drawing, lithograph, print, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

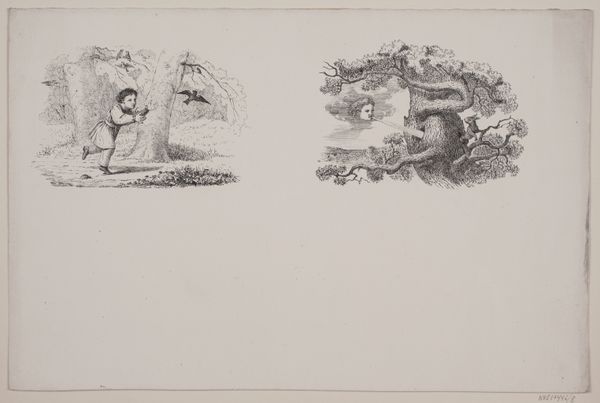

Dimensions: 277 mm (height) x 362 mm (width) (bladmaal)

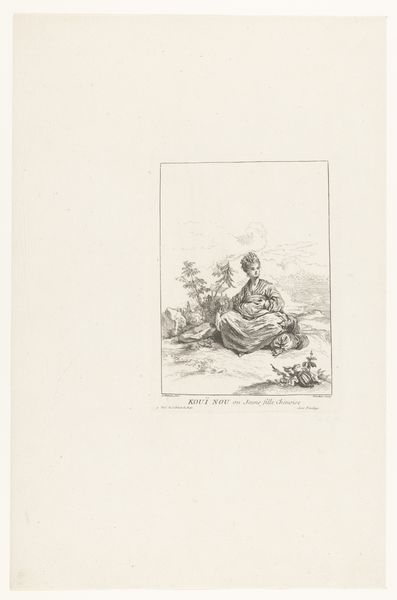

Curator: This is Adolph Kittendorff’s “Spurveungen; Lammene,” made in 1845. It is a print, specifically a lithograph and pencil drawing on paper. The sheet has two vignettes: one, a boy sitting at a table working, and another of an animal seeking shelter under stones. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the stark contrast in the depicted scenes and the humble, almost sketch-like quality of the drawing. The whole presentation feels subdued. Curator: Lithography offered artists in the 19th century a new, relatively inexpensive medium for creating multiple copies. Kittendorff’s choice to combine it with pencil allows for a more immediate, direct form of mark-making. What materials and tools might this boy be using at his table, and is this based on observing or from imagination? The combination points to the potential accessibility and reproducibility of artistic and artisan skill in society. Editor: Exactly. I read the positioning of both subjects as quite symbolic. The boy, potentially an artisan, engages in active labour, while the animal hunkers down under stones, representing, perhaps, vulnerability and a reliance on shelter—connecting to themes of survival, and protection within potentially harsh social conditions. Considering how close it is to 1848—a key year for revolts—how could the subject matter hint at the struggles and plight of the lower classes? Curator: Absolutely, and we must consider how access to reproduced imagery shapes social and political consciousness. Lithography and print enabled wider dissemination of these images, turning the artistic image into an increasingly public property. So, to return to materiality and process, lithography’s reliance on a specific kind of stone for the printing matrix—quarried, processed, shipped—speaks to global networks of extraction and consumption during this period. Editor: This makes me reflect on what ‘protection’ and ‘access’ would even look like in a broader scope: as lithographs they themselves are quite protected—do not touch—versus how ‘exposed’ and copied the drawing has become, even through art history. Curator: I think looking at both of the drawings really pushes us to consider the act of reproduction. The availability of the image speaks directly to access to subject matter for potentially wide audiences, so how would this be related to contemporary conversations about mass media, appropriation and control? Editor: The lithograph makes you contemplate material availability versus an allegorical lack of power and agency… a very interesting tension for such simple scenes. Curator: Indeed, Kittendorff has provided much for our consideration today. Editor: Absolutely, another artwork that keeps on giving.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.