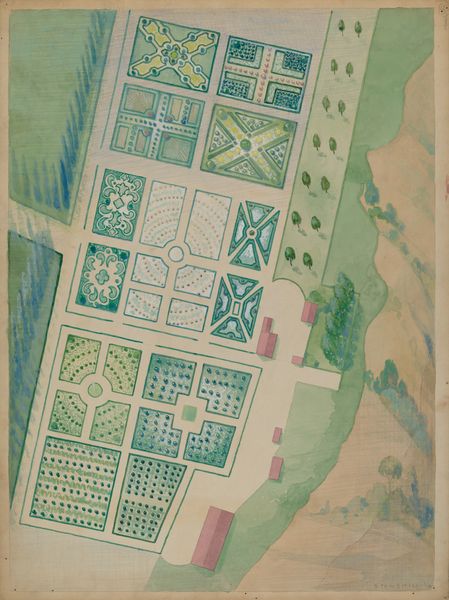

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 22.5 x 28.9 cm (8 7/8 x 11 3/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

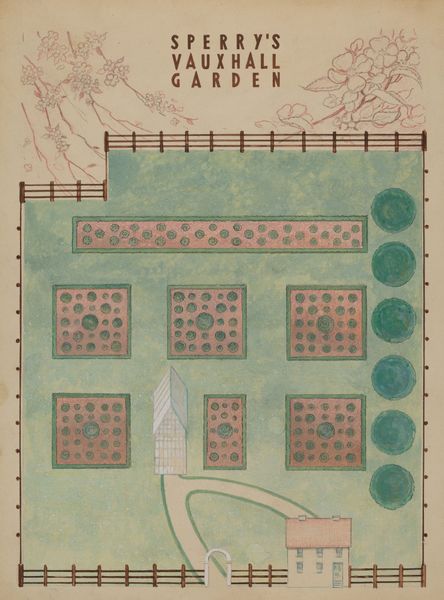

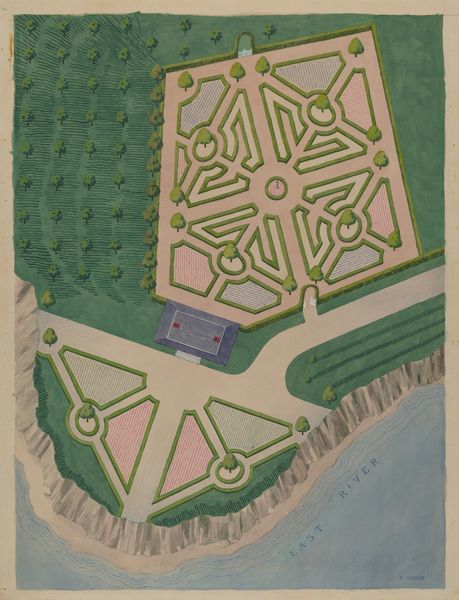

Curator: Here we have George Stonehill’s watercolor and ink drawing, "Peter Stuyvesant Garden," created around 1936. It presents a carefully laid-out garden plan. Editor: It has this kind of formal serenity that speaks to a real sense of power and control, the way everything is aligned. But something about that architectural projection in the corner also reads as fragile and incomplete. Curator: In the top register of the image, Stonehill has included a row of what appear to be sketches of fruits and vegetables. Can you read any symbolic connection between this detail and the Stuyvesant Garden plan? Editor: The planned-out fruit and vegetation motif makes me think of colonialism. This garden plan represents not just organized nature but also the imposition of European will onto American land. Curator: A cultural landscape designed by Dutch colonists, that imposition, and all that followed, certainly leaves a complicated legacy. Think about how gardens act as deliberate spaces for social gathering. How does Stonehill emphasize this purpose through geometric pattern and ordering? Editor: The rigid patterns suggest a deliberate intention to shape both nature and society. Gardens throughout history were meant for exclusive interaction. By placing them next to the colonial structure, Stonehill emphasizes that colonial presence brought intentional restriction to people’s movement. Curator: Absolutely, and if we extend that interpretation, how would you say this contrasts to how indigenous inhabitants traditionally understood the land? Editor: It stands in stark opposition. Indigenous cultures often view the land as communal, fostering a reciprocal relationship, as opposed to this display of ownership and dominion. Curator: Yes, this seemingly harmless watercolor encapsulates a wealth of loaded imagery and deeper considerations of that initial cultural interaction. Editor: I’ll never look at landscape drawings the same way again. This exercise made me appreciate how the history of our treatment of land impacts societal relations to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.