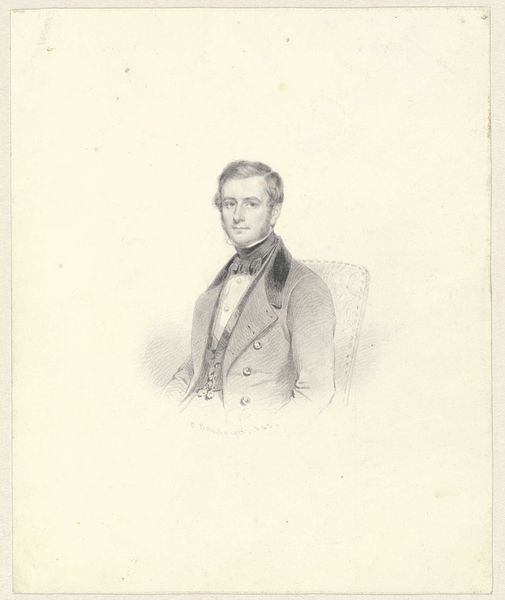

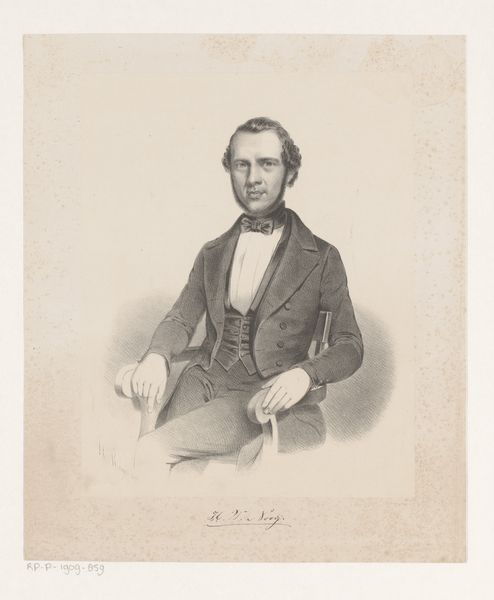

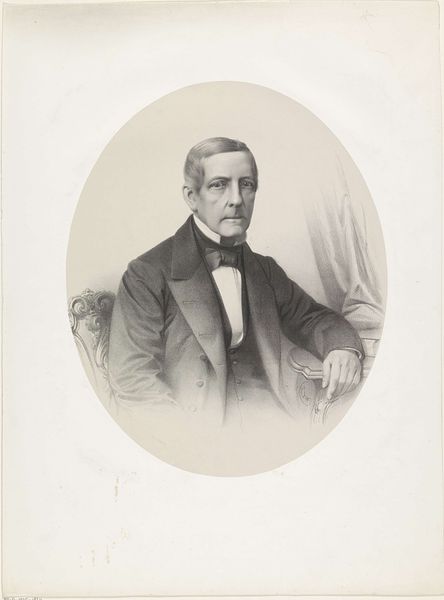

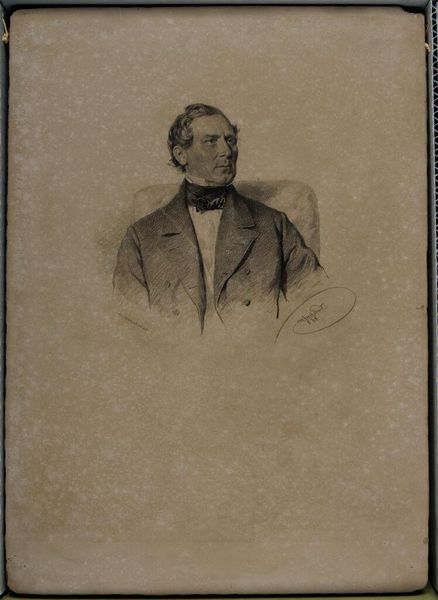

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 370 mm, width 280 mm

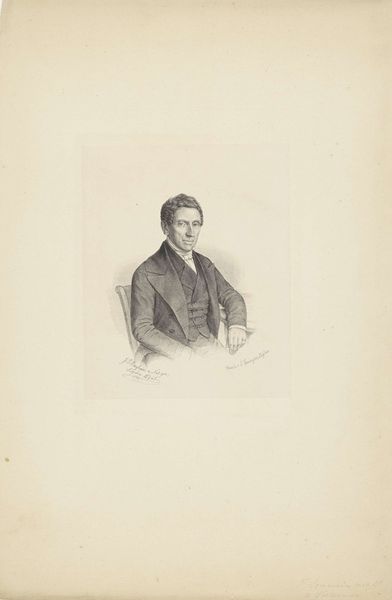

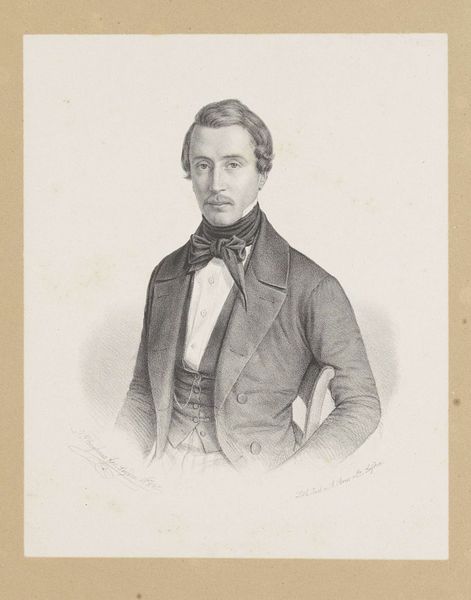

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

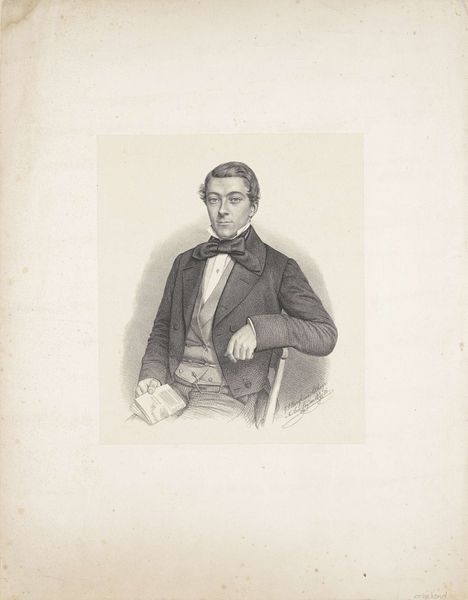

Editor: This is "Portret van J.W.C. van Steeden," a pencil drawing dating from 1832 to 1873. There's a formality to the portrait, yet the soft pencil strokes give it an approachable quality. How do you interpret this work within its historical context? Curator: The formality you notice speaks volumes about 19th-century portraiture, especially within academic art circles. These images were carefully constructed to convey status and respectability, yet this drawing invites us to look deeper. Consider the sitter’s gaze, his posture with the book...What do these elements communicate about his identity beyond his social standing? Editor: He seems engaged and intelligent, perhaps hinting at his intellectual pursuits. I imagine education was a privilege during this time. Curator: Precisely! The book becomes a symbol of access and power. Think about who had the opportunity to be literate and leisurely in those days. This portrait, then, isn't merely a likeness, but a statement about societal hierarchies. And how does the choice of pencil as a medium affect your understanding? Editor: Because it feels more intimate than, say, an oil painting? Perhaps even more accessible? Curator: Yes, exactly. Perhaps the softness is an intentional counterpoint. Wilhelmus Cornelis Chimaer van Oudendorp deliberately subverts conventions through an embrace of realism and understated presentation of status. Are there other potential conflicts? Editor: Thinking about it that way highlights some potential challenges about my own implicit and perhaps inaccurate biases. I will make a note about how that is embedded within the work. Thanks for this different insight. Curator: It’s by engaging with these very questions, these embedded tensions, that we create more equitable and representative art histories. Keep questioning those narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.