drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

Dimensions: sheet: 15.5 x 6.4 cm (6 1/8 x 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

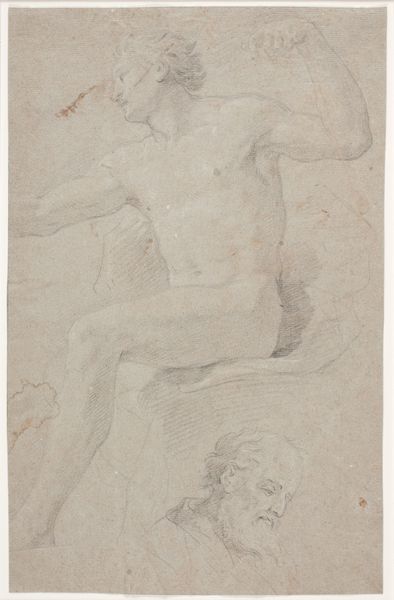

Editor: This is Raphael's "A Standing Male Nude," a pencil drawing from the Renaissance. I'm immediately struck by the dynamic pose and how unfinished it seems, almost like a snapshot of a body in motion. What can you tell me about the context in which this drawing was made? Curator: It's fascinating how you perceive the sense of movement. Remember, the Renaissance saw a resurgence of interest in classical art and the human form. Drawings like these weren't always intended as final artworks. They often served a crucial public function. Editor: What do you mean by a "public function?" I thought it was just a sketch! Curator: Think about it: how did artists in the Renaissance, especially those like Raphael who were involved in large-scale public works such as the Vatican frescoes, develop their compositions? They used these drawings as studies. They served as explorations of anatomy and pose, but also, in a more subtle way, they affirmed certain ideas of masculine beauty. In a deeply religious and often repressed society, displaying male strength and physical perfection in this way had both aesthetic and political implications. It was, in some sense, a celebration of human potential endorsed by the institutions commissioning the work. Does this challenge how you view the image now? Editor: Absolutely. So it wasn't just an artist exploring form; it was contributing to a wider visual culture shaped by specific values. I always thought about the individual artist, but I can now see how his art plays into societal ideals. Curator: Precisely. It's a good reminder that even sketches aren't created in a vacuum. We need to consider who was commissioning the work and how such an image functions in society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.