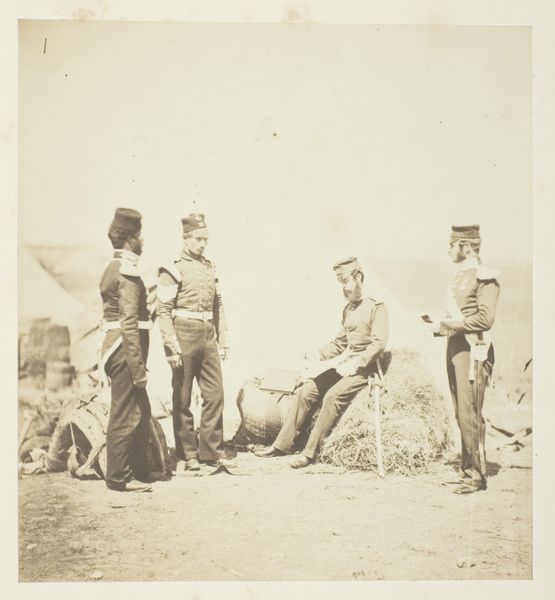

print, daguerreotype, paper, photography

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

war

#

daguerreotype

#

paper

#

photography

Dimensions: 18.2 × 15.6 cm (image/paper); 58.9 × 42.5 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

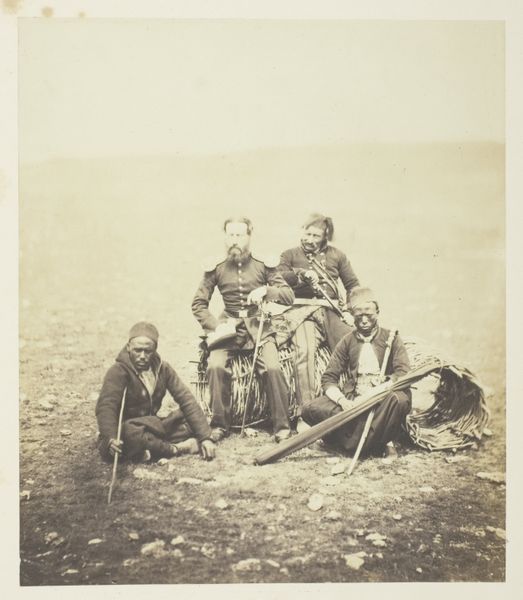

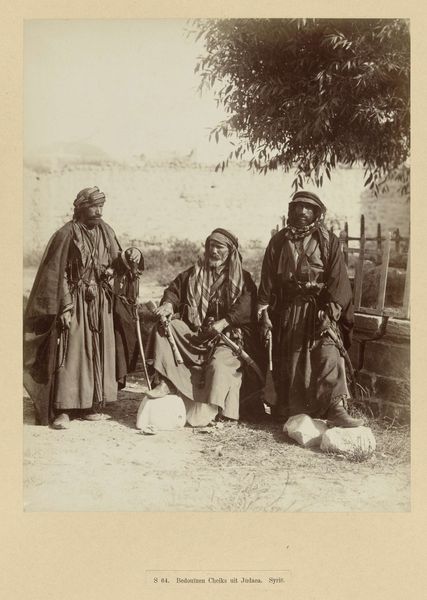

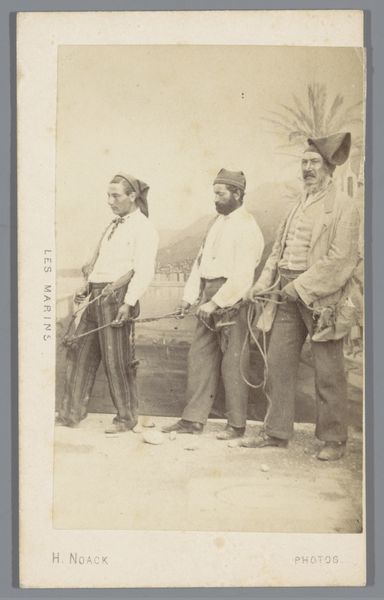

Curator: Let's turn our attention to Roger Fenton’s 1855 print, "Ismail Pacha and Attendants," currently residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It’s a somber scene. The tones are muted, almost bleached. There's a feeling of stillness, a kind of waiting…or perhaps post-conflict fatigue etched into their posture. Curator: The photograph was taken during Fenton's time documenting the Crimean War. Note the starkness of the landscape; it becomes a character in itself, speaking to isolation and the harsh realities of war. Ismail Pacha, a high-ranking Ottoman official, is the central figure. Observe the symbolism woven into their attire—the various fezzes, sashes and weapons—each hinting at power, status and cultural identity. Editor: I’m struck by what he’s seated on— a coil of rope or possibly fencing? It is a rather crude and uncomfortable-looking throne and material marker which creates such a striking contrast against his ornate clothing. It’s utilitarian, a visual interruption of the expected portrait of power. The choice and accessibility of material speaks to Fenton's constraints on site. Curator: Precisely. Fenton had to deal with the limitations of photographic technology at the time. Wet collodion process needed immediate development after the photograph, demanding the usage of mobile darkroom during documenting wars. The print is more than a depiction; it's a cultural artifact of the period—a product shaped by political events. The two attendants present further points of connection to status; their attire, their proximity to Pacha himself becomes an index of relational power. Editor: So, we have this incredibly meticulous process used to capture what appears to be a moment of complete stasis amidst chaos. What stories could those hands tell? Whose labour generated the garments adorning the officials? How long did these individuals need to stand still for a successful exposure given limited technology in production? The materiality really pulls you into a wider historical conversation, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely, and it is the photograph itself becomes a symbol, solidifying memory while it obscures aspects of experience due to technological limits. Editor: Examining the making illuminates what has been inherited culturally. I had initially interpreted weariness. Curator: But now you see…? Editor: A complex image speaking to many histories via materials. Curator: A symbol indeed, materialized for interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.