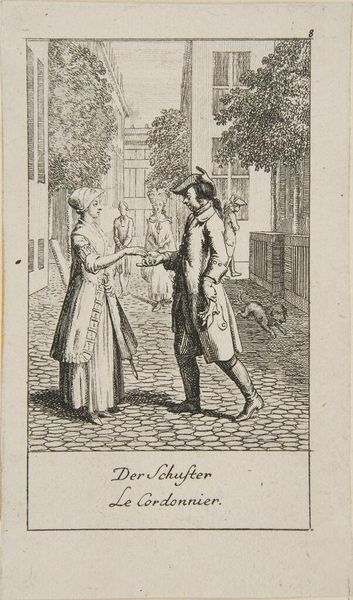

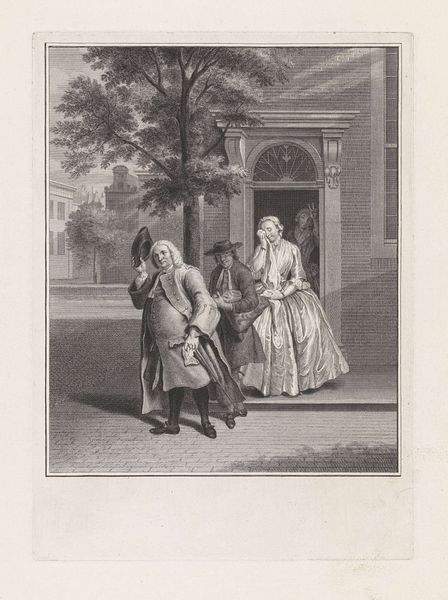

Frontispiece to Moliere's "Sganarelle, ou le Cocu Imaginaire" (The Imaginary Cuckold) 1727 - 1737

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 5 3/8 x 3 1/8 in. (13.7 x 8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: So, here we have John Vandergucht’s “Frontispiece to Moliere's 'Sganarelle, ou le Cocu Imaginaire' (The Imaginary Cuckold),” an engraving dating from the late 1720s or 30s. Editor: It's intriguing. It seems to depict a dramatic moment from a play, with these shocked figures and cramped urban setting rendered with such precise lines. What draws your eye to this particular print? Curator: Well, I'm fascinated by the materiality of it. Think about the process: the engraver, Vandergucht, translating Hogarth's original design onto a copper plate, a skilled labor turning into a multiple. These prints were essentially the mass media of their day, offering relatively affordable access to visual narratives for a growing urban audience. Consider the paper quality, the ink used – these are commodities that shaped the distribution of ideas and cultural values. Editor: So it's not just about the image itself, but how it was made and distributed? Curator: Precisely! It makes you wonder about the workshops, the social status of the engravers, and how these images were consumed. Were they displayed in homes, used to illustrate books, or traded as collectibles? This image speaks to a burgeoning commercial culture. Look at the very precise hatching marks: That reflects considerable training and practice to master that engraving. Editor: The figures' elaborate clothing also points to a specific social class consuming these prints. Curator: Absolutely. This connects to notions of status, taste, and the theatricality of everyday life. Even the dog reflects certain class considerations. And what about the gendered division of labor implied? Who was buying and reading Moliere at this time, and why? This object opens a window into a complex network of production, consumption, and social relations in the 18th century. Editor: It's fascinating to consider the layers of meaning embedded in something that at first glance just seemed like a simple illustration. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure. Now you've got a sense for understanding art as not just aesthetic object but also a material artifact, shaped by and shaping the world around it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.