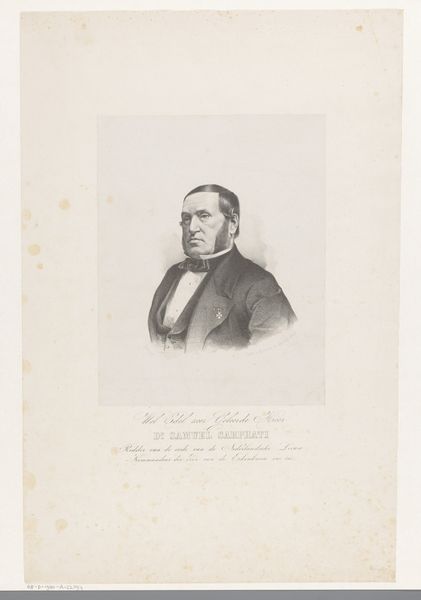

Dimensions: height 472 mm, width 373 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

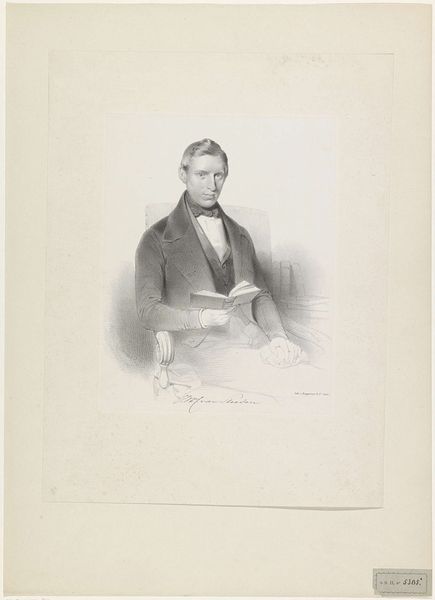

Editor: Here we have Sybrand Altmann’s “Portret van Samuel Sarphati,” placing its creation somewhere between 1832 and 1890. It's a pencil drawing. There's a stillness, a quiet dignity about him. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Considering its historical context, this portrait reflects the rising prominence of civic figures in 19th-century Europe. Sarphati was a physician and social reformer. Doesn't this formal depiction – the careful rendering of his attire, the composed pose – tell us something about the values placed on public image and social mobility at the time? What does his confident but reserved posture suggest about the relationship between public service and personal identity during the era? Editor: It's true. The pose and detail do emphasize a certain status, a place within society. But beyond that, is there a message of inclusivity or does it reflect the exclusivity of power at that time? Curator: That’s a vital question. While portraits like these can seem like straightforward depictions of individuals, they are actually carefully constructed statements. Consider who had the resources and social standing to commission or sit for such a portrait. The image might celebrate Sarphati's accomplishments, but what does it conceal about social hierarchies and the representation of other communities? Perhaps we need to examine whose stories were not being told and how the visual language of power contributed to this imbalance. Editor: So, it's not just about what we see, but also what’s conspicuously absent? It’s powerful to consider art in the context of the social narratives that shaped it. Curator: Exactly. By interrogating these portraits, we can reveal complex power dynamics and hopefully promote critical dialogues around identity and representation even now. Editor: That gives me so much to consider when viewing art of this period. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.