Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 124 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

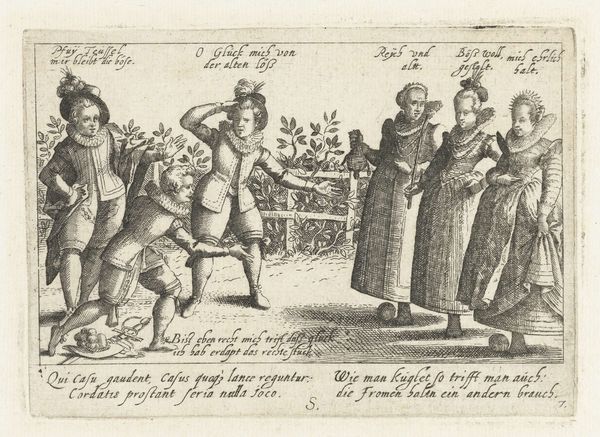

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before "Twee bladzijden met dwergen, ca. 1720," two pages featuring dwarfs, from around 1770-1780, a print created via engraving. I find the crispness of the lines really striking. What's your initial response to this image? Editor: My immediate impression is… unsettling, but intriguing. These aren’t your cute storybook dwarfs; there’s a satirical bite here, a darkness lurking behind the quaint presentation. What do you think the engraver was working toward in this period? Curator: I am fascinated by the production of these images. Note the texture achieved through the painstaking process of engraving – the deliberate strokes to create shadow and volume. Consider how the relatively low cost of printed images expanded access to visual culture at this time, playing a critical role in information and communication, especially amongst burgeoning literate, merchant, and artisan classes. Editor: Absolutely. These were clearly aimed at a particular segment of society, most likely to challenge prevailing notions of religion and honor. Look closely at the figure on the left with the scallop shells, symbolic of pilgrimage and often worn by travelers and clergy. He carries his alms purse—it feels almost accusatory to call such behaviors into question. It reflects shifts in societal values that were occurring, the erosion of traditional belief systems. Curator: Indeed, we have to recognize that the economics of printmaking influenced its aesthetic. The constraints—the labor, materials, and technical skill demanded—ultimately shaped the visual language itself. What the images represent is as much the material as the cultural context they emerged from. Editor: Precisely. Consider, for example, the dwarf on the right carrying a man in a basket. Is it commenting on cuckoldry, portraying the character as ‘Cornutus’, the cuckold or ‘the planter of horns’? Such satirical imagery served as a potent form of social commentary during this period, questioning masculinity, virtue, and power dynamics. Curator: I am stuck with how efficiently these satirical notions were propagated due to how accessible prints are to wider populations. It’s worth reflecting how these very characteristics also gave rise to caricatures used as forms of cultural bias or outright violence against already marginalized people. Editor: That's such a critical point. These images served many purposes—critical analysis, education, even just plain fun for some. Yet they also contributed to shaping narratives around others with real life consequences. This pushes me to continue questioning whose stories and viewpoints were reflected during the time and what hierarchies prevailed to decide what was made or circulated. Curator: Absolutely, thinking about access and affordability helps highlight the ways in which class shaped and influenced visual culture itself. Editor: It certainly provides much to contemplate, revealing both artistic craft and societal critiques within the strokes of its lines.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.