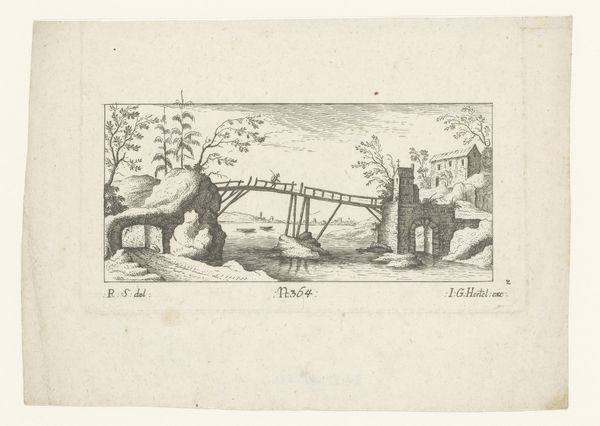

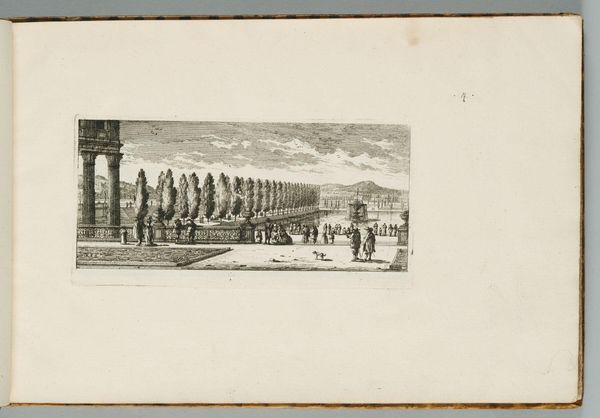

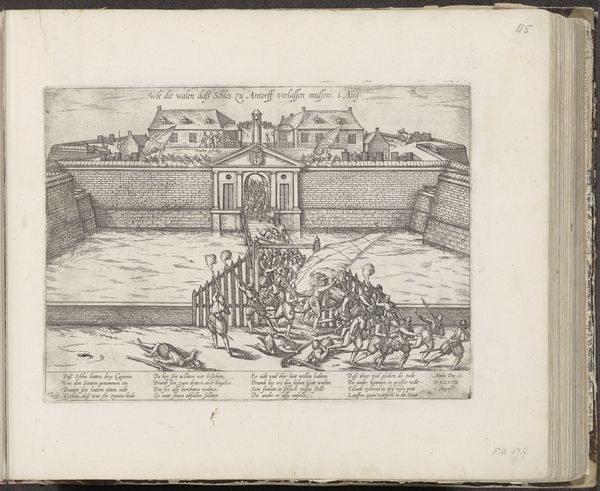

drawing, print, metal, engraving

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

metal

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

ink colored

#

line

#

pen work

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

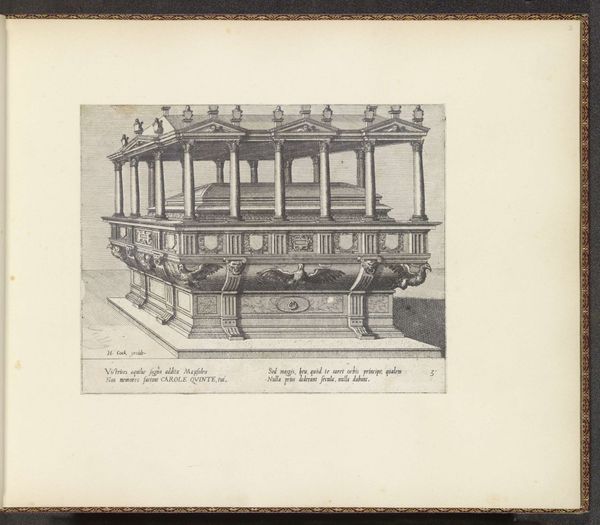

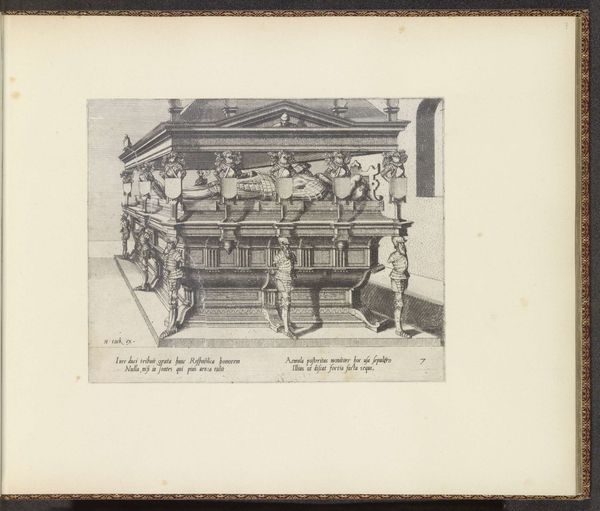

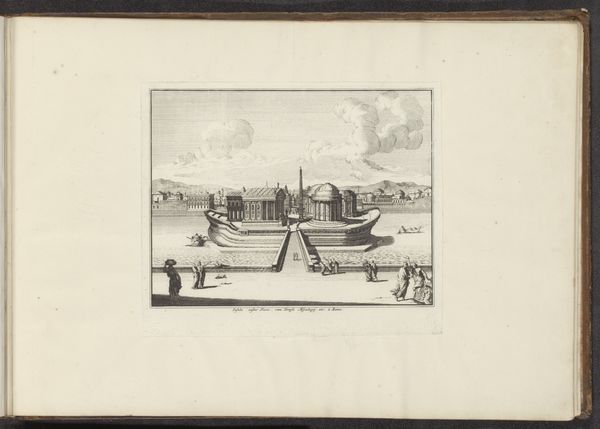

Dimensions: height 166 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

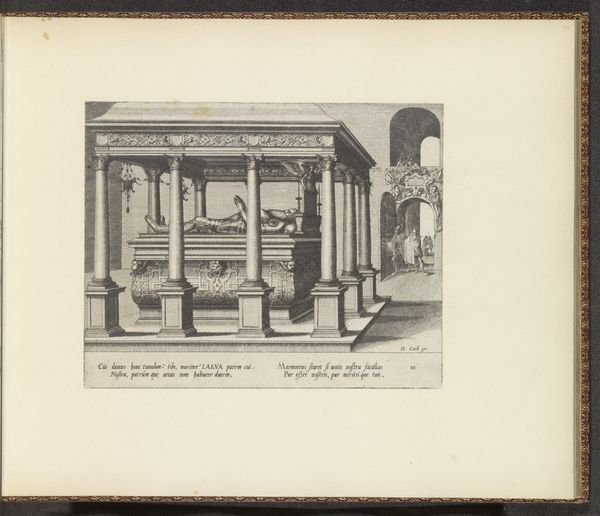

Curator: This engraving, "Vrijstaand grafmonument voor Isabella," made by Johannes or Lucas van Doetechum in 1563, presents a fascinating view of Renaissance funerary art. Editor: It's incredibly detailed, almost like a technical drawing. I’m struck by how much the monument itself looks like it’s made of metal and stone. What stands out to you most about this piece? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the materials suggested in the image and the labour involved in producing it, both the actual monument and the print itself. Think about the societal value placed on creating such elaborate tombs. The engraving isn’t simply representational; it's an act of preservation and propagation, meant to circulate and reinforce Isabella’s status. Editor: So the print functions almost as a form of propaganda then, by highlighting her status in this way? I’m curious about the choice of printmaking as a medium. Was it chosen to democratize her memory somehow? Curator: Partly, but think about who had access to prints like this in 1563. While more accessible than the monument itself, circulation would still be limited to wealthier segments of society. What is interesting here, materially, is the act of replicating grandeur through a medium like engraving, highlighting the means by which power and memory are manufactured and consumed. Editor: That makes me consider how the cost and availability of the engraving material itself – the metal plate and paper – shaped the image’s circulation and impact at the time. It connects this intimate image to broader economic realities. Curator: Precisely! Considering these details enables us to look beyond the artistic representation and toward the processes of material culture that underwrite it. Editor: It's really changed how I see engravings! Now I can better consider them as objects embedded in the social and economic fabric of the 16th century, rather than just pretty pictures. Curator: And by considering the material reality, we move closer to the original intention in propagating the image: underlining class distinctions in early modern Europe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.