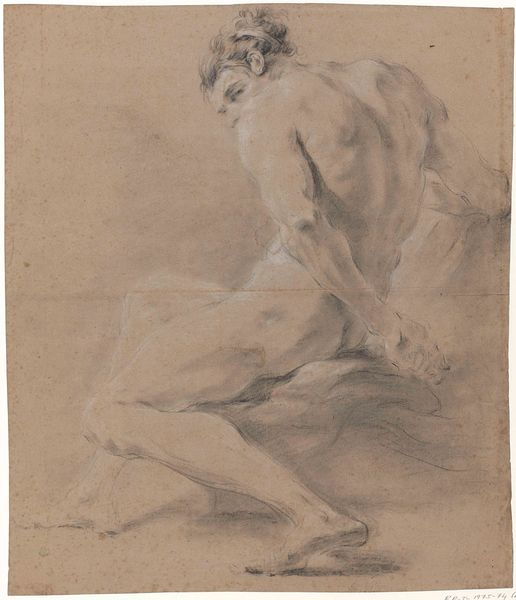

drawing, dry-media, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

dry-media

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: height 302 mm, width 213 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

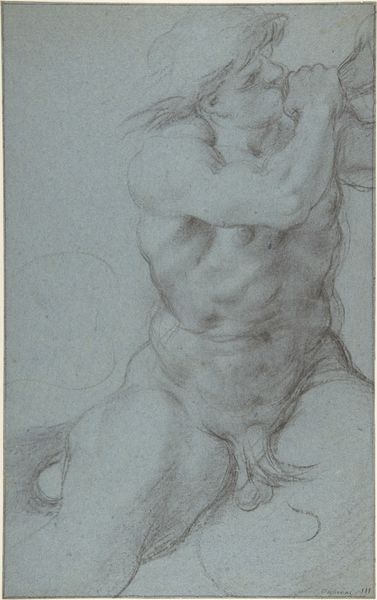

Curator: This drawing, "Studie van een naakte man met opgeheven been", which translates to "Study of a naked man with a raised leg," is attributed to Christiaen Gillisz. van Couwenberg, dating from between 1605 and 1695. It's rendered in pencil. Editor: My first impression is strain and exertion. Look at the tension in the figure, pushing, reaching—it's a study in effort. You can almost feel the grit of the pencil on paper creating that impression. Curator: Absolutely. It speaks to the academic tradition, where the male nude was a cornerstone for understanding form and ideal proportions. This wasn't just art; it was anatomical study, reinforcing social ideas about masculinity and strength. Editor: I’m drawn to the physicality of it. The repeated strokes building up the shadows, you can almost feel the artist circling the form, working the material, wrestling with the representation of muscle and bone. What kind of paper do you think he was using? The weave seems crucial to the overall texture. Curator: Considering the time period, likely a linen-based paper, readily available, and lending itself well to detailed work. But the question of "readily available" brings up interesting aspects about production itself, no? Who had access, how were these materials used, what sort of academy could support the artistic making in general? Editor: Precisely! These drawings, although preparatory, embody a network of labor—from the making of pencils and paper to the model compensated for posing. And its afterlife of ownership. Consider how many hands touched this work from the artist, to the atelier to eventually a collector, influencing taste and valuation, and ending its days hanging in some institutional vault. Curator: An astute point. It's easy to forget that artworks are also commodities. This study wasn't simply an exercise, but a piece that circulated, influencing aesthetic standards and reflecting societal power dynamics of patronage. These materials also represented an artist who might or might not have received the sort of patronage that sustained one’s household. Editor: Indeed. I keep returning to the rough quality—almost hurried. This wasn't some pristine demonstration piece. There's something honest in that lack of polish. Curator: A powerful reminder of the many lives an artwork leads. Editor: And the human labor etched within its very fibers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.