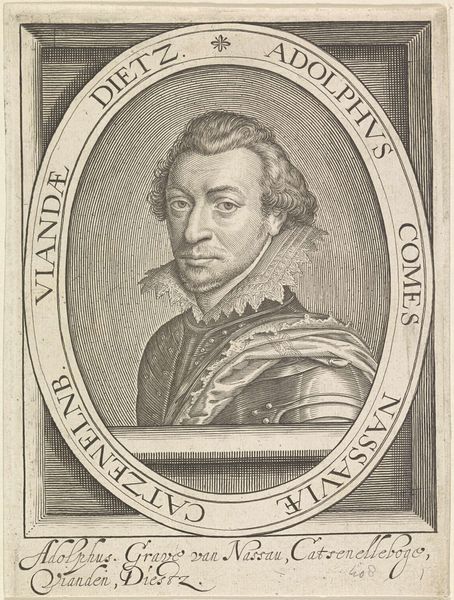

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

coloured pencil

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 181 mm, width 123 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have an engraving from somewhere between 1605 and 1699, "Portret van Adolf, graaf van Nassau-Siegen," whose artist is listed as anonymous, housed in the Rijksmuseum. The detail is astonishing. I find myself wondering about the sitter - his expression seems almost melancholic, defiant even. What do you make of this piece? Curator: The piece presents an interesting study in the construction of masculinity and power during the Baroque period. Adolf's armor isn't merely protective gear; it's a carefully constructed symbol of authority. It invites us to consider how identity was performed through dress and portraiture in this era. What sociopolitical narratives do you think the “House of Orange” alluded to above the portrait speaks to? Editor: Well, knowing that the House of Orange played a significant role in the Dutch Revolt, I'd say it implies a certain… rebellious spirit? Perhaps an alignment with ideals of independence and self-governance? Curator: Exactly! And within the context of the 17th century, it also invites conversations around colonialism and its impact. Understanding the relationship between European powers and colonized regions provides critical context, so how might this inform our reading of Adolf's portrait, beyond simply its aesthetic appeal? Editor: I guess it challenges us to acknowledge that even seemingly straightforward portraits like this can be loaded with complex histories, hinting at global power dynamics? Curator: Precisely. It becomes an entry point into discussing issues of social justice and equality, prompting critical engagement with the past and present. It underscores the importance of intersectional analysis in interpreting historical artwork. Editor: I hadn't considered how much these older works could speak to contemporary discussions, that's fascinating. Thank you for sharing your perspective. Curator: My pleasure. I believe that we all have a responsibility to critically re-evaluate historical narratives. Only in doing so, can we shape more inclusive understanding of art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.