drawing, painting, watercolor

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

geometric

#

cityscape

Dimensions: overall: 50.9 x 38 cm (20 1/16 x 14 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

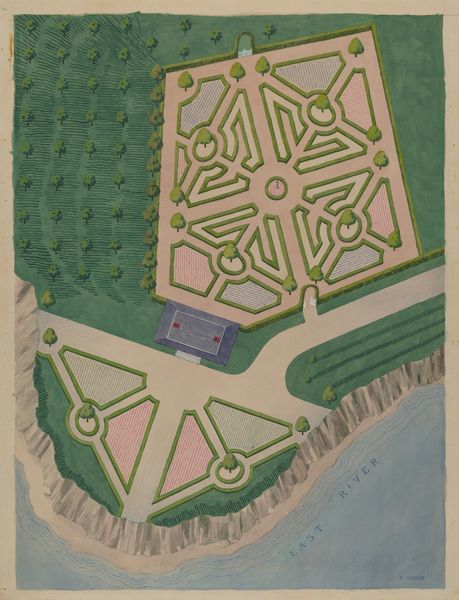

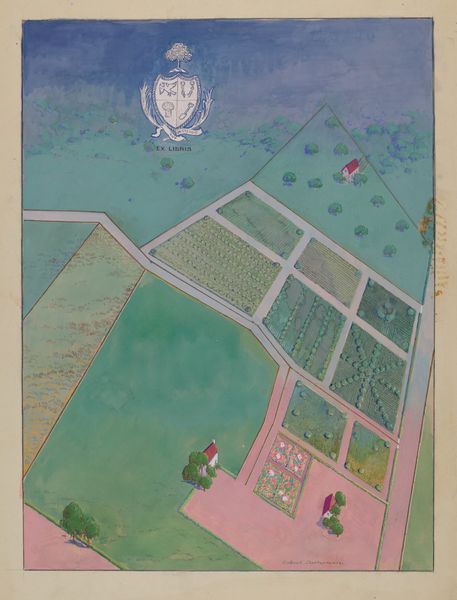

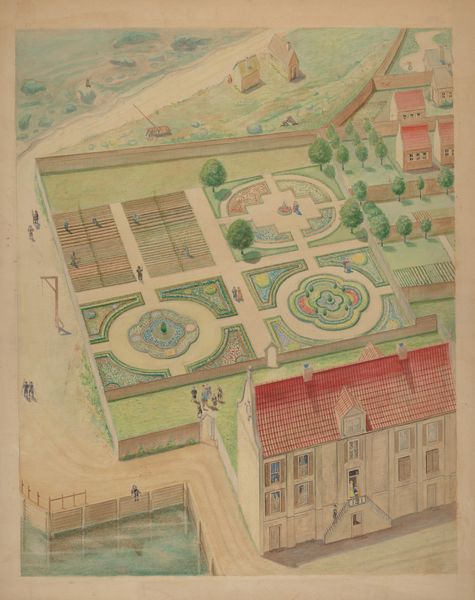

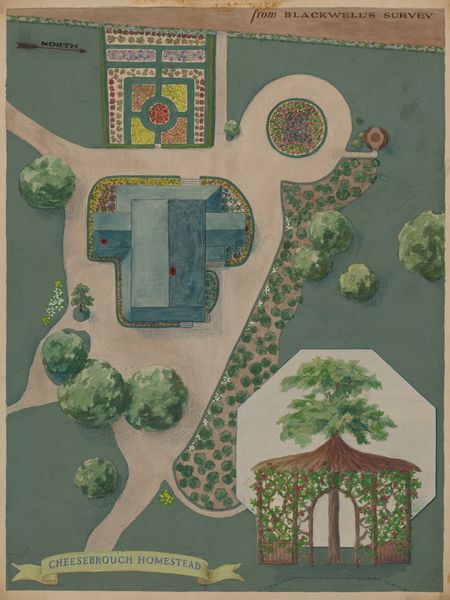

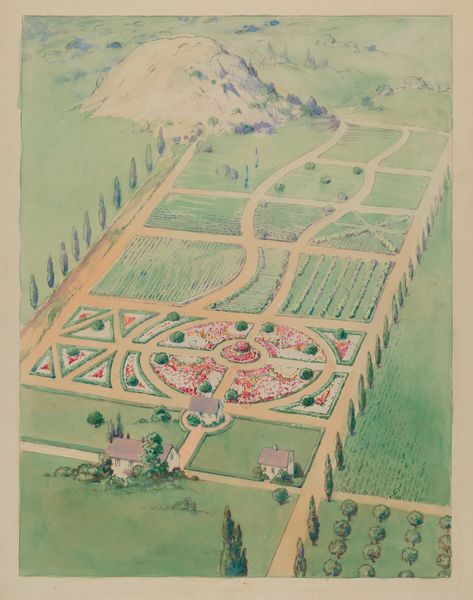

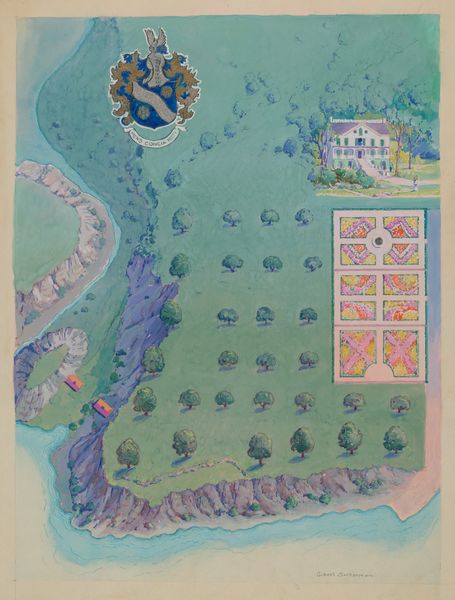

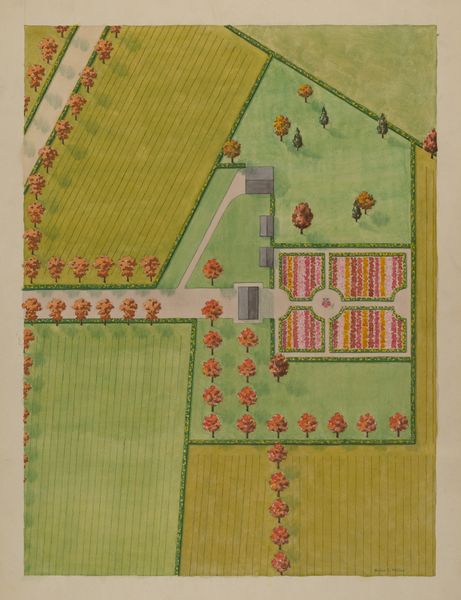

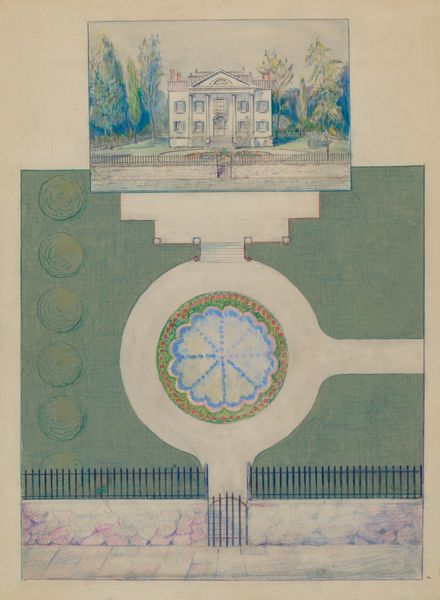

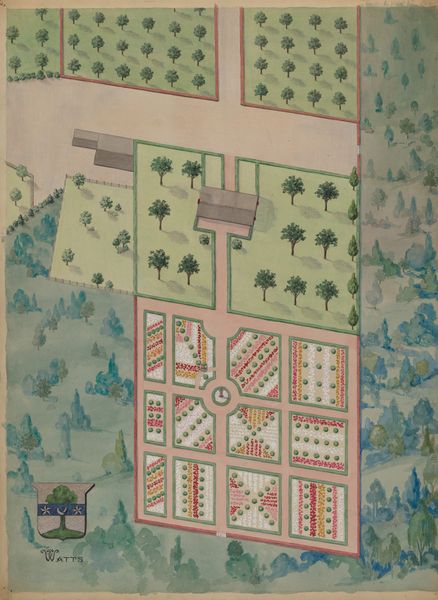

Curator: At first glance, the arrangement of these plots and patterns seems oddly charming in a rather meticulous sort of way. Editor: Indeed. We're looking at "Ranelagh Gardens," a drawing by George Stonehill, likely created around 1936. The artist employed watercolor and colored pencil to depict a birds-eye view of meticulously arranged garden plots. Curator: You know, the precise geometric layout makes me think about the labor involved in shaping the land and cultivating those gardens. I'm curious about the social hierarchy required to maintain such order and design. What does that say about urban planning during the time this work was made? Editor: Well, Ranelagh Gardens in London was indeed a fashionable public pleasure ground during the 18th century. By the time Stonehill created this drawing, the area had a long history of being shaped and reshaped by socio-political whims, echoing that history, I see here the public desire for recreation carefully designed into the urban fabric of London. Curator: I am struck by how the pale watercolors and coloured pencil almost render the physical qualities of nature like plants into simple graphic objects with neat rows. It speaks to a level of imposed control over organic materials, where even leisure is structured. It makes me question how accessible were public gardens at that period in London and who really did the labor there? Editor: Good question. These pleasure gardens, while "public," weren't necessarily equally accessible. Access was mediated by social status and, quite often, wealth, as gardens became spaces where social performances and class distinctions were visibly displayed. A watercolor drawing like this serves, then, to highlight not only an aesthetic sensibility but the economic structures that produced these carefully manufactured landscapes. Curator: So, rather than solely a picturesque landscape, we can also interpret Stonehill's rendering as an observation on the organization of labour. And perhaps even consumption since beautiful pleasure gardens attracted money and attention. Editor: Precisely. Considering how Stonehill presents this location opens an insightful dialogue about social planning, land utilization, the politics of public space, and what those spaces were intended for in 1936. Curator: It definitely gives a very different context to public spaces than maybe you realize from actually sitting within the area, today. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about both art and society is enriching and offers an unusual perspective of time, space, materiality, and place.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.