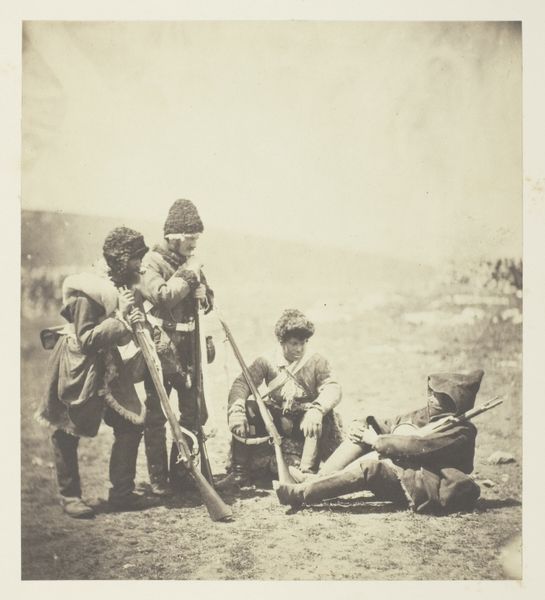

Dimensions: 18.2 × 15.6 cm (image/paper); 58.9 × 42.5 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

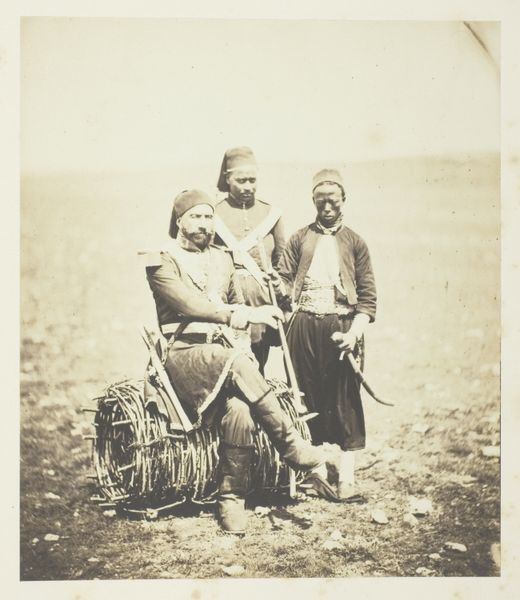

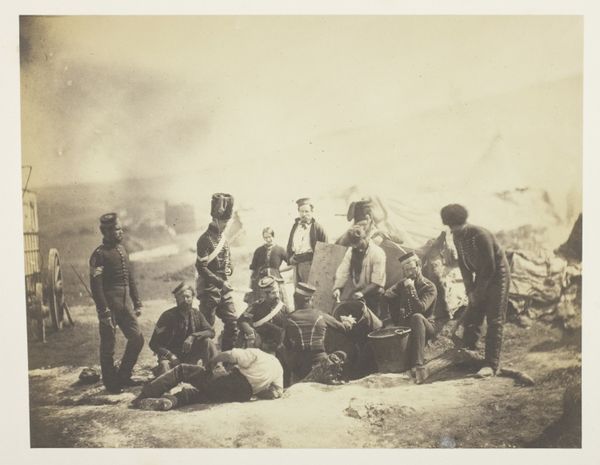

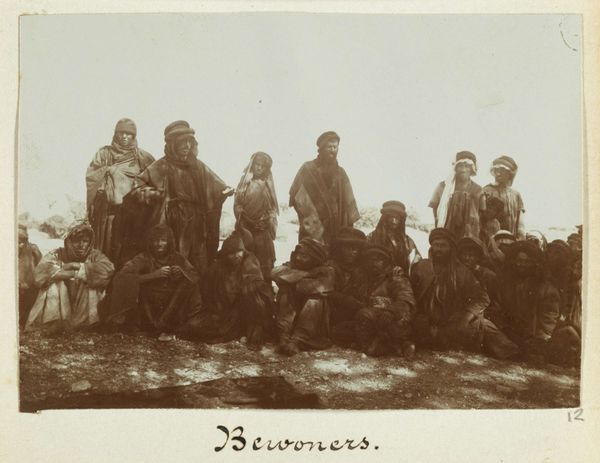

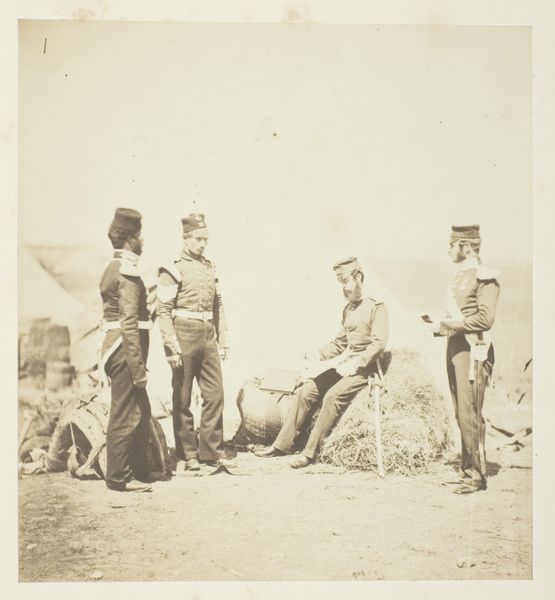

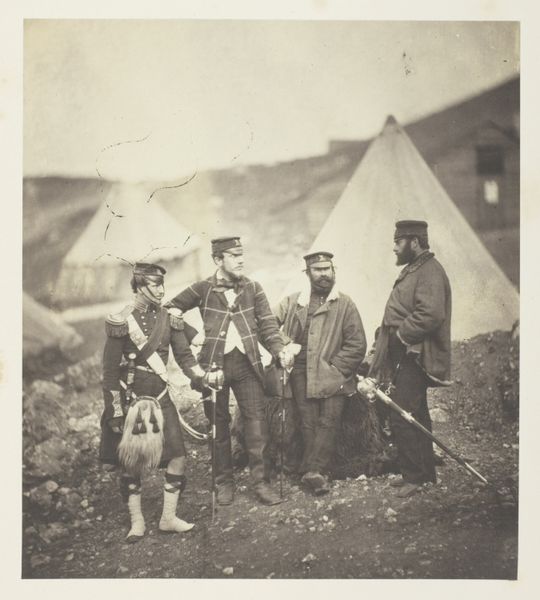

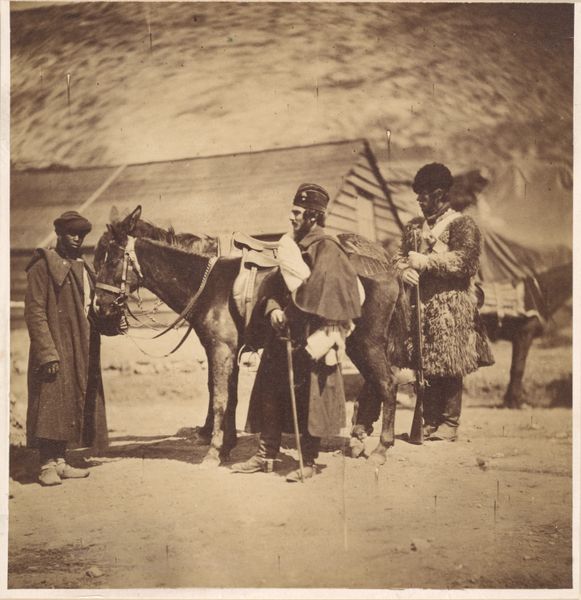

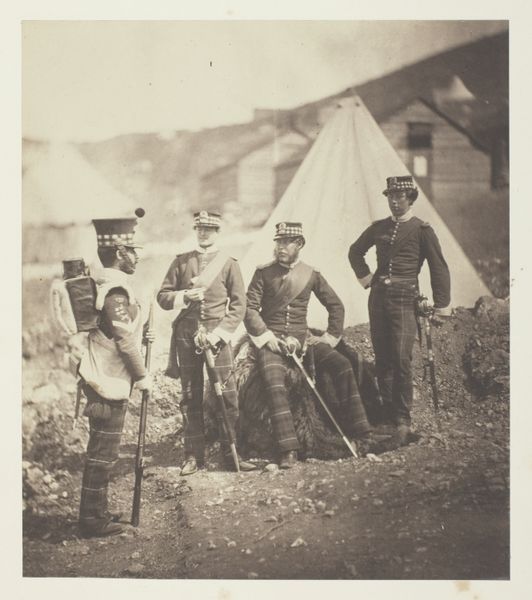

Curator: Here we have Roger Fenton’s photograph, simply titled "Untitled," from 1855. It's a gelatin silver print. What’s your first take on this piece? Editor: It feels desolate, almost staged, like a troupe pausing mid-performance in a bleak landscape. There’s a palpable weariness etched on their faces, a stoicism against… what exactly? Curator: Fenton was one of the first war photographers, capturing images of the Crimean War. He was commissioned by the British government, but it’s interesting to note the sanitized nature of his work; absent are the brutal realities and trauma of war that intersectional perspectives challenge us to consider. Editor: Precisely. What is visible then are the vestiges of military endeavor and perhaps the dawn of some strange colonialism as men of obvious privilege are posed, whilst surrounded by locals presumably pressed into roles, too. It becomes not so much about the battle itself, but the theater *around* the battle, right? How the British presence impacted those present. Curator: Indeed. The composition reinforces that distance; the expanse of empty space isolating these figures and the equipment they use from a home to which they may or may not return. It presents a constructed narrative meant for a British audience back home. This, I think, plays into contemporary understandings of national identity during the rise of the British empire and how its exploits were communicated home. Editor: And consider the print medium itself. Photography was relatively new then, creating a sort of documentary "truth." The socio-political context shapes the public’s understanding and expectations of photographic "evidence", a dynamic that resonates today in our visually saturated world. The fact of the photographic endeavor itself – where to stand? How to pose? The technical capacity for staging versus candid shots? - creates an entire narrative on its own. Curator: Fenton's photograph prompts questions about the agency of the subjects depicted. How can we interpret their stories through a postcolonial lens and what narratives of identity and power are revealed? Editor: Thinking about the photograph’s function reminds me that how an image circulates and who has access to it powerfully shapes the messages that ripple outwards. I am thinking in this case especially, of its accessibility in public museum holdings such as at the Art Institute of Chicago. It allows modern audiences an understanding of a historical point of view and from there we can use it as a jump off point to create a greater public dialogue.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.