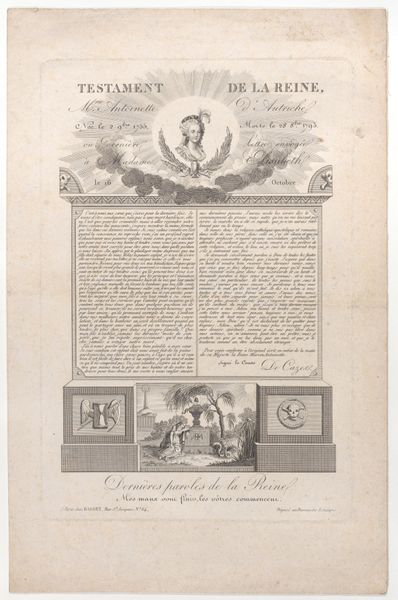

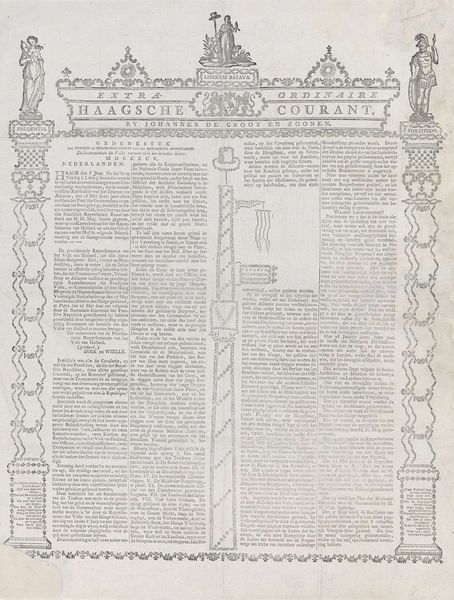

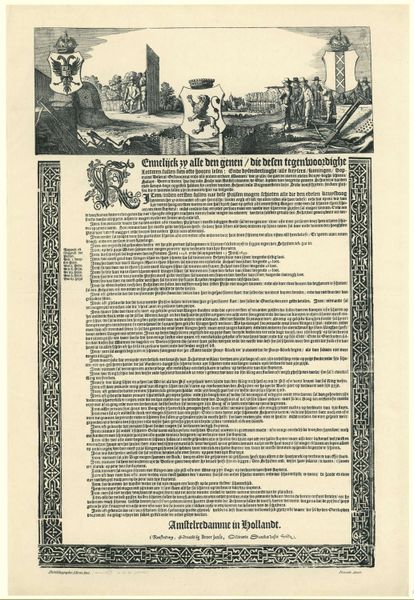

The last words of Louis XVI (Testament de Louis XVI) 1793 - 1800

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

paper

#

text

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 16 1/8 × 10 1/2 in. (40.9 × 26.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

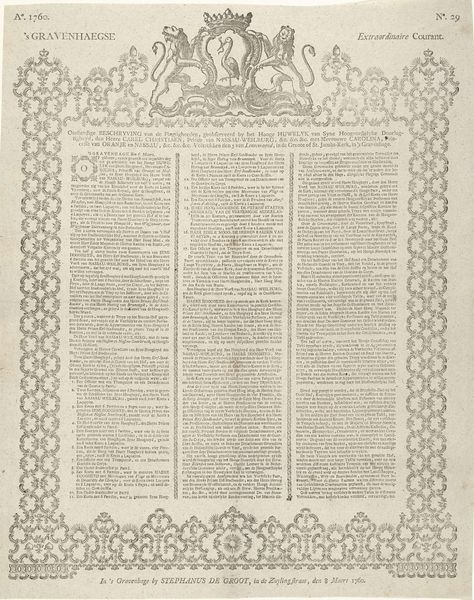

Editor: This print, “The Last Words of Louis XVI”, made sometime between 1793 and 1800, appears to be a reproduction of Louis XVI’s testament, framed by a leafy border and topped with a vignette. It feels like propaganda, attempting to control the narrative surrounding a pretty tumultuous period. What’s your take? Curator: You've rightly identified the core issue: narrative control. We need to think about the 'who' and the 'why'. Who created this print, and what socio-political agenda might they be advancing? The careful Neoclassical design and prominent placement of text over image suggest a desire to legitimize Louis XVI's legacy after the Reign of Terror. Is this an attempt to rebrand him as a martyr, to influence public opinion? Editor: A rebranding, definitely! The image above the text shows a figure slumped beside an urn, which looks to me like pretty obvious symbolism of mourning and loss. Who was the intended audience for this print? Was it for private devotion, or public display? Curator: Precisely! Now consider the historical context. In the years following the French Revolution, visual representations became powerful tools for shaping public memory. The text is legible, but is it truly accessible? It looks like this was designed for an educated elite who held power and had the literacy to decipher the text. The medium itself - a relatively inexpensive print - suggests broader distribution, but its message caters to a specific demographic, one perhaps yearning for the old order. It definitely played a role in shaping counter-revolutionary sentiment. Editor: I see what you mean. So, it is about the print operating as a symbolic object. Is there anything else in the piece's style that supports that goal of legitimization? Curator: Consider the Neoclassical style—the framing border, the idealized vignette above, that careful arrangement—it echoes earlier visual tropes associated with royalty. Think Versailles. By appropriating that aesthetic, does it subtly argue for a return to traditional authority, associating the deposed king with established ideals of order and decorum? Editor: I never would have considered the aesthetic choices as part of the propaganda machine. Looking at this work as more than just an historical document definitely broadened my perspective! Curator: Exactly! And that’s where the power of understanding socio-political history lies, helping us unpack visual culture. It is so much more than just ‘history-painting,’ and opens paths to new interpretations!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.