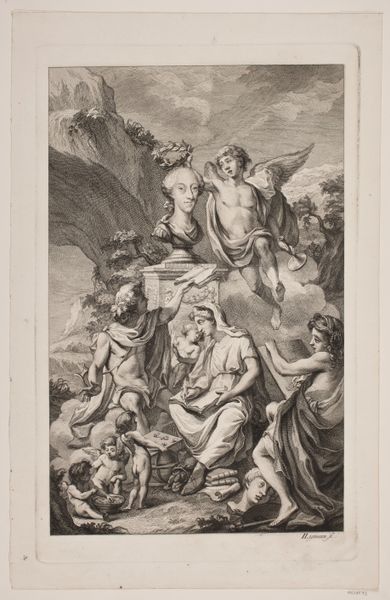

drawing, paper, engraving

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

allegory

#

sculpture

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

charcoal art

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 506 mm, width 418 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "The Three Graces by an Apple Tree," a drawing from 1783 by Jean-Baptiste Michel, currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. The scene shows three women gathering apples while a cherubic figure plucks fruit from above. What's your take on it? Editor: There's a stillness that really strikes me. A pastoral, idealized scene that feels almost…staged. Are we meant to interpret this as an engraving after a sculpture, maybe? It feels almost too…composed. Curator: Well, you're picking up on some of its Neoclassical influences, surely. The idealized forms, the allegorical nature... Neoclassicism often sought to emulate classical sculpture. Consider the textures rendered in lines—hatching, cross-hatching. See how he uses these graphic techniques to create shadow and depth, all in monochrome. Editor: I notice how the flowing drapery almost obscures their labor; like they are adorned in fabric. It speaks of consumption and production: fabrics of the day versus gathering fruit. It feels somewhat distant from real life. Curator: True. The artist uses line to convey this idyllic, almost dreamlike state. The scene, despite its realistic depiction of figures, evokes a sense of mythology. The Graces, of course, are figures representing beauty, charm, and joy. Editor: Right, they're eternally picking apples. But what kind of work is this meant to do? Is it just aesthetic delight for wealthy patrons, or is there a hidden critique embedded in the print's commodification and circulation? Was the material value meant to outlive this drawing itself? Curator: Possibly both, right? This engraving could well be reproduced and disseminated widely, potentially even coloring people’s understandings of class or gender expectations. It's easy to get lost in the idyllic representation of leisure and beauty but maybe we must read a bit deeper into it and consider its cultural product as a work in itself, you see? Editor: Absolutely. Looking at it that way enriches our understanding—it connects it to the larger material and economic reality in the eighteenth century. What seems decorative also engages with issues like patronage, and even emerging ideas around value and distribution. Curator: So, by considering it as more than just an image, but as a produced commodity with its own story, it transforms, doesn't it? Perhaps like the apples themselves: something cultivated, harvested, and consumed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.