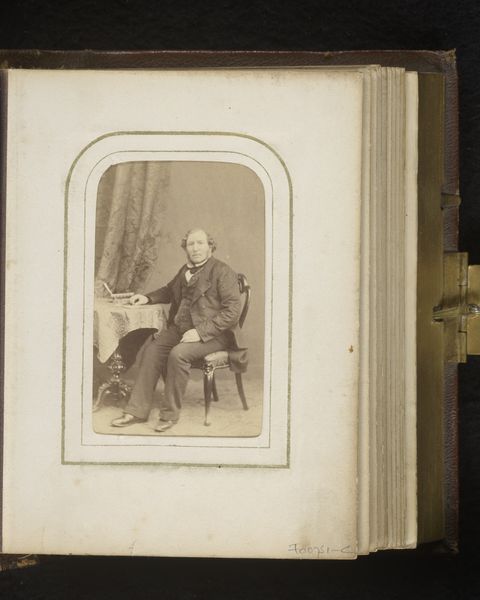

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

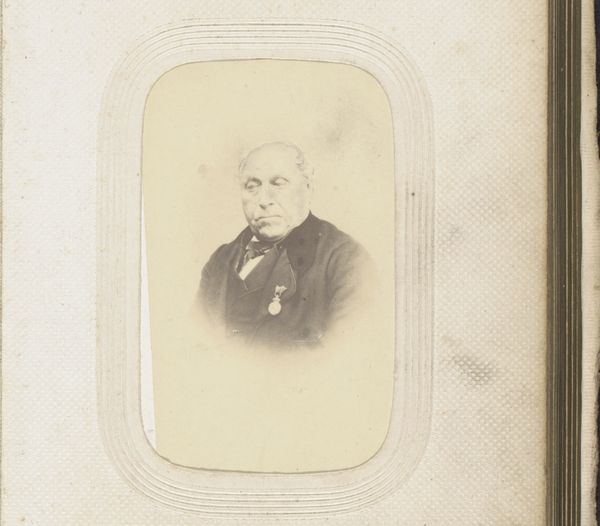

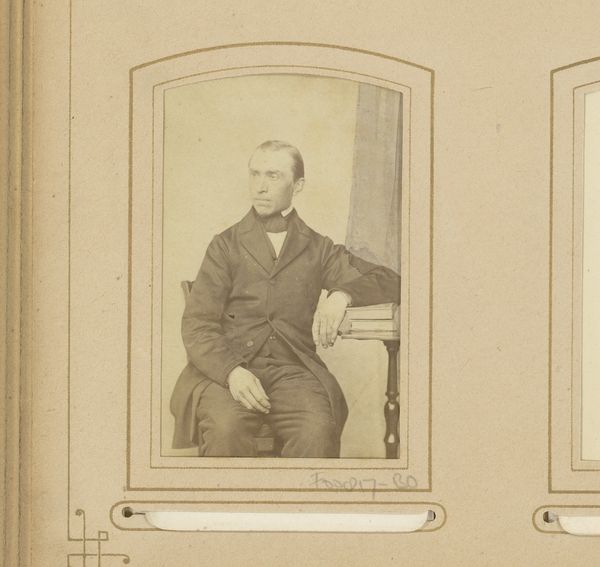

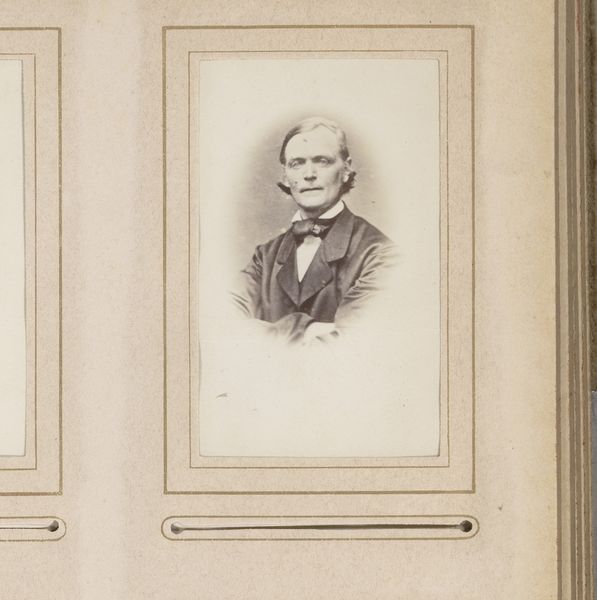

Curator: Here we have Theodor Wilhelm Schönscheidt’s "Portret van een man met bakkebaarden," dating roughly from 1855 to 1860. It’s a daguerreotype, so one of the earliest forms of photography. What are your initial impressions? Editor: It feels so haunting. The sitter's direct gaze and those formidable sideburns combined with the muted tones evoke a very serious mood, almost melancholic. I wonder what this image meant to its owner back then? Curator: Well, portraiture during this era was deeply entangled with status and identity. Daguerreotypes, despite their cost, allowed a burgeoning middle class to participate in image-making and representation. Looking at him, he's very formally dressed. Do you think there are any symbols of power or affiliation? Editor: His formal attire indeed speaks volumes about bourgeois values, perhaps aspiration. It almost looks like the photograph is housed in an ornate book or frame. Do you think that evokes certain symbolic ideas? Curator: It emphasizes the photograph as an object of display and, possibly, preservation. There’s an inherent tension—the romantic impulse to eternalize, captured through the scientific precision of early photography. A poignant convergence of art, science, and bourgeois values of the period. Was photography viewed as art or a purely scientific endeavour? Editor: An interesting debate during the rise of this new media, some embraced its ability to mimic realist painting but I think the photographic process added to its almost spiritual aura of preservation through an almost magical lens. Curator: Absolutely. And how might the intersection of class, gender, and even race—which are often absent in these seemingly straightforward portraits—play into our interpretation? Are there unspoken power dynamics in the gaze of this man? What do you see now in it? Editor: Considering that early photography largely featured white subjects of a certain status, his image inherently participates in existing social structures. Maybe a statement of defiance during turbulent years and shifts in power. Perhaps it’s also a potent reminder of who had the privilege of representation at that time. Curator: Indeed. Understanding art history also demands critically situating the subject within that broader context. Every visual element has resonance in broader political movements and gender representation, wouldn't you agree? Editor: The dialogue reminds us that objects always transcend their purely visual appeal to whisper complex messages.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.