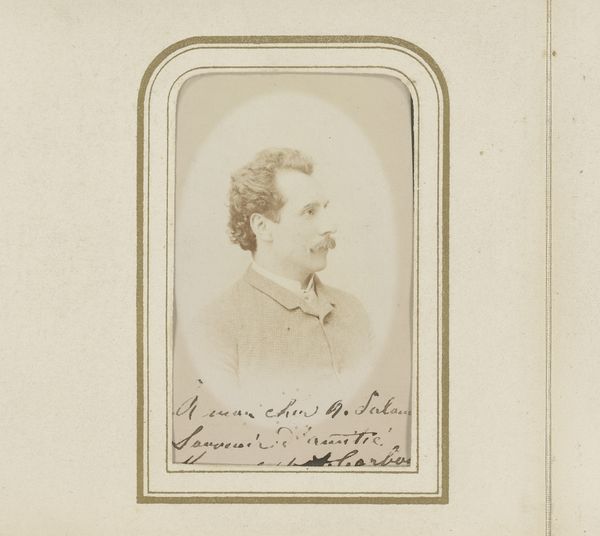

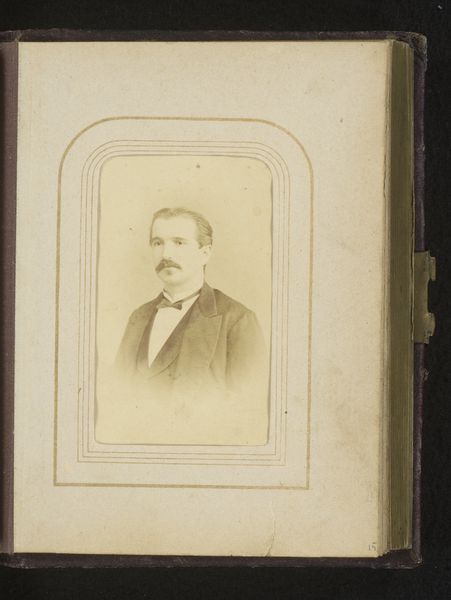

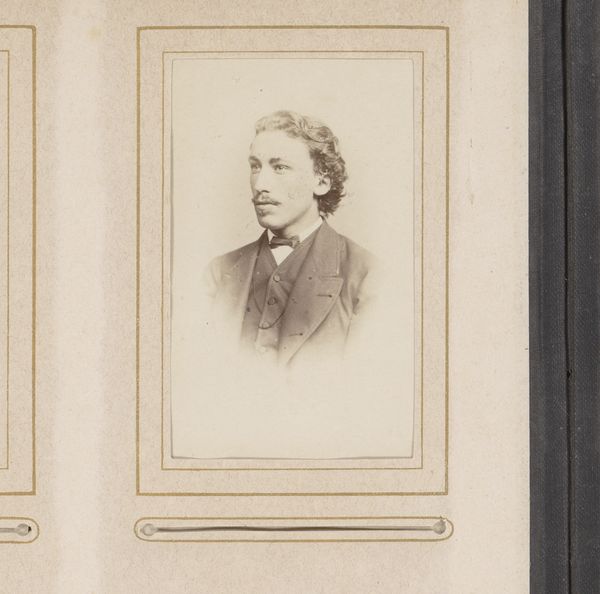

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at a photographic portrait, “Portret van een man met snor en vlinderstrik,” dating from around 1860 to 1900, likely an albumen print. It's faded and marked with age. What I find interesting is the contrast between the sitter’s carefully chosen attire and the degraded state of the print itself. What's your take on this piece? Curator: Considering it as an albumen print, we must consider its historical construction, this print being made with egg whites is fascinating. This material choice highlights the merging of domestic craft with burgeoning photographic technologies of the period. What does it reveal about the labor involved? The labor not just of the photographer, but also the unseen hands that prepared the materials? Editor: That’s a really interesting point – I hadn’t considered that. Curator: And then there's the social context. These kinds of portraits became increasingly common. It democratized representation, allowing people beyond the elite to fashion a visual identity for posterity. Think of this object as part of a rising culture of mass image production. Who was this man? How was his image consumed? Editor: So, it's less about the artistic intention and more about the entire system that created the image, from material to market. Curator: Precisely. This image exists not just as a portrait but as a node within a larger network of social, economic, and technological forces. Do we see the intersection of individual aspiration and industrialized process? Editor: That’s a valuable way to look at something that, at first glance, seems so simple and straightforward. It provides a new lense into the cultural implications of early photography and representation. Curator: Absolutely. By centering our focus on the materials and processes of its creation, we are led to question the image’s perceived value, not as art alone, but as a social and historical artifact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.