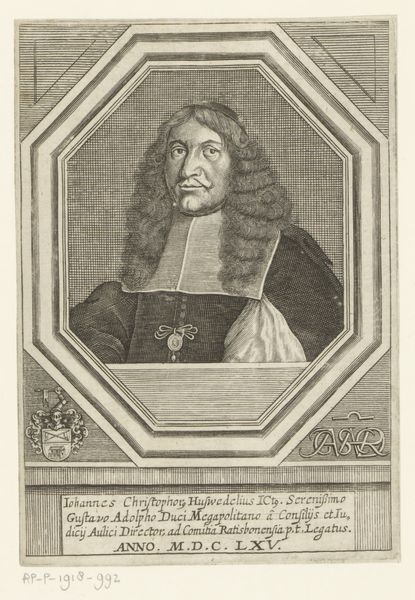

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

graphic-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 92 mm, height 142 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Pieter van Gunst's "Portrait of Urbanus Chevreau", sometime between 1659 and 1731. It's an engraving, currently at the Rijksmuseum. The intricacy of the lines creating the textures of his hair and clothing is really captivating. What strikes you about this work? Curator: The portrait exists because of labor. Someone had to physically incise those lines into a metal plate. What kind of social relationships made this possible? Who was Chevreau? Who was Van Gunst, and why did he produce this image? The texture you admire comes from skill developed over time – an investment of the engraver’s energy in producing images, in other words commodities. Editor: So you're thinking about the work that goes into creating a print like this. How does that understanding shift how we see it? Curator: It reveals the choices inherent in reproduction. Van Gunst chose to depict Chevreau this way; someone determined this image had value to disseminate. Why choose engraving? What kind of audience are we talking about? The materiality – the ink, the paper, the lines – makes visible social, economic and even intellectual networks that circulated around this portrait. Editor: It makes you wonder who would buy it and how it was used, like as part of a book? Curator: Exactly. Think of the print shops, the sellers, the consumers… What function did portraiture serve? Was it a memorial, an advertisement, or something else entirely? Editor: I guess I had only considered the artistic merit, but thinking about the "who" and "how" makes it much more meaningful. Thanks for showing me the materiality and labour. Curator: Absolutely. Focusing on production transforms the way we think about this historical depiction, giving it new significance and meaning today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.