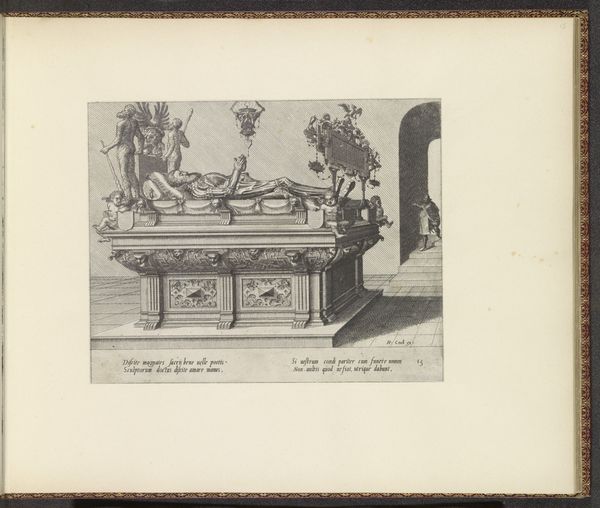

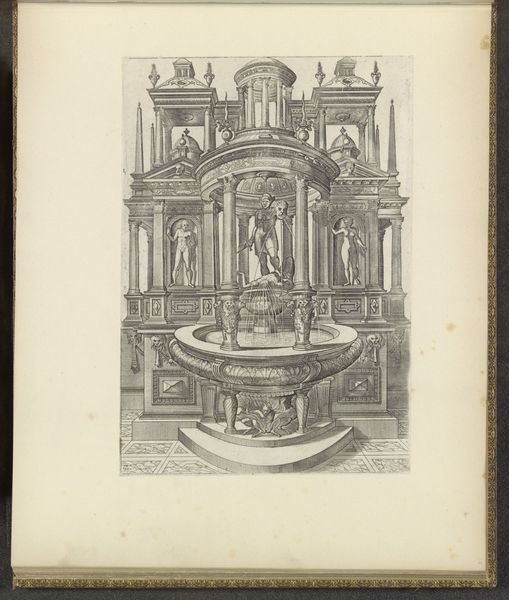

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

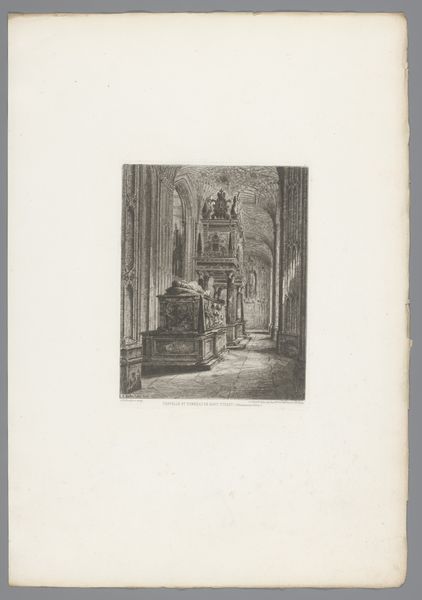

graphic-art

#

medieval

# print

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

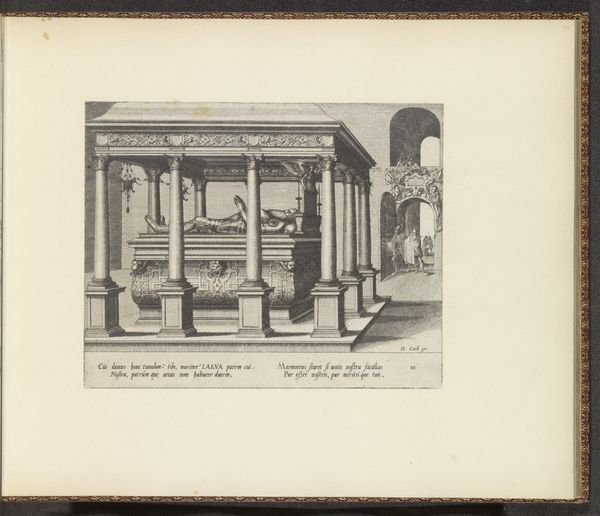

Editor: This engraving from 1563, titled "Grafmonument voor een echtpaar," attributed to Johannes or Lucas van Doetechum, shows an elaborate tomb. It has such a somber and stately mood. What social or political statements might this piece have been making? Curator: That's a perceptive question. In the Renaissance, monuments like this were explicitly tied to power and social standing. This engraving serves less as a simple memorial and more as a record of their lineage and position. Who would see such a piece, and how might that have impacted them? Editor: Presumably, other wealthy families, clergy, and perhaps even commoners who had access to the church where the monument stood. I imagine it reinforced existing social hierarchies. Curator: Precisely. The display of wealth, lineage represented by the heraldry, and the sheer scale – even captured in print – would impress upon viewers the importance and legacy of the deceased. Engravings like these allowed for wider dissemination of such imagery. This ensured that more people than just those who saw the monument in situ understood its meaning. Editor: So, the print format democratized access to the image but simultaneously reinforced an aristocratic worldview? Curator: In a way, yes. The act of commissioning such an elaborate monument and then reproducing it as a print becomes a form of cultural propaganda. It shaped public memory and served the ongoing interests of the family. It’s fascinating to consider how visual culture was actively constructing historical narratives even then. Editor: It is. I hadn’t thought about prints as a form of propaganda, but it makes perfect sense in this context. It definitely provides another lens for examining Renaissance art! Curator: Exactly! Thinking about art as a player in historical events—that's the key.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.