print, etching

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

history-painting

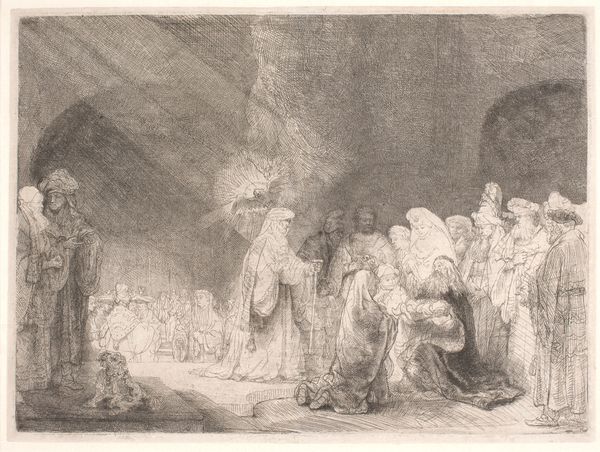

Dimensions: height 214 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

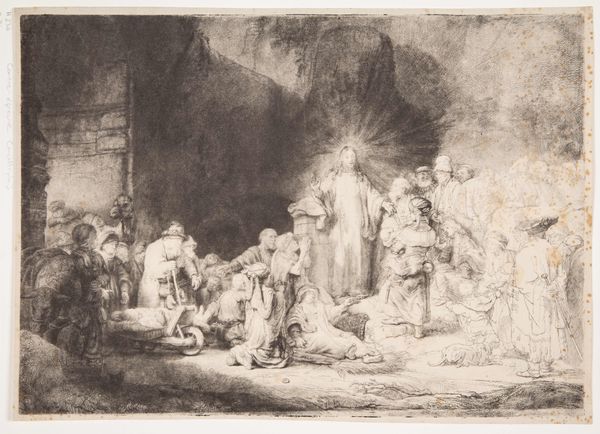

Editor: This is "The Presentation in the Temple: Oblong Print," an etching by Rembrandt van Rijn from around 1640. It's a pretty detailed scene, especially given it's a print. What strikes me is how the light is used to focus the eye on the central figures, yet the surrounding areas appear dark. How do you interpret this work, and what do you see in terms of its materiality and production? Curator: The process of etching itself speaks volumes here. Consider the labor involved in creating the copper plate, the precision required to apply the acid resist, and the physical act of etching itself. Rembrandt’s mastery allowed for the mass production of images. This brings us to a key question: how did the reproduction of images like this, make sacred narratives accessible to a wider audience beyond the traditional elite patrons of art? Editor: So, you’re saying the etching process allowed for broader distribution of religious scenes. It's fascinating to consider the print not just as an artwork, but as a means of disseminating ideas. How do the materials inform this reading? Curator: Exactly. Copper, acid, and paper – these aren't precious materials in the same way as gold or marble. Rembrandt elevated printmaking, which traditionally would have been considered craft, through both skill and production. He’s also challenging the idea of the unique artwork by embracing a process of reproducible distribution. How does this inform the way that we approach art's accessibility? Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn't fully considered. Seeing it as a shift in both art and manufacturing, and in accessibility and labor challenges what I thought I knew about art from the Baroque period. Curator: Indeed. Considering materiality challenges how art is created, viewed and disseminated within a society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.