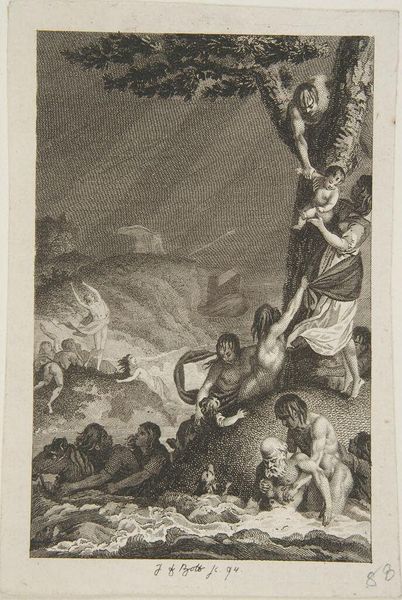

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 189 mm, width 124 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

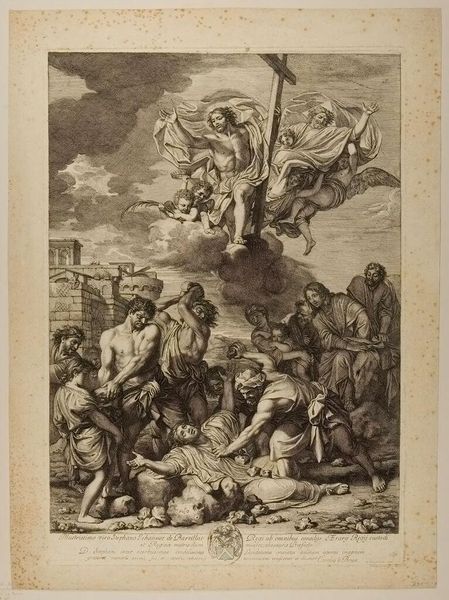

Editor: This print, “Aeneas wil het lichaam van Pandarus redden” by Bernard Picart, dating to 1710, depicts a scene of conflict and rescue. The dense composition and sharp contrasts in the engraving create a dynamic, almost chaotic effect. What stands out to me is the focus on physicality—the struggling bodies and the looming stone. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the production of this image. Consider the labour involved in creating such a detailed engraving in the 18th century. It's a reproductive medium, designed for wide circulation. How does that affect its value as a historical object? We see the materiality not just in the depicted bodies, but also in the physical process of creating and disseminating these narratives. The means of distribution, that entire system, shapes meaning. Editor: So, the act of printing and distributing the image is part of the story? Curator: Exactly. And let’s look at the subject matter, rooted in classical history and mythology. Baroque art frequently references these stories, but it's important to consider what a scene of this sort might signify in 1710. Who were the consumers of such imagery, and what role did these classical narratives play in shaping their worldview? Consider also the economy of engraving itself—who commissioned it, how were the engravers compensated? It brings us to a discussion about how art intersects with early capitalism and power dynamics. Editor: I never thought about the economics of art production so directly, that’s quite eye-opening! Thanks. Curator: Thinking about these production details allows us a deeper reading beyond the surface narrative. Considering the relationship between labour, materials, and audience changes everything.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.