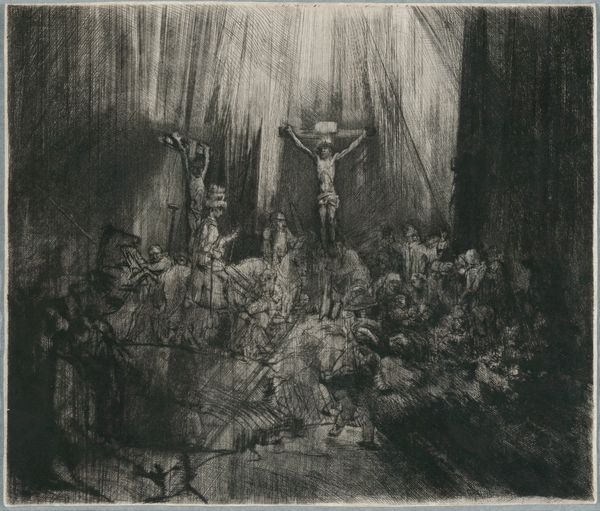

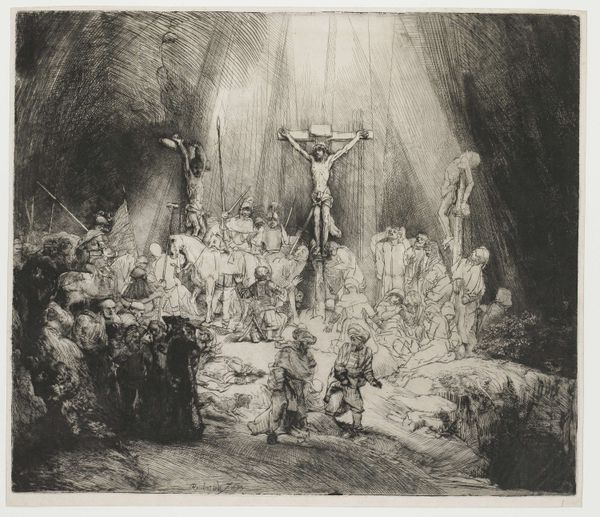

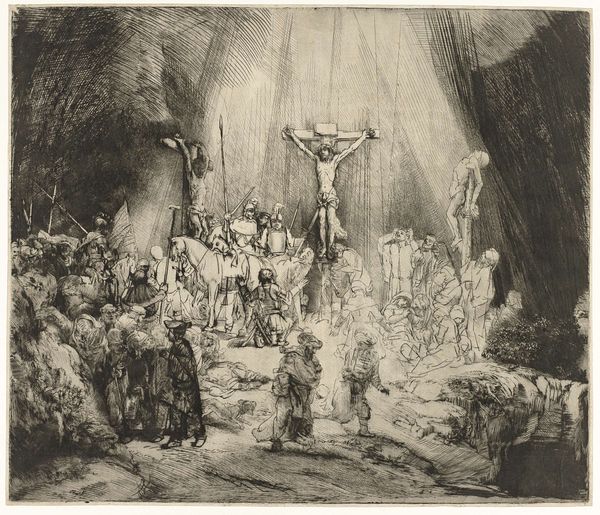

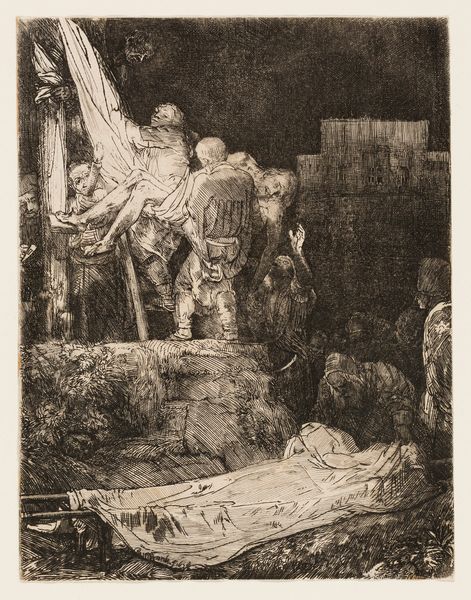

Christ Crucified Between the Two Thieves (The Three Crosses) 1653

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, charcoal

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

men

#

crucifixion

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

christ

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before Rembrandt van Rijn’s dramatic etching, “Christ Crucified Between the Two Thieves,” also known as “The Three Crosses,” created in 1653. It’s a piece brimming with complex layers. Editor: Layers is right. My initial feeling? Overwhelmed, but in a good way. Like a storm cloud gathering—you sense the immense weight and impending…something. What strikes me most is the raw emotional intensity. Curator: Rembrandt's unique rendering of this iconic biblical scene diverges quite a bit from its contemporaries, yes. In it, you can feel the socio-political unrest of the Dutch Golden Age filtering through a deeply personal lens, a society grappling with wealth, religion, and the ever-present spectre of mortality. Editor: I can feel that weight. And look at his use of light and shadow. It is masterful. See how light focuses on Christ while everyone else sort of recedes into this dark, ambiguous mass of humanity. Is it deliberate or an attempt to find his inner world as an older man? Curator: Absolutely. It emphasizes Christ's isolation, while also subtly commenting on the ambiguity of moral authority. Look at the riders, who are cloaked in darkness. Note also the printmaking technique he utilizes that suggests that. Etching, with its capacity for intricate lines, allowed Rembrandt to build layer upon layer of emotional meaning. Editor: It feels more like an expressionistic outburst than a calculated exercise. The scratching marks—raw nerve endings made visible. It looks like the feeling and emotion in the etching had to fight to get out of the copper! Curator: Some have even called his mark making, and how that lends itself to capturing a specific spiritual experience within a historical context revolutionary in his own time and something many great etchers who came after have drawn from. Editor: That raw energy still pulsates even now. When you approach art from an historical perspective as you do, it is something many art-lovers can forget. A person feeling that energy centuries after the image was wrought in that copper! Curator: And that is where a modern understanding is essential to how art should be viewed in the public square. How does the past inform the present, even here in our shared viewing experience? Editor: Something that has not changed, which you need an etching to remind you of—a work that almost seems like the art's inner emotional state. You stand here to experience and to then know it again in your own soul. I'd say that has worked on me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.