metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 52 mm, width 41 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

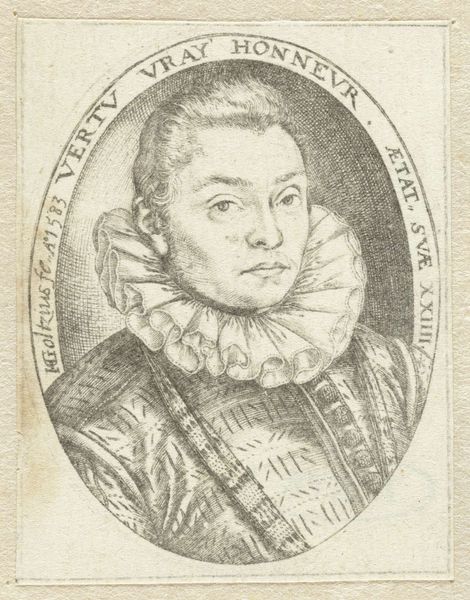

Curator: Let’s consider this Northern Renaissance engraving, "Portrait of a 24-Year-Old Man," created by Hendrick Goltzius in 1583. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I am struck by the formality of this young man. There’s an air of restrained power, but the intense details created by the engraver, particularly in his ruff, suggest a carefully constructed performance of status. Curator: Absolutely. We need to think about the context. Goltzius was a key figure in Northern Mannerism, and portraiture during this period functioned as more than just a likeness. It signified social standing and idealized attributes. What messages do you see this portrait conveying? Editor: Beyond social standing, there is an interesting intersection of identity and representation in his somewhat melancholic gaze. Is it simply an artifact of the era or are there underlying psychological complexities Goltzius sought to capture or perhaps subtly critique? Moreover, what kind of societal pressures are projected onto men, compelling a performance that borders the theatrical as indicated by the costume and affect? Curator: That’s perceptive. While Goltzius’ technical virtuosity is evident in the minute lines of the engraving, let's think about patronage and artistic license. Engravings like this were often commissioned, so we have to wonder who he was and how much control they exercised in the portrayal. It begs the question about public imagery's role in early modern society. Editor: This opens an exciting avenue for thinking about art in relation to cultural politics, right? Who had access to representations of power? How might the burgeoning middle class have been engaging with depictions such as these, emulating them? These portraits may offer critical clues for reconsidering questions about gender, social hierarchy, and self-fashioning in this period. Curator: I agree. Seeing this engraving within that broader social narrative is critical. Thank you, it truly gives a glimpse into 16th-century cultural attitudes. Editor: My pleasure, exploring those connections is where these images truly come alive for me.

Comments

rijksmuseum about 2 years ago

⋮

The commissioner of this medallion probably received a number of prints of it, which he could give to friends and family. More impressions could be pulled later. The inscription in the print appears in reverse, indicating that the medallion was made as an object in itself and not primarily as a printing plate. It was more important that the text on the medallion be legible.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.