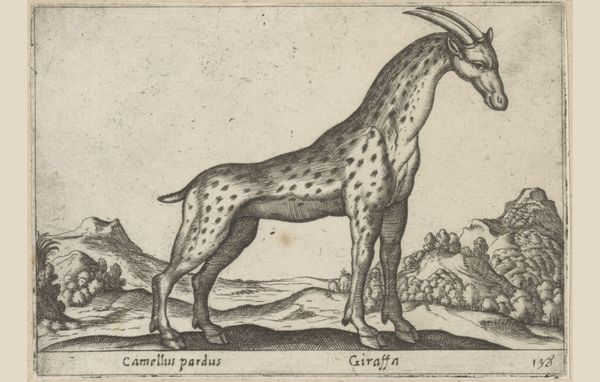

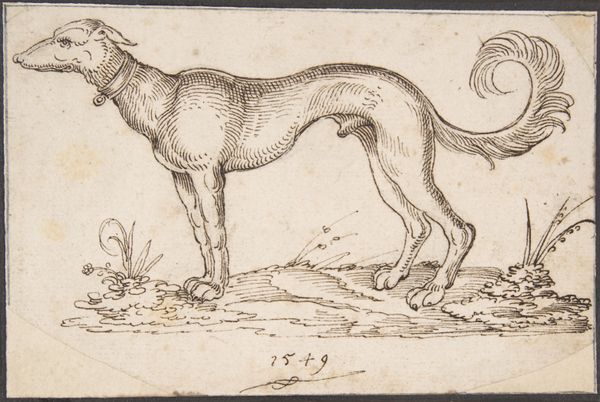

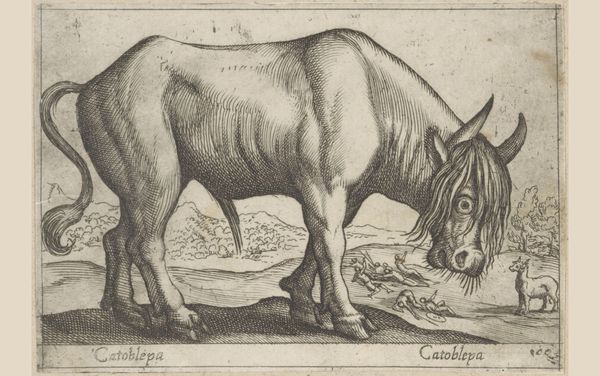

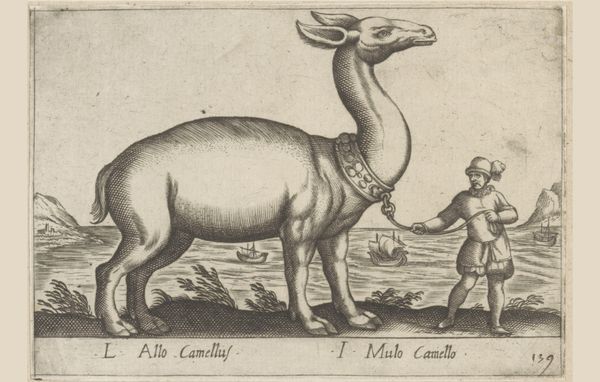

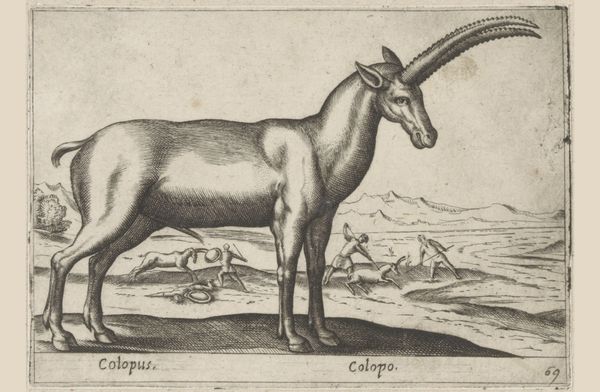

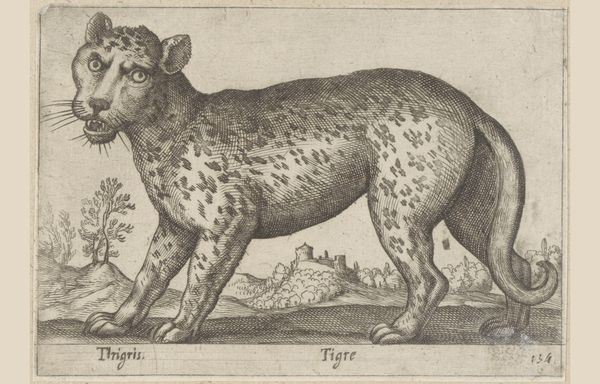

print, engraving

#

baroque

#

animal

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's discuss "Giraffe," an engraving created before 1650, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum and attributed to Antonio Tempesta. Editor: My first impression is one of slight bewilderment. It’s clearly a giraffe, but the landscape feels oddly generic, and its patterned hide seems…stylized, almost like a textile design. There's a captivating artificiality to the animal. Curator: Precisely. Context is key. These images were circulated during a period of intense colonial expansion and scientific exploration, embodying a visual means of asserting cultural dominance over the natural world. How does representation facilitate appropriation, if we consider it? Editor: Ah, now the labor comes into view. I'm considering the act of making this image. The controlled, repetitive lines of the engraving suggesting the discipline and effort required to depict this “exotic” creature for European consumption, the print as a form itself implies it had a value to share, trade or study in some material way. Curator: Absolutely, let's think about the animal within its intersectional reality. It speaks volumes about Europe's relationship with Africa at the time, where nature was seen not for its inherent worth but through a lens of potential exploitation. We have a depiction rendered to meet the desire and expectation of a Western audience. Editor: But did that Western audience notice the animal at all? The labor of representing nature, as a type of early manufacturing process, might reveal more about the socio-economic interests of those in power and less about an authentic understanding of, or a moral concern for, this particular giraffe. Curator: The way the animal is framed, in its slightly off register lines and stiff posture, hints at the broader power dynamics and gendered structures. Early scientific illustrators were always men, defining an almost godlike dominance in that act of capturing something that has freedom, placing it in a fixed and therefore weakened posture to conform to masculine identity. Editor: And what does that say about access to resources, even just copper and ink? Tempesta's ability to create this engraving positions him within a very specific socioeconomic bracket that dictated both what could be represented and, essentially, the visual language used to shape public perception. The means of artistic production reflect and perpetuate those social stratifications. Curator: Considering those historical implications makes the simple, linear forms we are now presented with into complex cultural symbols, objects loaded with implicit political messaging. What a powerful insight into cultural values that are perpetuated to this very day. Editor: Agreed, there’s much to unpack here, thinking beyond the simple rendering of an exotic animal towards the labour and structures of power invested in materialising an animal we had previously, literally, only heard rumours of.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.