print, engraving, architecture

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

#

architecture

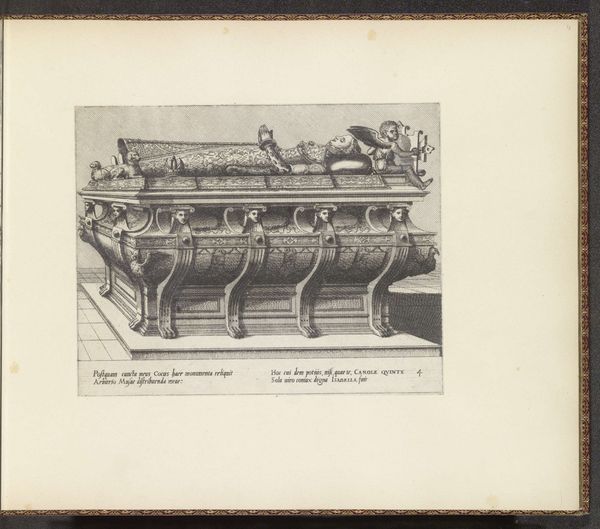

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

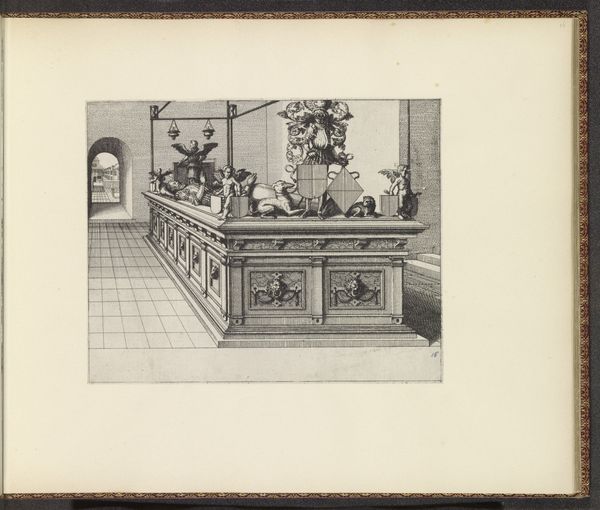

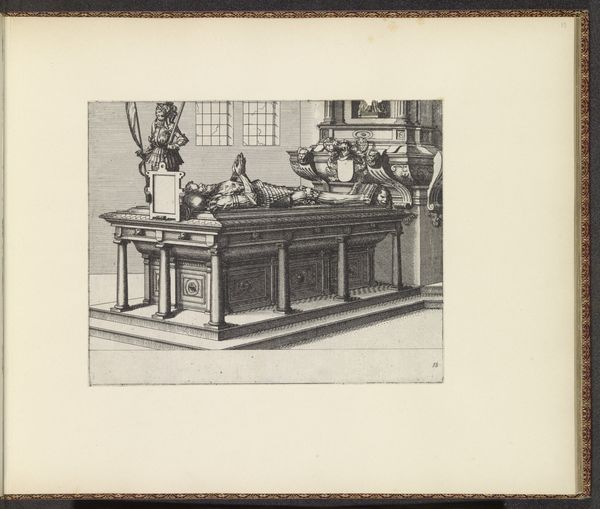

Curator: This engraving from 1563 by Johannes and Lucas van Doetechum depicts a "Freestanding Monument for a Field Commander," held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate thought is how it stages power—even in death, there’s this incredible need for commemoration and dominance made literal in stone. Curator: It’s such a complex image! The symbolism packed into this single print would have resonated profoundly in the 16th century. Look at the armored figures holding shields that surround the tomb, almost like they are forever guarding his memory and lineage. Editor: And the figure lying atop, surrounded by what look like family crests. What does it mean to perform military might and family legacy together in this way? Curator: For nobility, those things are usually inseparable. The visual vocabulary speaks of valor, duty, and above all, the continuity of family lines, preserved in history. What seems like a memorial is also propaganda. Editor: Precisely. I find myself wondering who commissioned this piece and what political motivations were behind showcasing this individual's—and family's—power in such a blatant fashion. Was it about reinforcing status during a time of upheaval or competition? Curator: Possibly. Death was certainly a theatrical affair and an opportunity for some to signal continued prominence, though this piece might have also served as a source of inspiration to other military figures. A way to immortalize the standards and virtues to which commanders might aspire. Editor: That resonates; still, considering the role of warfare and dominance, shouldn't we also interrogate how images like this potentially normalize the idea of constant military struggle and patriarchal rule? Who is excluded or harmed by this perpetual power display? Curator: That’s an insightful counterpoint, as is right given the function of these objects is usually to obfuscate. Artworks often have many, intertwined motives, all bound to their time. Looking deeper can tell us so much about history’s hierarchies. Editor: Definitely, analyzing these imprints lets us consider both what they meant then and how those meanings have persisted, shifted, or become contested across time, providing different ways to relate and resist power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.