print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 425 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

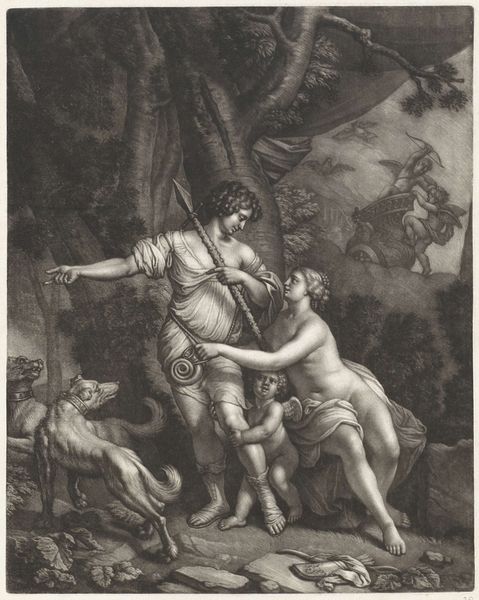

Editor: Here we have "Jupiter, Juno and Io", an engraving by Pieter van Gunst, made sometime between 1659 and 1731. The figures are very classically rendered, but there's an almost unsettling dynamic between the three. What can you tell me about the context in which this was created? Curator: It’s interesting to consider this print within the burgeoning public sphere of the 17th and 18th centuries. Prints like these democratized access to classical stories and art. While history paintings were often grand displays of power and wealth in aristocratic circles, accessible prints brought these narratives into wider circulation. Consider the implied politics of representing powerful mythological figures, especially within a growing commercial market for art. Editor: So, the average person might have been contemplating these grand mythological narratives? How do you think the depiction of these figures impacted the audience's view of power and morality? Curator: That's precisely the point! These images contributed to a collective understanding and interpretation of authority and morality. Juno, Jupiter’s wife, embodies jealousy and rage, while Jupiter… Well, the tale underscores patriarchal power, doesn't it? The naked body of Io symbolizes her vulnerability, especially relative to the power of the gods. The narrative served to either uphold or perhaps subtly critique established power structures through the familiar language of classical myth. What is your opinion on this, regarding the role of allegory? Editor: It's a potent point, considering allegory as a space for both endorsing and questioning. Seeing it as part of the public sphere complicates that binary of upholding or subverting; maybe it was a site for discussion. Thank you! Curator: Indeed, and remembering the print’s circulation invites questions: where was this displayed, who viewed it, and what dialogues did it spark in its own time? I think those are interesting questions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.