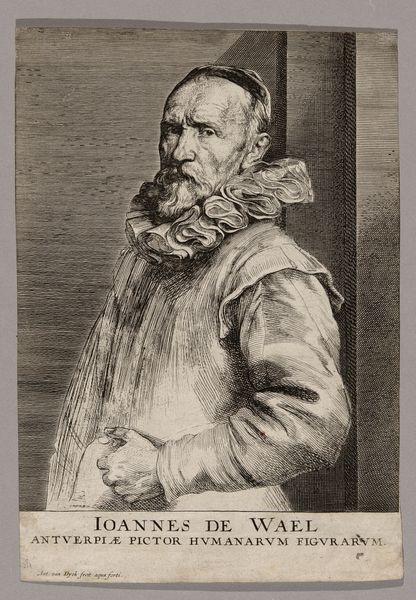

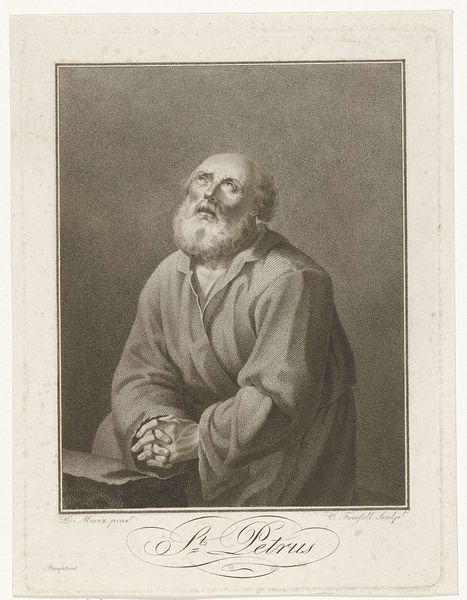

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

paper

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 250 × 178 mm (image/plate); 258 × 185 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Anthony van Dyck’s etching "Jan de Wael," dating from 1630 to 1633. It's printed on paper and held at The Art Institute of Chicago. The sitter’s face seems weathered, almost stoic, but there's also a clear element of wealth and privilege indicated by his ruffled collar. How do you interpret this portrait? Curator: Beyond a mere depiction of wealth, let’s consider how Van Dyck, through Jan de Wael’s portrait, engages with the power dynamics inherent in portraiture of this period. Jan de Wael, as a member of Antwerp’s elite, is positioned within a network of social and political power. How does the visual language of this portrait—the composition, the gaze, even the etching technique itself—contribute to or challenge prevailing notions of masculinity and status in 17th-century Antwerp? Does it align with or subvert our expectations, considering the social and political upheavals of the time? Editor: I see what you mean. The etching technique itself, with its intricate lines, almost feels like a commentary on the complexities of identity, but can you expand on the social upheavals you mentioned? Curator: Antwerp in the 17th century was a site of intense political and religious conflict. By emphasizing de Wael's individual characteristics alongside signifiers of status, Van Dyck potentially walks a tightrope, legitimizing authority whilst intimating the fragility of entrenched hierarchies. To what extent do you feel Van Dyck’s composition reinforces established paradigms of power, or perhaps subtly questions their very foundation through de Wael’s individualized depiction? Editor: I hadn't considered that tension. Viewing it now, it seems Van Dyck wasn't simply painting a likeness; he was making a statement about power and identity during a time of massive upheaval. Curator: Precisely. It prompts us to question who is seen, how they are seen, and for what purposes those visual representations are created. Editor: Thanks. Thinking about this work within the broader social and political context definitely reshapes my perspective of van Dyck’s intentions. Curator: Absolutely. By connecting art to historical context, we can reveal complex interpretations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.